Debut YA Author Crafts a Fantasy Western That Empowers Readers

In Charlotte Nicole Davis's debut YA fantasy, The Good Luck Girls, young women escape from a "welcome house" on a planet inspired by the Wild West. Davis discusses how the Old West inspired her to create an adventure story Black and brown girls can see themselves in and building a fantasy world to understand our own.

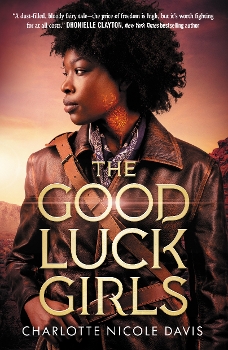

The Good Luck Girls is the first installment in debut author Charlotte Nicole Davis’s new YA fantasy series, set in an alternate world reminiscent of America’s Wild West. The young protagonists flee their incarceration as sex workers, or “Good Luck Girls,” and battle supernatural elements across an unforgiving landscape, while being pursued by deadly, misogynistic men. Each Good Luck Girl is branded with an enchanted favor, or tattoo, across her face in the form of a flower. If covered, the favor burns white hot on their face, becoming more painful the longer it’s covered. They can’t hide, but they can fight. Davis discusses the real stories of the Old West that inspired her and how she built a fantasy world to help us understand our own.

What inspired you to write this book?

Well, I grew up in Kansas City, MO, which used to be the heart of the Old West, so I was interested in writing a fantasy set in my corner of the world. The Western is also a genre that’s never felt particularly welcoming to me before, as a queer woman of color, so I wanted to write a Western about people who looked like me. It was important to me that I give Black and brown girls the chance to enjoy some of these tropes—bank robberies and bounty hunters and campfires on the trail.

|

Photo by Brett Pruitt |

Like some of the characters in this Western-inspired fantasy, you also grew up as a queer black woman in the American West. How did your background and identity influence this story?

I think more than anything, I just wanted to make sure I saw myself in this story. Historically, the American West was a very diverse time and place. There’s no reason why a story like this couldn’t be about a bunch of queer people and people of color. So I didn’t want it to feel like too much of a big deal—people aren’t discriminated against based on skin color in Arketta, and though anti-queerness does exist in this world, it’s not something we’re exposed to over the course of the story. On the other hand, we do see many examples of sexism in the book, but we also see the girls overcoming it. I wanted readers to feel empowered, to feel good about themselves.

You combined a lot of current issues (such as sex trafficking, gender inequality, misogyny, Queer theory, and representation of the LGBTQ+ community) in today’s world with a fantasy historical-type setting. Do you see these issues as universal?

I do see these as universal issues. Systems of oppression may take different forms, but I think they’re all still built very similarly, regardless of time or place. Finding those similarities helped me to build Arketta in a way that felt realistic, and it helped me decide how to weave in the fantasy elements in a way that felt organic. They’re complicated issues, and I certainly don’t pretend to know everything about them, but building this world really helped me to understand our own.

I loved that you listed all the books that helped you research and execute this novel. What is your favorite book or one that you found to be most formative to your writing style?

If I had to pick just one book, it’d probably be Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II, by Douglas A. Blackmon. It deals with America’s long history with the practice of convict leasing, which pretty directly inspires the “Reckoning” in Arketta and the creation of the dustblood caste system. But I researched a wide variety of related topics, such as chattel slavery, debt slavery, and, of course, human trafficking—especially of young girls, both historically and in the present day. It was important to me to understand how these kinds of systems of oppression work, where they come from, and how people find ways to justify them.

Welcome houses are a real part of American history that’s largely unknown. Why do you think the world has forgotten their importance?

Honestly, I think it’s because we’ve never really reckoned with our past, and it’s easier for people to forget that history rather than begin the hard work of healing. In talking about America’s history with chattel slavery, specifically, people tend to downplay the fact that the sexual trafficking of enslaved Black women was not only commonplace but systemic—the country’s entire economy depended on the rape of Black women to produce children who could in turn be enslaved. And as someone who is descended from these women who survived the unthinkable, it’s important to me that we don’t forget that history, because we’re still feeling its effects today and we’re still waiting for reparations. That’s part of the reason I called The Scab, the scab—it’s this deep wound that’s never fully been allowed to heal.

chattel slavery, specifically, people tend to downplay the fact that the sexual trafficking of enslaved Black women was not only commonplace but systemic—the country’s entire economy depended on the rape of Black women to produce children who could in turn be enslaved. And as someone who is descended from these women who survived the unthinkable, it’s important to me that we don’t forget that history, because we’re still feeling its effects today and we’re still waiting for reparations. That’s part of the reason I called The Scab, the scab—it’s this deep wound that’s never fully been allowed to heal.

Networks of good people risking their lives to help strangers is a common theme in this book. Was there a real-life situation that inspired this?

The most direct inspiration is probably the Underground Railroad, of course, but, more broadly, I was inspired by the idea of oppressed people recognizing that they’re stronger together. People in power tend to pit those below them against each other along lines of gender/race/etc., in order to prevent them from finding common ground. The characters in The Good Luck Girls have to learn to trust one another, despite what they’ve been taught all their lives, in order to survive the forces at work against them.

The supernatural elements of the book are mysterious and obviously terrifying. What’s the benefit of using supernatural elements to convey atrocities committed against the characters, specifically young women?

I kind of wanted to have my cake and eat it too with this story. I wanted to explore heavy issues like sexism and racism, which are really inseparable from both the Old West and the Western, but I also wanted this book to be, just, the most fun, because it’s so rare for Black and brown girls to get to see themselves as heroes in over-the-top action/adventure stories like this. So the fantasy elements helped me to strike that balance, because they automatically create a certain amount of distance from the real world. The cycles of violence that the vengeants and the raveners represent are very real, but the monsters aren’t.

Can you give us any hints about the next book?

Book 2 is honestly just more of everything! More of this world, more characters, more conflicts on a bigger scale. I’m excited to see where it takes me.

Melanie Leivers is the Youth Services Librarian at Burnhaven Library in Burnsville, MN, part of the Dakota County Library System. She is currently a reviewer of YA books in SLJ. She received her Master’s in Library Science from Florida State University.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!