A Matter of Facts: Teaching Climate Change

With guidance and resources, students can lead the way on climate change

|

Related articles:A Science Teacher’s Go-To Resources When Teachers Grapple with Climate Science Collaborate with Science Teachers To Share Climate Resources

|

In the red state of Wyoming, climate change can be a charged topic. That’s why Kim Parfitt avoids political stances in her honors biology and AP environmental science classes at Cheyenne Central High School when discussing the issue. “We can’t just point fingers,” she says. “We’re all a part of this.”

Over the years, however, as the effects of climate change—shifting growing and grazing seasons, altered animal migrations—have become visible in the state, Parfitt has seen more community members come around to the idea that this is both real and continuing, a perspective supported by reports emphasizing how soon our global temperature could be irreversibly altered.

Her students are increasingly drawn to the topic, too, especially those with an interest in social justice and finding solutions.

As Parfitt sees it, her number one job is to provide teens with the information they need to understand the processes behind the environmental damage.

“The challenging and the exciting part is starting with the science, because that helps with making informed decisions,” she says.

Across the nation, educators like Parfitt are working not only to build students’ understanding of each issue, but to do it in a way where kids leave class knowing they have, or could develop, the skills to shape our future environment.

The key, they say, is just to provide the facts and tools—and sometimes bring in outside experts—and then let students ask questions and draw conclusions. The emphasis on self-discovery and real-world interactions is in line with the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) being adopted at the state level, which prioritize hands-on inquiry.

Still, determining how to teach the science can be tricky. The foundation of climate change understanding lies in a range of STEM subjects, which can alienate students who have struggled with STEM in the past. Additionally, while the data shows that scientific processes are changing our planet because of social, political, and economic choices, those factors can be complicated to tease apart in class.

Then there’s the question students inevitably ask: Now what? What are we supposed to do with the information about how humans are damaging our environment?

|

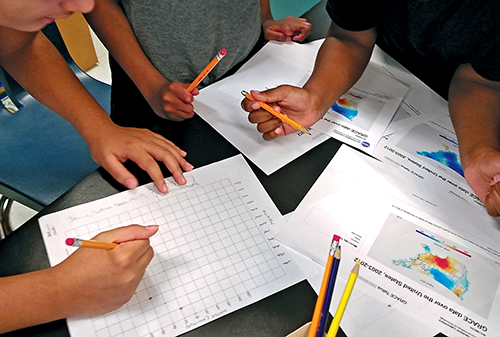

Students at Desert Ridge Middle School in Albuquerque, NM,

|

Making STEM appealing

Not every student in Parfitt’s classes is enamored with the subject—some are there because it’s an honors course, or because their parents signed them up. To engage them, Parfitt develops STEM lessons that play to a range of interests and strengths, such as design or project management. That way, students can find an avenue into the math- or science-based material that appeals to them.

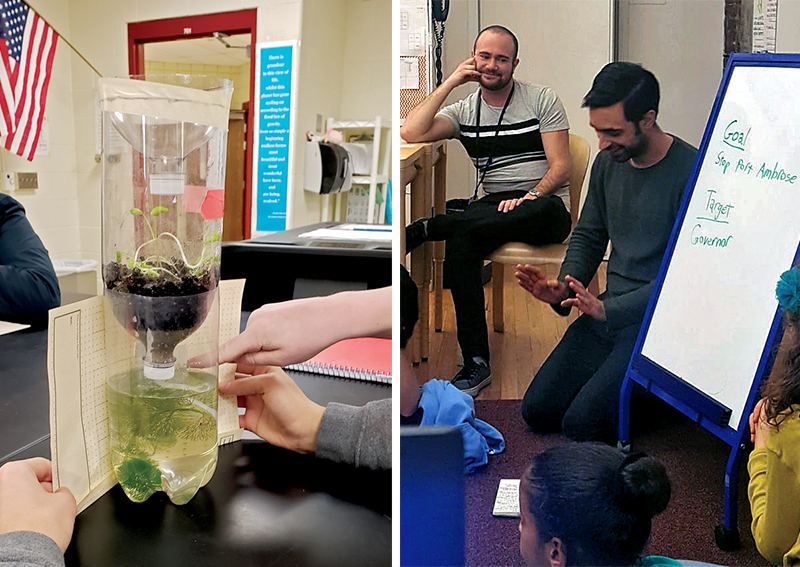

One way to touch on multiple aptitudes is through group projects. Each year, Parfitt’s honors biology students build “bio bottles”—self-contained ecosystems in empty soda bottles. An aquatic habitat, complete with tiny fish at the bottom, connects via cotton string to a dirt and pill bug environment above.

Building the model, monitoring growth, and reporting how the systems interact requires engineering, documentation, data analysis, and design skills—all while teaching students about how ecosystems are interconnected. This is essential information for understanding how climate change alters natural ecosystems. While every student will have to do some math or graph-based work, Parfitt says, “they can play a role that makes them feel some efficacy.”

Many educators turn to NASA for their teaching tools. At NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, CA, senior education specialist Ota Lutz provides climate change science lessons that entice kids with all kinds of subject angles. Lutz works in the lab’s elementary education group and writes publicly available lessons based on JPL’s work and data.

Many students who are initially drawn to JPL’s space exploration research are happy tackling math problems to learn how, for example, the agency tracks wildfires with remote sensing. “We got lucky. Kids love space,” says Lutz.

For those who shy away from science, Lutz and her team write lessons that ask students to make relevant art, write poetry, or play Ocean World, a game of catch that shows students just how much of our Earth is covered in water. “If there’s an opportunity to do something they’re already interested in or have prior knowledge about, students are more willing to learn,” she says.

|

Students graph real data from NASA’s Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment satellite, which tracks water mass changes in the United States.Photo courtesy of NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory |

Even when the lesson plan is mostly hard numbers, Lutz and her department keep it activity-based: That approach often shows kids they are capable, even if they didn’t think they were. Tackling the math and science can also prove to students that they can accomplish seemingly intimidating work. Presented with a challenge, “a lot of kids go, ‘oh, that’s scary!’” says Lutz. “That’s such a seminal moment. We can let them walk away…or we give them stuff at their level right now, and help them through it so they learn they are capable of doing things that [seem] out of reach.”

Other educators like Lynn Cole believe that some kids have an easier time connecting to STEM topics in less formal environments. Cole is the interactive exhibit supervisor at the Children’s Library Discovery Center at the Queens (NY) Central Library. Locals who attend her Saturday science sessions—which almost always include a climate change section—practice new vocabulary and participate in activities that link to the main lesson.

In January 2019, for example, the kids made visors while learning how climate change may increase the risk of sun damage. Because the activity happens at the library, outside of the pressures of homework or a class they might not like, “we hope that then people feel more free to let their minds latch onto things,” says Cole.

After the facts, the questions

Once students are engaged and participating in Parfitt’s classroom, the next step is to back away from providing all the information. She lets them lead the discovery process by asking and answering questions.

If the lesson is about the impact of wildfires, the class will start with a brainstorm session that raises queries, such as how burning changes watersheds or smoke changes air quality. Parfitt knows where the conversation will wind up—questions are predictable, and there are particular technical terms and systems AP students need to know for their test. But this tactic lets students uncover patterns themselves.

Lutz and her colleagues at JPL use the self-discovery approach as well. As a federally funded employee writing federal science lessons, Lutz stops short of providing conclusions; the lessons are mostly information and a bunch of prompt questions. “As much as I have my interpretations, I’d rather provide enough data and lessons to have students answer their own questions,” she says. Besides, asking students to draw conclusions means they have to return to the data to justify their thought process, another valuable skill.

Meet the climate pros

Once students have a solid understanding of the underlying science, educators like Turtle Haste, a science teacher at Desert Ridge Middle School in Albuquerque, NM, start to explain how policy and social dynamics influence the biological processes changing our environment. “That’s the hardest part to engage,” she says.

Sometimes, Haste will turn to social science teachers for a collaborative lesson. If her class has just learned, for example, that polar bears are losing their habitat, then other teachers can guide them through where that territory lies, and who owns it.

She also introduces students to professionals who use climate science knowledge every day. In 2005, Haste contacted the United States Antarctic Program for help in fielding student questions. Since then, she’s kept in touch. Recently, an oceanographer investigating the carbon sink potential of the Southern Ocean in Antarctica came by to show students two data-gathering floats that bore the name of their school. He answered questions and told Haste’s seventh graders that they could see the data that the two floats record.

Parfitt connects her students with professionals through an environmental science book club. She invites members of several fields, from ranchers to state legislators, to pick a popular science book that relates to their work. The choices have ranged from Gary Ferguson’s Land on Fire, about fighting western fires, to David Quammen’s Yellowstone: A Journey Through America’s Wild Heart, focusing on the national park’s ecosystem and the people working to protect it.

The group gets together in the glass-walled school library to talk about the science, policy, and reality of working in their profession. “Students can see this is real-life stuff,” says Parfitt. Other students passing by the library see their classmates hold meaningful conversations with professionals.

In the library at New York City’s Corlears School, librarian Kyle Lukoff, who helps coordinate the social justice program for first through fifth graders, brought in a climate activist. The young students were primed for this conversation, Lukoff says. Activist Patrick Robbins spoke to the students about organizing and leading protests against an offshore natural gas facility in New York. In 45 minutes, Robbins went from making sure the students understood the basics of climate change to talking with them about how people act collectively to mitigate its impact.

It was more of a conversation than a lecture, and Robbins encouraged students when they spoke up, keeping enthusiasm high, Lukoff says. They got the sense that those working in environmental professions are regular people. “Activism isn’t just names they read in headlines—some of the people doing this work are friends with their librarian,” says Lukoff. “It’s just people having a job, and it’s not out of their reach or skill set.”

|

“Bio bottles” in Parfitt’s classroom demonstrate codependent ecosystems;

|

Beyond doom and gloom

Adopting sustainable practices and engaging with the status quo are essential to the learning process, Haste believes. When students act on what they learn in class, it’s much more than a feel-good project.

Still, she has found it difficult to get administrators on board when, for example, students launch and run recycling programs. Haste expects that to change now that her state has adopted the NGSS. Because the guidelines are inquiry and project-based, there’s an implication that students will learn to follow through on their learning with real-world applications.

If students don’t initiate their own programs, case studies can have a deep impact. While Ama Ehrmann was teaching a seventh grade science class at Memphis (TN) Rise Academy, her supervisor, Rebecca Olivarez, suggested she teach a climate change lesson that culminated in an advocacy project. Ehrmann devoted a day to the science of four environmental problems—acid rain, fossil fuels, ocean pollution, and deforestation—and then had students create a presentation for the hypothetical Memphis Financial Committee on law and policy adjustments to propose solutions for these problems.

Each student explained how the city’s choices were compounding an environmental issue and how it could reallocate resources into less harmful practices. One student focusing on air pollution explored electric cars, says Ehrmann, investigating the different companies and how to make the cars more cost-effective. Though it can be hard to link the environmental problems students see to corporate choices, these activities let students demonstrate to an audience how policy impacts ecosystems. “Going from the paper to the project so students can see the effect of a positive change is necessary,” Ehrmann says.

Maintaining positivity—welcoming lesson plans, introducing students to real-life environmental professionals, and creating action plans—is paramount when exploring these issues. “The hard part is getting them beyond doom and gloom,” says Haste, especially since it will take society decades to repair some of the damage that’s been done.

To build a support network, Haste shares ideas with like-minded teachers. She has also tapped into resources she trusts to help her build quality lessons. National Public Radio’s Science Friday, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the teacher-led PolarTREC initiative provide her with great plans, and she turns to her school librarian to source up-to-date and ELL-friendly climate information. When she gets going with a lesson, the enthusiasm tends to spread. “I get all excited about a project, and the next thing you know, the math teacher is excited too, and we’re working together.”

Even if that enthusiasm isn’t reflected in students’ faces, that doesn’t mean the lessons are forgotten when they leave the room. Parfitt has heard parents say that their kid has come home and convinced the family to improve their recycling habits. A student who was quiet in class told her at the end of the year that the AP environmental science class was the most important one she’s ever taken.

“There is never a linear effect with teaching, and things can surprise you,” she says. “These kids are powerful.”

Leslie Nemo is a freelance science journalist based in New York City.

|

Libraries step up: In January 2019, the American Library Association (ALA) voted to adopt sustainability to its Core Values in Librarianship. This followed an eight-month study by an ALA task force that provided 52 recommendations for ways that libraries can help communities thrive. Full report |

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!