2018 School Spending Survey Report

Cherie Dimaline On Erasure, the Power of Story, and “The Marrow Thieves”

The acclaimed Cherie Dimaline chats with SLJ about her YA debut, the importance of language, the colonization of Native peoples, and how teens are the hope for the world's future.

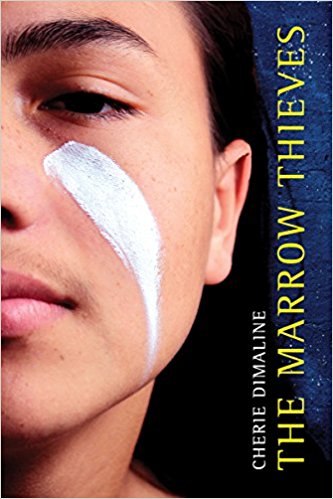

Photo courtesy of Dancing Cat Bks

Cherie Dimaline is new to the YA world, but in a few short months, she has been named the winner of one of the most important Canadian author awards and a finalist in the prestigious Kirkus prize. Her first novel for teens, The Marrow Thieves (Dancing Cat Bks., Sept. 1, 2017), focuses on the survival of a group of Indigenous youth in a postapocalyptic world where white people no longer dream and Native people are being hunted for their bone marrow because of its medicinal ability. This coming-of-age story centers on Frenchie, a teen who is searching for his captured brother. Dimaline chats with SLJ about the importance of language and books, the colonization of Native peoples, and how teens are the hope for the world's future. Can you tell us a little bit about your path to publication? As far back as I can remember I’ve wanted to be a writer. Even before I could physically write, the idea of creating story seemed like magic. My life was unpredictable and expansive and I found myself working jobs like “magician’s assistant” and “museum curator” and “mom” before I finally found employment with words. And even then, it was as an editor at a women’s magazine I had never read before the interview. Finally, in 2016, faced with the impending loss of my grandmother who raised me with traditional stories, I hunkered down and wrote my first book, a collection of short stories called Red Rooms. I was able to tell my grandmother the book was being published before she died, fulfilling a promise I made years before. Two more books came after Red Rooms; the novel The Girl Who Grew a Galaxy and another collection of stories, A Gentle Habit. And this year, my first YA novel. What inspired you to write The Marrow Thieves? I was asked to contribute to an anthology of Indigenous science fiction and speculative stories. At first, I thought it was a strange mix, but then really, who better to write a story about people surviving an apocalypse than a people who already had? So I put together two different ideas: that Indigenous people’s survival has been based, in part, on the ability to keep dreaming/hoping and using story to walk culture forward, and the understanding that cultural survival is as imperative as physical survival, and in fact, is intertwined. I also really needed Indigenous youth to see themselves in the future, and not just holding on by the skin of their teeth kind of surviving, but being heroes and leaders. And I wanted all youth to be collectively drawn to the conclusion that they would never let something as horrible as residential schools (which existed in Canada until 1996) ever happen again. Congrats on winning the Governor General’s Literary Award and being a Kirkus Prize finalist! How did you react when you first found out about these great honors? I was absolutely knocked-on-my-butt shocked when I heard about both the Kirkus and the Governor General’s Award, especially when I saw the caliber of books I had been nominated alongside of. I never expected to have such a wide readership for this book, or to be recognized with such esteemed nominations. I am very cognizant that when an Indigenous writer or text gets put into the spotlight, however briefly, that it is a win for our entire community and an opportunity for other stories, issues, and writers to come through, so I am enormously grateful to be the one holding the door open right now. The history of colonization and genocide of the First Nations people is intertwined so seamlessly with the world-building in this postapocalyptic world. How did you map these two themes within the narrative? I very strongly believe that with the current state of the world, one of the best options we have as the human race is to start globally valuing the traditional and ecological knowledges that are held by the original inhabitants of the land. This is not to say that everyone doesn’t have a place, it’s just that for too long Indigenous knowledge has been considered archaic or unnecessary and not taken into consideration. It’s become quite obvious that the western systems are failing us now. The earth is changing, and not for the better, no matter who wants to deny it. Wouldn’t you want to learn the best way to bring us back to living in balance and prolonging existence by people who understood their specific lands the best? People whose languages are shaped after the waters, hills, and features of their landscapes? I started with this hopeful narrative of a triumphant return to Indigenous Traditional Knowledge as the saving grace for us all. And then I remembered what happened the first time we welcomed newcomers and tried to share, and all the horrific steps that brought us into the schools and away from our teachings. And I thought, well, I have to talk about that possibility, too. We need to discuss our shared history so that we can ensure it doesn’t repeat. The Marrow Thieves brings us through the potential of a repeated history: migrations without consideration of original lands and laws, loss of culture, commodification of spiritual practices, and the fight to survive it all. It is a YA book because it needs to be for the youth, so they can love these characters and want them to persevere and then realize that they can be the world-builders that make sure this never happens. Can you tell us more about your writing process? I wish I had a more romantic or even organized process. I spoke with an award-winning nonfiction writer last week who talked about “office hours” and working her writing as a nine-to-five job, and I was so envious. Really, I write sporadically, almost constantly, and in a haphazard fashion. Last month I started a new novel on the back of an airplane barf bag while flying home from British Columbia. But I do read all the time, which is crucial, and I do prioritize writing over everything else, including sleep, with maybe the exception of my kids—maybe. Who was your favorite character to write? Hands down Frenchie. With him I was able to be immediate and intimate and to feel things like first love and jealousy and rage without apology. I rarely got out of his head, but luckily, it was a fun place to be. The language is this book is so rich and lyrical and the loss of language is an important undercurrent in the book. Why did you think it was important to include this aspect? There has been such a campaign of erasure where First Nations culture (and people) are concerned. It was illegal for us to sing our songs and carry out our ceremonies until 1950. Children were beaten and abused for even attempting to speak their languages in the residential schools. But somehow, we still have speakers and we still sing our songs and we still have ceremony. Our ancestors fought with their lives for us to inherit these things knowing that they are central to our existence. I wanted to honor their struggle and mirror the lengths to which they went to in order to pass these gifts on to us. I purposely made the Indigenous language in this book, when it is used, rudimentary to show that even when you use a word or a phrase as a beginner, as long as you are fighting for its survival, language is powerful, that it encompasses an ideology and life that is worth protecting at all costs. There is so much loss and sacrifice in this novel. Why do you think this will resonate with teens? I can’t imagine being a teen today. On the one hand, they are faced with full exposure, immediate judgment, and a society that is obsessed with dragging people out into the light and pulling them apart piece by piece through social media. On the other hand, they live in tumultuous times where our governments are unbalanced, the earth is starting to react to pollution and corruption, and critical decisions that will directly impact their futures are playing out right in front of them. I think this is the generation who has to bring everyone back to their senses, and they are starting to come into this now. In Indigenous communities, we are seeing more and more youth not only getting the highest levels of education in the school system, but who are returning to ceremonies, learning their languages, and challenging the status quo. All youth are sacrificing their carefree years to learn, to build, to take action. They are learning hard histories that their predecessors buried. And they are running out in front to take the lead. In this way, I hope they see themselves in Frenchie and his family. Not just the struggle, but the joy and the life beyond mere existence. I hope they see themselves as leaders and heroes, grounded in tradition but moving forward with the strength of new knowledge as well. What advice would you give young people who aspire to be authors? Do not let anyone discourage you. Yes, it is hard, and yes, there are obstacles, but that’s not any different than anything else worth doing. I heard a lot of “pick a career with more security or certainty,” and that made me put off prioritizing my writing for a lot of years. But I think if something is worth doing and you are willing to put all your passion and effort into it, than do it. Read voraciously, submit your writing to literary magazines, read at open mics, talk to other writers, and don’t waver in your commitment to your stories; they need you as much as you need them. What are you working on next? A few things. This is how it always goes with me—I’m a bit scattered between projects at the beginning, and then one really sinks its teeth in and pulls me down its path, kicking, and screaming. One is the story of a young girl who lives with her grandmother beside an abandoned mental health facility that may or may not still be inhabited. The other is based on the traditional stories my grandmother told me about a creature called the “rogarou,” a large black dog who walks on its hind legs and sometimes looks like a neighbor or loved one.

The history of colonization and genocide of the First Nations people is intertwined so seamlessly with the world-building in this postapocalyptic world. How did you map these two themes within the narrative? I very strongly believe that with the current state of the world, one of the best options we have as the human race is to start globally valuing the traditional and ecological knowledges that are held by the original inhabitants of the land. This is not to say that everyone doesn’t have a place, it’s just that for too long Indigenous knowledge has been considered archaic or unnecessary and not taken into consideration. It’s become quite obvious that the western systems are failing us now. The earth is changing, and not for the better, no matter who wants to deny it. Wouldn’t you want to learn the best way to bring us back to living in balance and prolonging existence by people who understood their specific lands the best? People whose languages are shaped after the waters, hills, and features of their landscapes? I started with this hopeful narrative of a triumphant return to Indigenous Traditional Knowledge as the saving grace for us all. And then I remembered what happened the first time we welcomed newcomers and tried to share, and all the horrific steps that brought us into the schools and away from our teachings. And I thought, well, I have to talk about that possibility, too. We need to discuss our shared history so that we can ensure it doesn’t repeat. The Marrow Thieves brings us through the potential of a repeated history: migrations without consideration of original lands and laws, loss of culture, commodification of spiritual practices, and the fight to survive it all. It is a YA book because it needs to be for the youth, so they can love these characters and want them to persevere and then realize that they can be the world-builders that make sure this never happens. Can you tell us more about your writing process? I wish I had a more romantic or even organized process. I spoke with an award-winning nonfiction writer last week who talked about “office hours” and working her writing as a nine-to-five job, and I was so envious. Really, I write sporadically, almost constantly, and in a haphazard fashion. Last month I started a new novel on the back of an airplane barf bag while flying home from British Columbia. But I do read all the time, which is crucial, and I do prioritize writing over everything else, including sleep, with maybe the exception of my kids—maybe. Who was your favorite character to write? Hands down Frenchie. With him I was able to be immediate and intimate and to feel things like first love and jealousy and rage without apology. I rarely got out of his head, but luckily, it was a fun place to be. The language is this book is so rich and lyrical and the loss of language is an important undercurrent in the book. Why did you think it was important to include this aspect? There has been such a campaign of erasure where First Nations culture (and people) are concerned. It was illegal for us to sing our songs and carry out our ceremonies until 1950. Children were beaten and abused for even attempting to speak their languages in the residential schools. But somehow, we still have speakers and we still sing our songs and we still have ceremony. Our ancestors fought with their lives for us to inherit these things knowing that they are central to our existence. I wanted to honor their struggle and mirror the lengths to which they went to in order to pass these gifts on to us. I purposely made the Indigenous language in this book, when it is used, rudimentary to show that even when you use a word or a phrase as a beginner, as long as you are fighting for its survival, language is powerful, that it encompasses an ideology and life that is worth protecting at all costs. There is so much loss and sacrifice in this novel. Why do you think this will resonate with teens? I can’t imagine being a teen today. On the one hand, they are faced with full exposure, immediate judgment, and a society that is obsessed with dragging people out into the light and pulling them apart piece by piece through social media. On the other hand, they live in tumultuous times where our governments are unbalanced, the earth is starting to react to pollution and corruption, and critical decisions that will directly impact their futures are playing out right in front of them. I think this is the generation who has to bring everyone back to their senses, and they are starting to come into this now. In Indigenous communities, we are seeing more and more youth not only getting the highest levels of education in the school system, but who are returning to ceremonies, learning their languages, and challenging the status quo. All youth are sacrificing their carefree years to learn, to build, to take action. They are learning hard histories that their predecessors buried. And they are running out in front to take the lead. In this way, I hope they see themselves in Frenchie and his family. Not just the struggle, but the joy and the life beyond mere existence. I hope they see themselves as leaders and heroes, grounded in tradition but moving forward with the strength of new knowledge as well. What advice would you give young people who aspire to be authors? Do not let anyone discourage you. Yes, it is hard, and yes, there are obstacles, but that’s not any different than anything else worth doing. I heard a lot of “pick a career with more security or certainty,” and that made me put off prioritizing my writing for a lot of years. But I think if something is worth doing and you are willing to put all your passion and effort into it, than do it. Read voraciously, submit your writing to literary magazines, read at open mics, talk to other writers, and don’t waver in your commitment to your stories; they need you as much as you need them. What are you working on next? A few things. This is how it always goes with me—I’m a bit scattered between projects at the beginning, and then one really sinks its teeth in and pulls me down its path, kicking, and screaming. One is the story of a young girl who lives with her grandmother beside an abandoned mental health facility that may or may not still be inhabited. The other is based on the traditional stories my grandmother told me about a creature called the “rogarou,” a large black dog who walks on its hind legs and sometimes looks like a neighbor or loved one. RELATED

RECOMMENDED

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!