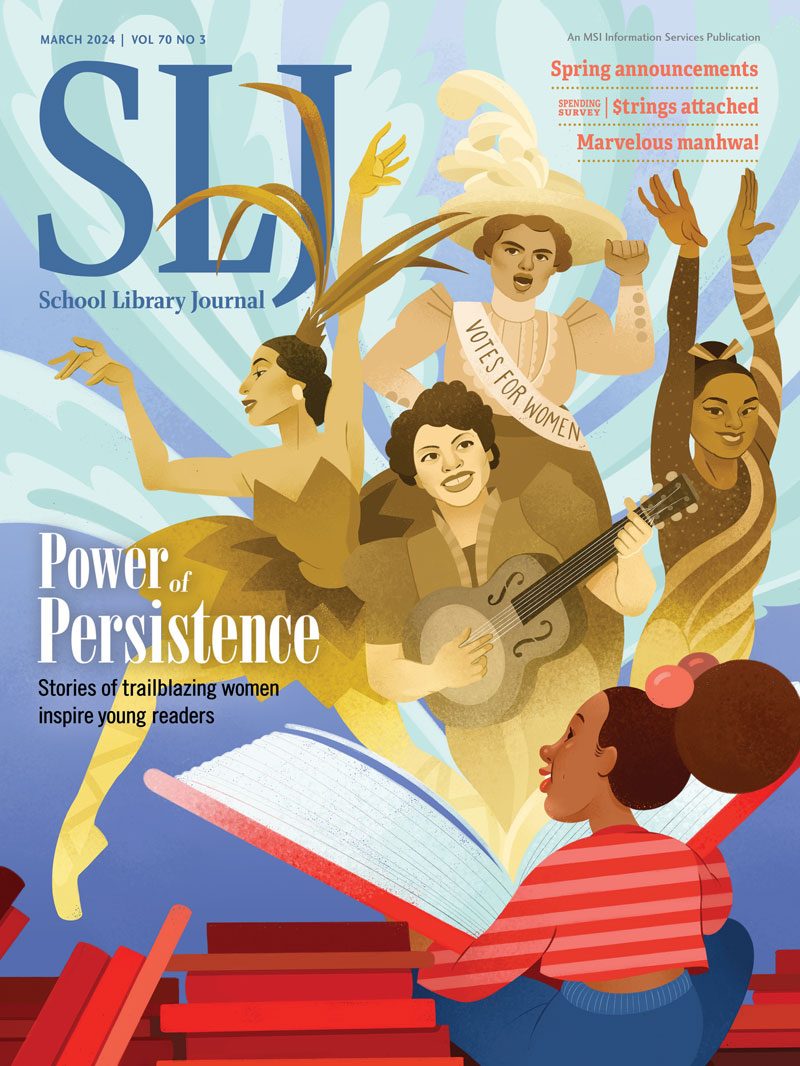

Power of Persistence: Publishers Embrace Women’s History, Inspiring Young Readers

It’s a good moment for new women’s history books—and also a good time for librarians to cull outdated titles.

|

Illustration and SLJ March cover by Caitlin Kuhwald |

In the 2023 blockbuster movie Barbie, Gloria, a frustrated mother and Mattel employee played by America Ferrera, delivers a monologue about society’s impossible expectations of women.

“We have to always be extraordinary, but somehow we’re always

doing it wrong. . . . And it turns out in fact that not only are you doing

everything wrong, but also everything is your fault.”

Related Reading: |

Barbie had earned more than $1.38 billion worldwide by September 2023 and is the highest-grossing movie directed by a woman. It garnered rave reviews from moviegoers and professional critics but also provoked impassioned reactions from those who didn’t like the film’s feminist message.

Historically, representations of feminism and strong, independent women in art and culture, including in the pages of children’s books, have inspired fervent reactions. Researchers from different academic fields have been studying women’s representation in children’s literature (e.g., how often they are depicted in illustrations and/or text) for decades. The big-picture view from these studies: over time, women have been underrepresented in children’s literature. Furthermore, much of the representation that did exist has tended to perpetuate sexist ideas.

In 1970, feminist writer Elizabeth Fisher affirmed that conundrum with this observation: “[Books] show some of the methods by which children are indoctrinated at an early age with stereotypes about male activity and female passivity, male involvement with things, women’s with emotions, male dominance and female subordination,” Fisher wrote in a New York Times column.

Since then, kid lit portrayals of women and diverse populations have vastly improved. Newer titles are better at portraying complex or intersectional identities, as Tessa Michaelson Schmidt, director of the Cooperative Children’s Book Center at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, recently noted; they’re of a “higher quality” and better at capturing authentic human experiences. It’s a good moment for women’s history books and also a good time for librarians to reconsider titles that are outdated in ways they might not have even considered.

Defining ‘‘women’s history’’

communities and became nationally recognized in 1982 after years of lobbying by women’s groups. Several years and additional petitioning efforts later, Congress passed “Public Law 100-9” in 1987 designating March as Women’s History Month. And what does “women’s history” mean, exactly? According to the National Women’s History Museum, an online institution founded in 1996, “Women’s history contextualizes women within the social, political, legal, and cultural systems of their times. History that does not acknowledge women’s situations as well as their activities and accomplishments is, by definition, not a full history. At the same time, women’s history is not merely the addition of women’s contributions to the standard history timeline. Women’s history is not just add women and stir.” |

Nevertheless

For proof of positive trending, witness the instant success and staying power of “She Persisted,” the women’s biography series from Penguin. Former first daughter Chelsea Clinton launched the series in 2017 with the publication of She Persisted Around the World: 13 Women Who Changed History. The picture book’s enthusiastic reception inspired Clinton and her editor, Talia Benamy, to create more “She Persisted” titles for more ages.

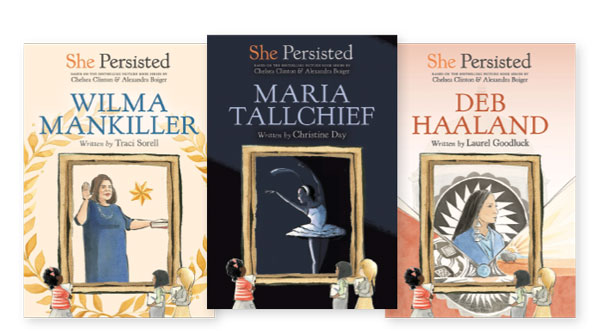

There are now more than 25 “She Persisted” titles, and award-winning authors such as Meg Medina, Rita Williams-Garcia, and Deborah Heiligman have written or co-written “She Persisted” chapter books for young readers about women like Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor, Olympic track and field star Florence Griffith Joyner, and labor activist Clara Lemlich, respectively. Recently three “She Persisted” chapter books—She Persisted: Maria Tallchief, She Persisted: Wilma Mankiller, and She Persisted: Deb Haaland—were 2024 American Indian Youth Literature Awards middle grade honor titles.

The “She Persisted” titles stay true to an activism ethos with their format—the chapter books conclude with lists of ways young readers can become activists—and with their storylines, which start with the subjects as children and chronicle failures and trying again.

“I think the idea of not giving up is so relevant and so resonant and such an important message for kids to see,” Benamy says.

Rebels rising

The idea of exposing young girls to stories of strong, inspiring women motivated Francesca Cavallo and Elena Favilli, in 2016, to crowd-fund the publication of Good Night Stories for Rebel Girls: 100 Tales of Extraordinary Women, a collection of mini biographies featuring women such as Egyptian ruler Cleopatra and Olympic gymnast Simone Biles, for ages six and up. The record-breaking success of their funding campaign (Cavallo and Favilli ultimately raised more than $1 million and sold more than 370,000 copies of their first book, according to Circana Bookscan), and their belief that there weren’t enough children’s books about history-making women and their accomplishments, convinced the pair to publish more “Rebel” stories.

Today, Rebel Girls is a global multimedia company with more than 40 books, an award-winning app, a podcast, and more. Its employees no longer rely on funding campaigns to keep afloat; Rebel Girls has raised millions for future ventures and counts Penguin Random House, Common Sense Growth, and Nike among its investors.

“We love what we do, and we love and are inspired by the audience that we serve,” says Rebel Girls CEO Jes Wolfe.

Seen but not heard from enough

A recent report on the dearth of women in U.S. social studies standards showed that women’s representation is nowhere near what it should be in social studies classrooms; in addition, a 2023 AI-based study on race and gender in children’s books showed that women’s inclusion has fallen short over the years.

In 2017, researchers with the National Women’s History Museum analyzed states’ K–12 social studies standards to identify areas where educators might need more resources on women’s history. The report and analysis found that “women’s experiences and stories are not well integrated into U.S. state history standards…This implies that women’s history is not important.”

And in 2023, researchers at the University of Chicago used cutting-edge technology to analyze representation in award-winning children’s books’ texts and images. Economist Anjali Adukia and her team developed an AI application built on existing face analysis software and natural language processing tools and trained it to detect faces, determine skin color, and predict depictions of gender, race, and ages. The tool allowed them to quantify representation in a new way and enabled researchers to standardize processes and eliminate the human biases said to sneak into many AI applications.

The study focused on over 1,000 books for children 14 and under that had won or been honored by the Association for Library Service to Children beginning in 1923. Prizes ranged from the Caldecott and Newbery to others including the American Indian Youth Literature Award, the Américas prize, the Arab American Award, the Asian/Pacific American Award for Literature, the Carter G. Woodson Award, the Coretta Scott King Awards, the Dolly Gray award, the Ezra Jack Keats Award, the Middle East Book Award, Notable Books for a Global Society, along with the Pura Belpré, Rise Feminist (formerly the Amelia Bloomer Award), the Schneider Family, Skipping Stones Honor, South Asia, Stonewall, and Tomás Rivera Mexican American awards.

When it came to representations of gender across books and time, the study concluded, “[W]e find that females are consistently more likely to be visualized in images than mentioned in the text. This suggests there may be symbolic inclusion of females in pictures without their substantive inclusion in the actual stories.”

“Females are persistently less likely than males to be represented in the text of books in our sample overall and over time,” the study noted. “This finding is consistent across all of the measures we use: pronoun counts, specific gendered terms, gender of famous individuals, and predicted gender of character first names.”

Such studies provide more impetus for libraries to seek outstanding representation in their collections and cull outdated titles. Fortunately, these days, exposing children to high quality books about inspiring women is easier than ever.

Chelsey Philpot is a journalist and YA author. She teaches writing at Boston University.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!