Jewish Joy and the 'Little Women' of the Lower East Side | Opinion

When they were first published, Sydney Taylor’s books not only planted a flag for Jewish identity but also for Jewish joy, and today remind readers that Alcott's March sisters haven't cornered the market on getting by on love and little else. For Women's History Month, we remind readers of Sydney Taylor's origin story.

A review came back of Richard Michelson’s One of a Kind: The Life of Sydney Taylor. It was a positive review in most ways, covering the woman who, before her name was emblazoned across the Sydney Taylor Book Award, presented annually by the Association of Jewish Libraries to outstanding books for children and teens that authentically portray the Jewish experience, was simply Sarah Brenner. She was born in 1904 on the Lower East Side of New York City, when not all tenements had yet been converted from gaslight to electricity.

One sentence in the review stopped me. “While this is a powerful story of a pioneer author sharing a cultural identity, Taylor’s books are likely not familiar to many modern readers, which will impact this title’s appeal.”

Not familiar? I might have moved to New York because of All-of-a-Kind Family. At the editorial meeting that afternoon, I polled the team, who range from 25 years younger to far far younger. They did not do the polite thing of saying wanly, “I think I’ve heard of those books.”

They knew the esteemed book award; this was just after we’d all worked to link reviews to Youth Media Award winners. But just as few people really know much about Randolph Caldecott, Sydney Taylor, who wrote five books about a happy, raucous, very poor family, is even more of a mystery to today’s readers. For Women's History Month, maybe it's time we remind everyone of Sydney Taylor's origin stories.

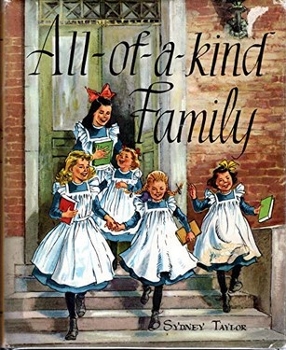

Taylor didn't begin telling her growing-up tales till she had a daughter; once she had written those stories down, her husband secretly submitted the manuscript to a publisher. First came All-of-a-Kind Family in 1951, followed by More All-of-a-Kind Family, All-of-a-Kind Family Downtown, All-of-a-Kind Family Uptown, and Ella of All-of-a-Kind Family. These were step-and-stairs little girls of all ages, like Louisa May Alcott’s Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy; but here they were Ella, Henny, Sarah, Charlotte, Gertie, and the bundle born in the first book, baby Charlie.

[Read: Jewish Joy: Celebrate Jewish Joy with Fresh-Baked Treats]

I identified with them mightily. Like my grandmother, Ruthie, they bought penny candy with carefully hoarded coins—how could the Lower East Side children and those of Clarion, IA, be so similar? Unlike us in our one- and two-story suburban homes, they dusted parlors, dressed in uniforms, and sailed out of a tenement to go to school, already hungry as they passed pushcart men with steamed potatoes, or roasted nuts—Taylor made these sights and scents as familiar to me as biking to a grocery store.

You all probably think that the whole mirrors, windows, and sliding doors thing doesn’t apply to a white-haired woman from the Midwest—haven’t we got enough stories? But is anyone “seen” enough? I recall my relief, reading and then watching I Remember Mama that there were Norwegians or Scandinavians who were not wildly inventive redheaded orphans like Astrid Lindgren's Pippi Longstocking, or worse, pillaging marauders in the worst of the Viking tropes. I needed to see the idealized friendships of the “Betsy-Tacy” stories by Maud Hart Lovelace set in a veiled Mankato, MN, not far from where I grew up, and where I met my first little Syrian girl, because at the turn of the century, Lebanon was occupied by Syria. I later married a Lebanese man.

I understood the house across the street, where a boy named David was raising himself while his single mother worked long hours as a nurse, because of the “Beany Malone” stories by Leonora Mattingly Weber. Beany was the motherly girl who tended her widowed father, a newspaper editor who worked long into the night but was always there for a good talk, like that other widower, Nancy Drew’s dad. There was so much compassion in these books for another sort of family than ours, imperfect as ours was.

All-of-a-Kind Family was given to me as a birthday present by my father’s little sister. Susie had just converted to Judaism in advance of her marriage to my uncle-to-be. Only 14 years older than I was, Susie always gave me hardcover books for special occasions, including the ghost stories of Henry James and Edgar Allan Poe, a first edition of The Hobbit, a boxed set of "The Lord of the Rings" trilogy, and then, one day, Webster’s Collegiate Thesaurus. Her father, Grandpa Olson, put a typewriter with that one.

All-of-a-Kind Family was given to me as a birthday present by my father’s little sister. Susie had just converted to Judaism in advance of her marriage to my uncle-to-be. Only 14 years older than I was, Susie always gave me hardcover books for special occasions, including the ghost stories of Henry James and Edgar Allan Poe, a first edition of The Hobbit, a boxed set of "The Lord of the Rings" trilogy, and then, one day, Webster’s Collegiate Thesaurus. Her father, Grandpa Olson, put a typewriter with that one.

Taylor's books were immersive. There was a scene of someone cutting out an insole from cardboard to make worn shoe good as new. Reading about these things in 1968, the year of political assassinations, when the world seemed out of control, reassured me. There was a warm kitchen. Things could be fixed. And while I loved the rituals of Westminister Presbyterian Church, where I sang in the choir, the calm of Friday Shabbot was far more reassuring as Mama covered her head and lit the candles. The oldest girl, Ella, kept watch, Henny made mischief, and the small girls were coddled by all, as Alcott’s Amy was.

[Read: Going Beyond All-of-a-Kind Family with More Recent Books about Jewish Life]

After Taylor's death in 1978, her husband established the Sydney Taylor Award, which had the positive effect of so many more wonderful books bearing her name. Every year, it's one of the most eagerly anticipated announcements at the YMA. While I understand why modern readers do not know the books, they should. We glimpse the Civil War and the normalized do-gooding of Alcott’s New Englanders through Greta Gerwig’s and all the other versions of the movies of Little Women, and pieces of U.S. history through the American Girls franchise. We need the more realistic, but glowing homes of the Lower East Side as they were; we don’t need the sanitized Gilded Age mansions of recent broadcasts without the origin stories of those steel and train barons, too.

Jewish joy brought me joy, and maybe even brought me to New York. I want Sarah Brenner’s books—Sydney Taylor’s books—to remind us that the March sisters don’t have a corner on the market of getting by with little more than a few pennies, family, and more than a little love.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!