"Abnormal Standard Time": Barbara Dee's Message to Kids Living Through a Pandemic

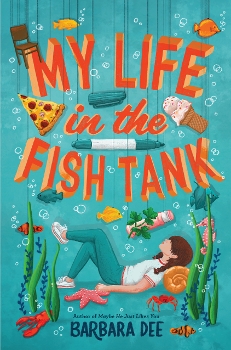

The middle grade author reflects on loneliness and survival in her latest novel, My Life in the Fish Tank, and its unintentional ties to the COVID-19 pandemic.

|

Photo by Carolyn Simpson |

My Life in the Fish Tank is not about the pandemic. But its subject—a family dealing with mental illness—may speak to middle grade readers in a way I hadn't anticipated.

Fish Tank is about 12-year-old Zinny, whose older brother Gabriel is diagnosed with bipolar disorder. Zinny's parents tell the three kids in the family to keep Gabriel's condition "private," which to Zinny means "secret." Carrying the burden of that secret isolates her from friends and classmates, as well as from teachers who try to lend support. Confused and anxious, Zinny feels trapped in her own personal "fish tank," safe but cut off from others—and also, in a weird way, on display.

Of course, when I wrote this story I wasn't imagining the isolation caused by COVID-19, or how we're all paradoxically “on display" on our fish tank–shaped computer monitors. But as I think about the stressors on kids' mental health in these days of quarantine, social distancing, and remote learning, I can't help but think that Fish Tank seems particularly of the moment.

I know that many middle grade kids, already feeling lonely and isolated, have also been struggling with a lack of structure. Sleeping late, staring at screens all day, seems like a seventh grader's dream—at first. But after a few weeks, or even a few days, it's easy for kids to feel adrift, nostalgic for the comfort of routines and schedules.

In Fish Tank, Zinny reflects on how the family crisis has altered their sense of time:

Sometimes I think we should have different systems for telling time. I mean like one system for when you go to school, hang out with your friends, play soccer on weekends, blahblahblah. We could call it something like Normal Standard Time.

But there would also be another system, another calendar completely, for when things get weird, or when bad things happen...some kind of new, not-yet-invented time measurement. Abnormal Standard Time.

To deal with both her isolation from peers and her sense that life has gotten "abnormal," without structure or predictability, Zinny copes by turning everything into a joke. These jokes help to deflect her friends' attention from Gabriel's illness, as well as to distract her little brother Aiden from his school assignment to deliver a "how-to" speech. When Zinny feels too anxious to sleep, she lies in bed thinking up silly, surreal "how-to" topics intended to make Aiden laugh.

It's an altruistic impulse. But I have to say I worry about kids like Zinny, the "easy," "good," "cheerful" kids who may appear to be smiling and joking, functioning normally, taking care of others, but are actually bottling up their own feelings of anxiety and/or depression. One of the lessons Zinny learns is that keeping things secret, hiding your emotions with humor, can be unhealthy. Self-care involves self-expression—sharing feelings (even the hard ones) with friends and confiding in adults like her guidance counselor, Mr. Patrick. Will sharing your troubles make them disappear? No, but they may feel lighter on your shoulders.

Zinny learns something else about self-care: Even when you're going through a challenging time—like a pandemic or a family mental health crisis—you shouldn't sacrifice your own interests and passions. Zinny thinks she needs to be home for Gabriel, giving up her summer at a marine biology program. But her mom tells her: "Whatever's going on with Gabriel, it's important for us—our whole family—to keep doing the stuff we care about. All the things that make us who we are." So (spoiler alert) in the end Zinny does attend the program, despite worries about her brother, and has the best summer of her life.

For many kids in these days of the pandemic, "the stuff they care about" is off-limits, as even schools that have returned to some form of in-person instruction have canceled sports, music, art, and theater programs. But I keep hearing about kids who have discovered passions for things they can do in isolation, like baking and skateboarding, even novel-writing. One key to maintaining mental health during times of crisis is being flexible, open to new experiences.

And that includes friendship. Some parents have told me that as the pandemic wears on, they're worried that their kids' social circles are shrinking. Zinny is hurt when she's rejected by her friends—but that rejection also makes her open to friendships with kids in the guidance group she reluctantly joins. If you've read any of my other middle grade novels like Maybe He Just Likes You or Star-Crossed, you know that I often write about expanding and contracting friendship circles; they're a part of middle school life, pandemic or not. A traumatic event can actually help a kid grow, challenging her to step away from toxic relationships and to consider what it means to be a true friend.

But perhaps Zinny's most valuable lesson comes from the lowly crayfish she's studying in science class, whom the class names Clawed. After she helps design a cozy fish tank, Zinny despairs when Clawed gets out. Eventually, she understands that "even if you set up the best tank...he might still try to escape. You can't control everything, and you can't predict everything, either. The same thing with people." Zinny has learned that loving her older brother doesn't make her responsible for his illness or his self-destructive behavior; the best she can do for him is to "keep her eyes open" and take good care of herself.

My hope is that kids will emerge from this pandemic with a sense of acceptance; understanding, as Zinny finally does, that "everything can happen" in nature, and if you need help, that's okay. I also hope Fish Tank shows that even in isolation, there are ways of reaching out to connect with others, if you remain open and flexible to new arrangements, like pods or guidance groups.

And I hope readers will take comfort in the book's last sentence: "Survival is realistic." Not the most utopian pronouncement, I know, but one that feels right for this Abnormal Standard Time.

Barbara Dee is the author of 11 middle grade novels published by Simon & Schuster, including My Life in the Fish Tank, Maybe He Just Likes You, Everything I Know About You, Halfway Normal, and Star-Crossed. Her books have earned several starred reviews and have been named to many best-of lists, including the Washington Post’s Best Children’s Books, the ALA Notable Children’s Books, the ALA Rise: A Feminist Book Project List, the NCSS-CBC Notable Social Studies Trade Books for Young People, and the ALA Rainbow List Top Ten. Barbara lives with her family, including a naughty cat named Luna, and a sweet rescue hound named Ripley, in Westchester County, New York.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!