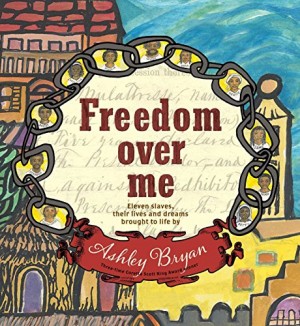

Ashley Bryan's "Freedom over Me" | An Interview

Consummate artist and poet Ashley Bryan burst onto the children’s literature scene in the 1960s and since then has been a distinguished presence; his contributions to the field have centered on the African American experience and culture. In his most recent book, Freedom over Me (S. & S; Sept. 2016; Gr 4-8 Up), the recipient of numerous artistic and literary awards and a three-time Coretta Scott King award winner imagines the lives and dreams of 11 enslaved men and women, who, in the summer of 1828, were offered for sale alongside hogs, cows, and cotton through the estate of Cado Fairchilds.

Consummate artist and poet Ashley Bryan burst onto the children’s literature scene in the 1960s and since then has been a distinguished presence; his contributions to the field have centered on the African American experience and culture. In his most recent book, Freedom over Me (S. & S; Sept. 2016; Gr 4-8 Up), the recipient of numerous artistic and literary awards and a three-time Coretta Scott King award winner imagines the lives and dreams of 11 enslaved men and women, who, in the summer of 1828, were offered for sale alongside hogs, cows, and cotton through the estate of Cado Fairchilds.For each person identified, Bryan offers two poems and images; an up-close, frontal portrait against a collage of archival documents—auction notices, bills of sale, advertisements—accompanies the verse account of each person’s daily life, while the dream poems rest on bold tones, opposite an expressive scene featuring the person surrounded by a field of vibrating colors. Today Bryan, professor emeritus, Dartmouth College, lives on Little Cranberry Island off the coast of Maine, where he has established The Ashley Bryan Center. We reached him there by phone.

In your author’s note you mentioned that you purchased a collection of “slave-related” documents dating from the early 19th century. Do you collect historical documents?

No, it was just by chance that I acquired these. About 10 years ago, right here in Maine, I saw an advertisement for an auction that included Civil War memorabilia and slavery-related documents. I went right over. I bid and was able to buy 20-odd documents from 20 estates dating from the 1820s to the 1860s: sales of cows, cotton, and corn—and individuals.

Included in those documents was the 1828 “Fairchilds Appraisement of the Estate,” which lists the names, genders, and prices of 11 enslaved people offered for sale. Do we know anything else about these individuals? Absolutely nothing. Everything in Freedom over Me [outside of the documents reproduced here], I made up. After extensive reading on the subject, I created the 11 individuals, giving them each a job and an age. It was only then that I asked them to speak to me….

You mentioned that you began the book by painting portraits to go with the names and by studying those images, listening for their voices.

Yes. The features of the 11 are based on family members and friends, which made them very close to me. It was only once I could actually see them that I asked: Will you tell me who you are? Where do you come from? What is your background? Tell me about your work. Then finally, what is your dream?

Were any voices louder than others?

No. No one voice will give an overall view of slavery time. You must read about all 11 to get that.

"Peggy" by Ashley Bryan from Freedom over Me (S. & S. 2016)

In the Fairchildses’ appraisement, each person is listed by name. Your poems acknowledge those names, but the dream poems provide their African names, and, often, their personal histories. Can you talk about those choices?

I gave them the names written on the document I purchased, but I asked them to tell me their real names and the meaning of those names. This was important to make them real people, people with identities. “Peggy,” what does that name mean to her? She says, “On the Naming Day ceremony/my parents named me/Mariama, ‘Gift of God.’/‘Mariama! Mariama!’/sings on in me.’” So while she is called Peggy, what she hears is Mariama.

Particularly moving is when given a voice, we hear how empowering each individual’s skill, trade, or talent is, whether it be basket weaving, healing, metal work, or music, and the moments of joy and pride it provided.

You see the skills and knowledge of African slaves in everything that was created in America, from rice planting to carpentry. When the president’s wife recently said, “We live in a house built by slaves,” people were surprised. The kind of work that these men and women did, even their knowledge of indigo, was important at that time. So much of what the United States is built on is due to the labor, intelligence, and skills of these people, viewed only as property with a price.

A prevalent theme in the book is the relationships that they were forced to leave behind and those that they formed with one another.

All 11 spoke to me of this; I made them a family. Peggy, the cook, is in a privileged position because she is in the big house, but she is not separate. It was important to show how close they were, that they were an interrelated group of human beings who helped each other, who loved one another. But, who at auction would be sold apart.

The strength of these men and women comes from their community and their talents and skills and the untouchable “inner life,” the “precious secrets” that you reference, where hopes and dreams lie.

We all have dreams, but slaves were never asked about theirs. We see them picking cotton, shepherding animals, building cabins, working. When I showed my extraordinary editor, Caitlyn Dlouhy, what I had written, she asked me to tell her more about these people. It’s then that I hit upon the idea of the dreams. When I shared one with Caitlyn, she said, “Ashley, that’s the way.” In these poems, I tried introducing things people may or may not have known about the experiences of these men and women. Sixteen-year-old John says, “I never knew my mother and father./We children worked in the fields/like grown-ups.” John’s a carpenter, a messenger between houses, and an artist, who wonders how art came to him. I identified closely with that boy, his spirit. All my life I’ve said that no matter what I experienced, nothing would keep me from drawing. While creating this book I saw myself, a black man, reading, drawing, and painting freely.

As readers, we project our hopes onto these people, but as we leave their stories, we don’t know about their lives after the estate sale. Has anyone been able to discover what happened to them?

No, a study of that estate that would be a good project for a sociologist. Almost all the documents I purchased note a place, but the Fairchildses’ appraisement didn’t. Initially I placed the story in northern Virginia. My editor suggested that I leave that out and let readers decide where it takes place. Slave sales occurred in both the North and in the South. Caitlyn also suggested that my author’s note should indicate that the terms boy, man, girl, and woman were used with no regard to the person’s age during this period.

Your knowledge of African American history and culture is vast. Were there aspects of it that you felt necessary to steep yourself in to create this work? I did have a strong background in this history when I approached this book, but when I immersed myself in the detail, what it really meant to be enslaved, it became difficult for me to write. I learned that a law was passed regarding the sale of Africans in the United States. Why? Because they were breeding slaves in the United States, and the sale of Africans was competition. When sold, these men and women sometimes had to walk for weeks to arrive at the new estate. People would hear them weeping as they walked…. That intimate sense of their experience deeply moved me, and it became harder and harder to work on the book. But I haven’t stopped reading… We are learning more and more about what was transpiring during this period all the time. Freedom? Equality? It was always, “But not for blacks.”

Is there another book in the study of this period for you? Well, the Ashley Bryan Center has brought out boxes of material that I haven’t looked at for years, and I’ve been asked to work on a book about my time in World War II—now, 70 years later! I worked as a stevedore in our segregated army, and never during that time did I stop drawing—I have hundreds of drawings from then. You have to be in your 80s or 90s to be writing your World War II memoirs!  Listen to Ashley Bryan reveal the story behind Freedom Over Me, courtesy of TeachingBooks.net.

Listen to Ashley Bryan reveal the story behind Freedom Over Me, courtesy of TeachingBooks.net.

RELATED

Tide’s Journey

The Smushkins: ABC Zoinks

Whose Footprint Is That?

Our World: Vietnam

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!