How American Indian Storytelling Differs From the Western Narrative Structure

American Indian storytelling has enjoyed a major resurgence over the last 20 years. In this guest essay, author Dan SaSuWeh Jones (Ponca), shares some of the incredible difficulties it's been through in the past 100 years or more, followed by a closer look at some of the traditions of American Indian storytelling.

American Indian storytelling has enjoyed a major resurgence over the last 20 years. It has survived several attempts at eradication, largely by external forces. Here are some of the incredible difficulties it’s been through in the past 100 years or more, followed by a closer look at some of the traditions of American Indian storytelling.

Nonlinear stories

The first hardship for American Indian storytelling is that we don’t tell stories the same way Europeans do. We didn’t use the Western narrative or develop the Western mindset for telling and enjoying stories—a process first developed by Aristotle in which all plots have a beginning, middle, and end.

American Indian stories, and those of other Indigenous cultures, didn’t necessarily have a beginning or an ending. Most people who hear American Indian stories translated from a native speaker will have no idea what the story is about. That’s because that story might be just a segment of an ongoing story, with other plot points and characters missing. The story may be more about the journey than the resolution.

Today, it is a hardship for many storytellers to alter their native story to fit into mainstream society by giving it a beginning, middle, and end.

Forced to learn the Western way

Forced to learn the Western way

But that’s not the only problem. Because of education in the white man’s boarding schools, first established in the 1800s, most of our children and their parents were forced to learn the Western approach to telling and hearing a story.

The effect on our stories has been devastating. Indian students were forbidden to speak their own language, destroying the tradition in which mothers pass on stories in their native language to their children, to teach the values and lessons of their people. Fortunately, not all storytellers were swept up in this system, and many of these stories escaped the disaster of the boarding school era. To keep these wonderful stories alive, storytellers today work to maintain traditional structure that is nonlinear, as opposed to the linear structure of Western stories.

I come from an oral tradition of storytellers opposed to the written tradition. There has been much debate as to which is more accurate. All I can say is that my people are very rigid in their beliefs about how stories and songs are passed down. This puts even more pressure on modern storytellers to determine how much they need to modify a story so our Western-minded youth can understand and enjoy their own tribal stories.

Style, methods, structure, and traditions of American Indian storytelling

As an example, an Indian story may begin with the ending or seem to start in the middle, then move to the beginning of the story. Many times, Indian stories don’t really end, but continue for a lifetime.

Many of the main characters in Plains Indian mythology never end. Not only are they immortal and indestructible—where they may be killed in one story and are right back at it in another—they also age with the listener. Coyote stories for children have childlike morals; for teens Coyote is a much rougher character; and, for elders only, grandpa Coyote is smart, and his stories are deep and filled with complicated plots and plans.

There are also great differences in Native ethics and, say, Christian ethics. All bodily functions are a natural thing, so the stories didn’t hold back on such human and animal activities. Sex was not considered an evil or taboo subject between consenting adults in traditional American Indians 150 years ago, so the stories didn’t shy away from that subject either.

The best example of Indian storytelling can be seen in what is called the Winter Count—a tribe’s record of its year of activities painted in picture grafts on a buffalo robe. If you don’t realize that it’s laid out in a nonlinear fashion, you would have no clue as to its meaning. It’s actually a very sophisticated way of creating what one could only call a “mind map.” You read it from the center as the picture graphs spin out in a spiral.

Different types of stories

Different types of stories

This brings me to the different types of stories in a typical Indian Nation. First, there are instructional types, mainly for passing down how rituals or social events are to be handled, and how people are to conduct themselves. You can hear these at funerals, ceremonies, military events, Native American church services, or even social events like Hand Games or Give Aways. Other stories are private, just between a leader of a society and, for instance, their apprentice.

In my tribe, most important stories are held with the drum, in the form of songs. Some of these songs can speak of things that are ancient—and there are thousands of them. Many are stories of places we moved to; a good deal of them are war stories from major conflicts; and some are individual songs of bravery or humor, like our Horse Hunting songs (which are really about us stealing our enemies’ horses).

These songs are more like the Japanese poetry called haiku, in which just the main points or punch lines are told. The song might only say “he shot the arrow, he shot the arrow.” From that single line, the Head Singer, who holds the song, will know the full story, which might take 20 minutes to tell. Songs are the most rigid story form passed down in my tribe; the stories to the songs must be kept word for word.

Ghost stories are some of the more freely exchanged, even shared between tribes with different means of storytelling. When I was young, the stories were told more within the family groups that make up your clan. Today, the tribe will sponsor ghost storytelling events where participants come from across the tribe. Lately they have a contest for the scariest or most horrific story. It’s becoming a big event, and it’s great to see. The dynamics of a tribe are constantly changing, with many of our most dramatic coming from the youth, as it should be, a sign they are engaged in the tribe.

Of all the various storytelling types I’ve heard of or experienced, among the most compelling is that of the Inuit people who live far above the Arctic Circle. On certain occasions the head storyteller, a medicine man, will have his audience lie on the floor with their heads together, forming a circle. He begins his story, and the listeners drop off to sleep, all experiencing the stories in their dreams.

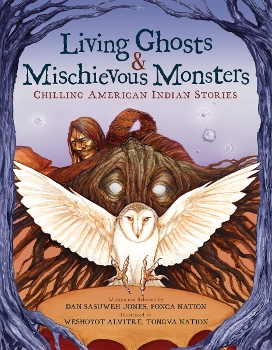

Dan SaSuWeh Jones (Ponca) is the author of Living Ghosts & Mischievous Monsters.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!