2018 School Spending Survey Report

A Touch of Grace

Grace Lin's new novel is a tribute to her late husband--and a reminder of what really matters

Photograph by Tsar Fedorsky/Getty Images for SLJ

From Grace Lin’s blog: June 19, 2007 Relief Even though I have been quiet about it, the last two weeks have been really brutal. Robert has suffered viciously, yet still soldiered on. I felt the least I could do was try to do the same. But the last few days have brought improvement and relief, and as it rains upon us, my creative seeds begin to sprout again… and it looks like I’ll be able to go to the ALA in Washington as planned. But more important than keeping the schedule intact is the hope that it gives us that all may be well someday… maybe even someday soon. June 20, 2007 Ah, methinks I jinxed myself for as soon as I posted Robert was better he took a backward step and I will not be able to go to ALA after all. Such is the way of the best laid plans. June 26, 2007 I am sorry to say that Robert is not having the results that we hoped for and the written word no longer brings me solace. As Robert’s body betrays him, so does the consolation of my blog. So for now during these hard times, I say goodbye—hoping to find hope in silence. In the two years since her husband’s death at the age of 35, Grace Lin has spent much of her time, whether by chance or on purpose, living up to her first name—with excellent results. The petite, self-effacing 35-year-old woman of Taiwanese ancestry lives alone in a two-bedroom apartment in a former schoolhouse in Somerville, MA. The high-ceilinged setting, with the indentation for the chalkboard still visible, is picture perfect for someone who earns her living creating children’s books. Lin is often asked how she became a children’s book author, and illustrator and the answer she gives on her Web site is that after earning her BFA in 1996, majoring in illustration, she worked in a children’s bookstore, researching the industry. She also attended numerous workshops and conferences, trying to make herself knowledgeable in the field and, as best she could, known, sending out thousands of color copies and postcards of her work. For many years, she subsisted on ramen noodles and a stubborn faith in her own future. It was at the bookstore, Curious George Goes to Wordsworth, in Harvard Square, that she met her future husband, who inquired about a book by Linda Wingerter. Lin said, “She is my friend.” Robert Mercer said, “Mine, too.” And it turned out that, unbeknownst to each other, they had all been classmates at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) in the mid-’90s, where Robert majored in architecture. He would later go on to Harvard to get a master’s in urban design and work for architect Frank Gehry. In the early days, Lin also supported herself designing personalized versions of trinkets and paraphernalia for a party company: paper plates, confetti, World’s Best Dad coffee mugs. “You know, the ones that say, 'Anyone tell you you’re terrific today?’” “Basically, I spent two years contributing to the world’s landfills,” she says. An unusual tone of self-satisfaction creeps into her voice: “And then, a wonderful thing happened. I lost my job.” Using the modest windfall she received after being laid off, Lin decided to pound the pavement in New York City, portfolio in hand, showing her work to anyone who would give her the time of day. The breakthrough came in 1998, when Harold Underdown, then a senior editor at Charlesbridge in Watertown, MA, just outside of Boston, called to say he loved her illustration entitled “The Ugly Vegetables” and asked, “Do you have a story to go with it?” “Yes, I do,” Lin said, even though she didn’t. “Great. Send it along.” “Sure,” she said, hurrying home to the computer and the drawing board and soon producing her first published work, a story about the author and her mother and the ungainly vegetables they used to grow. Published in 1999, The Ugly Vegetables was an American Booksellers Association “Pick of the List” and a Bank Street College “Best Book of the Year.” Since then, she has written and illustrated more than a dozen books, including picture books such as Dim Sum for Everyone! (Knopf, 2001) and Okie Dokie, Artichokie (Viking, 2003) and three novels based on her childhood experiences and Chinese fairy tales and myths (The Year of the Dog [2006], The Year of the Rat [2008], and the brand-new Where the Mountain Meets the Moon [all Little, Brown], already the recipient of three starred reviews, from Kirkus, Booklist, and SLJ). Lin’s work is an unabashed celebration of her background, and faithful readers have learned to rejoice in the lore she imparts, such as the need in Chinese households to throw away chopsticks with dents at the New Year because they’re said to chip away at the future, or that red is a lucky color that scares away evil spirits. These days, in addition to any income generated by her books, Lin makes about 30 school appearances during any given year, charging about $1,500 per visit. She also donates some of her work to an art auction run by the Boston-based Foundation on Children’s Books to subsidize author visits, for herself and others, at schools that otherwise could not afford them. She’s aware of how unfair it is to visit only schools that can afford her but also how it’s unfair to ask a struggling author to make appearances without compensation. The daughter of a doctor who specializes in kidney disease and a botanist who gave up her career as a scientist to be a stay-at-home mother, Lin grew up in an ordinary two-story white house in New Hartford, NY, the second of three daughters. All three girls had Chinese nicknames at home: Beatrice was “Lissy,” Grace was “Pacy,” and Alice was “Ki-ki.” As a child, Lin entertained several career options, including that of cashier because she thought you could keep the money (“I used to feel sorry for cashiers with short lines”). She dreamed of becoming a figure skater but soon realized she preferred drawing herself as an ice skater more than actually being one. In the seventh grade, Lin entered Landmark’s “Written and Illustrated By… Contest for Students” and won fourth place, earning $1,000, which would be applied to college tuition when the time came. Her book was called Dandelion Stories and was about flowers that talked to one another. “I always used to wonder who came in first that year,” she says, “and then I found out it was Dav Pilkey, author of Captain Underpants.” Her forgiving smile indicates that if you have to lose, it might as well be to a future heavyweight. The Chinese have an expression for difficult challenges, calling them “cold doors.” (You can read more about this in Lin’s second novel, The Year of the Rat.) Pursuing a career in the arts is considered one of them. Despite pressures to get a degree in science, Lin took the risk of “slightly horrifying” her parents by choosing to go to RISD, where in one class she was told to “make a violin out of cardboard using no glue or tape” (“The secret,” she says, “is all in the tabs”) and in another class received the even more high-concept instruction from a teacher who simply said, “Your assignment today is blue.” During a semester abroad in Rome in 1995, she realized that her classical training had blinded her to her own heritage: “I knew more about Roman history than I did about my own cultural history. I spent a lot of time in Rome, copying, copying, but no time creating my own vision.” She vowed to find her own voice and personality, the first step being to stop politely mixing colors and instead dumping the paint out of the tubes and using them with bold generosity. Early on, Lin’s sense of triumph over her accomplishments was challenged when a fellow striving author/illustrator said, “It’s good you’re using your culture—multicultural books are hot now. That’s what’s getting you published.” Lin worried that she had attained success through a “back window.” “Was I only getting published because of my heritage and subject matter? Was I cheating? Was I selling out my culture for a career?” When an editor subsequently suggested that she create a Caucasian boy as a character in order to avoid being typecast, Lin realized that being considered “publishable without my heritage was a pale consolation prize when compared to creating a book that was true to my vision.” She does not discount broadening her so-called cultural base in the future. “I would do a book on anything if it felt right,” but for now she considers her work a “gift not to be squandered on something soulless. And my soul is Asian American.” Recently, seated at her dining room table, Lin shared the slide show she offers to students. Nudging back the small-framed glasses that give her an air of earnestness and perpetual curiosity, she berates herself for speaking too fast under normal circumstances and said she finds her PowerPoint presentation helps her to slow down. The show is interlaced with pictures from her past, from the great masters, and from her own work. “I grew up in a normal nondescript two-story house,” she begins, with a slide of a plain white dwelling to prove it. She and her family were the only Asians in her town, and she struggled with the idea of assimilation, seeing herself as part of the majority. An awakening of sorts occurred when her elementary school put on a production of The Wizard of Oz and, like all the other girls, Lin endlessly practiced for her audition in the playground, singing “Over the Rainbow.” Her career in musical theater was cut short in the third grade when a classmate said, “You can’t be Dorothy. Dorothy’s not Chinese. Dorothy is American.” Her friend had called her Chinese. “But I did not feel Chinese. I spoke English, I watched Little House on the Prairie, learned American history, and read books about girls named Betsy and boys named Billy. But I had black hair and slanted eyes, I ate white rice at home with chopsticks, and I got red envelopes for my birthday. Did I belong anywhere?” When the teacher called her name to try out for the play, Lin passed, saying that at the time she didn’t feel so much “angry, as stupid.” This incident spurred the dawning consciousness of her racial differences, and she came to realize that the pictures in her Asian-themed books such as The Five Chinese Brothers weren’t as lovely as those in her favorite mainstream books. The translations were clumsy, and, besides that, they were misleading: “Not all Chinese men have long ponytails and drive rickshaws.” She has traveled in Asia: about a half dozen times to Taiwan to see family, once to Hong Kong for a school visit in March of 2007, and once to China in November of 2008 to see the landscapes and buildings in person, marrying her views of them with notes borrowed from classical works, such as the swirls in Van Gogh’s Starry Night, her favorite painting of all time. Lin possesses a winsome air, evidenced in her fanciful dress, her love of desserts (she claims to make excellent coconut sorbet and red velvet cupcakes), her attraction to whimsical trinkets, such as a change purse shaped like a fish, her favorite mode of transportation (a bike), her distaste for the telephone, and her tendency to take vacations in places like Prince Edward Island to see where Anne of Green Gables took place. Even her book dedications can be tongue-in-cheek, such as in The Year of the Rat: “If you are reading this book, it is dedicated to you.” A certain aura of playfulness pervades the living/dining area in her home, enhanced by the colorful art on the walls and the walls themselves, painted “green moth,” which she chose because it was bright and happy, but also relaxing. The windowpanes are a color called “Tiffany glass,” not white but a pale green to soften the look of the moldings against the walls. The orange in the kitchen is “tangerine dream,” to contrast with the very white cabinets and countertop. The crisp stern whites were chosen by her husband, Robert: “He was a modernist.” “He was young and healthy, and he thought the pain he felt in his thigh came from a torn muscle,” Lin says of her husband, who was eventually diagnosed in 2001 with Ewing’s sarcoma and died in August of 2007. The first time the cancer hit, Lin remained philosophical: “OK, this is a delay.” The second time, slowly, she started to realize he wasn’t getting any better. A switch went on: “I have to do what I have to do.” She visited him in the hospital. He’d be sleeping, and she’d be writing furiously. Often while her husband was dozing, she would take refuge in working at his bedside. “Without the financial pressures brought about by his illness, I might not have become so business-oriented. I didn’t have an option,” she says, producing three books in 2006. She left one publisher and stopped worrying about “whether they’re going to like me anymore.” “I wanted to finish what became the new novel before he died, but I was only halfway through. I was so devastated. I thought I was going to stop writing children’s books entirely. But then a friend, Janet Wong, said, 'Perhaps it’s better this way. If you had finished it before he died, you would feel you couldn’t change anything.’” “I realized,” she says, “I could change the ending.”

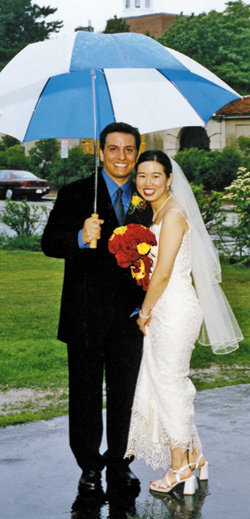

Grace and Robert on their

wedding day, June 17, 2001. Photograph courtesy of Grace Lin.

Pulitzer Prize–winner Madeleine Blais (mhblais@journ.umass.edu) teaches journalism at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst and is the author of the young adult nonfiction book In These Girls, Hope Is a Muscle (Atlantic Monthly, 1995).

RECOMMENDED

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!