Public Library Summer Programming Is Vital to Communities, SLJ Survey Shows

These services meet the needs of children and families across the country, with programming ranging from robotics to summer meals to ever-popular reading challenges.

|

For the full results of SLJ’s Public Library Summer Programming Survey, download the report. |

How important is summer programming to the lives of communities and their families? Extremely, a new survey from SLJ shows. These public library services meet the needs of children and families with programming ranging from robotics to summer meals to ever-popular reading challenges.

Across the country, 97 percent of all public libraries increase their youth programming in the summer months, according to the 773 librarians who responded to our national survey. Their facilities, of varying sizes, serve 106,300 people on average across the Northeast, Midwest, South, and West, in urban, suburban, small town, and rural settings. Survey topics encompassed summer programming, including funding, partnerships, and incentives.

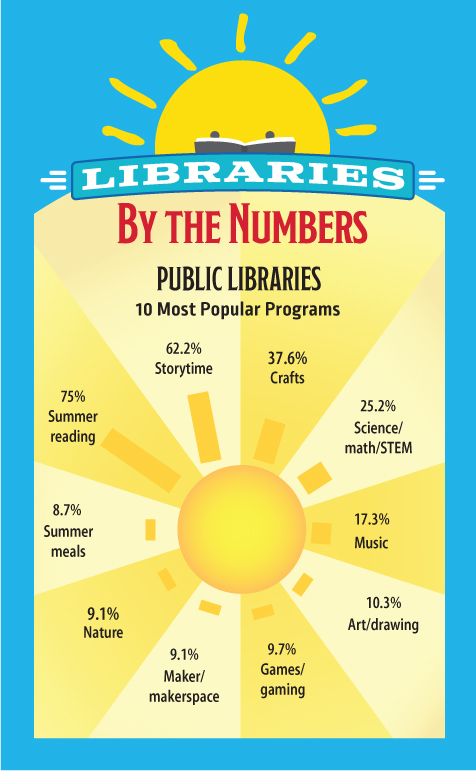

The most-offered programs across the board in 2018 reflected a mix of reading, art, tech, and outdoor focus. The top three programs were summer reading initiatives, storytime, and crafts, delivered by more than 90 percent of respondents. “Our summer reading program attendance is increasing by thousands each year,” notes Rebecca Ballard, children’s librarian at Oconee County (GA) Library.

The most-offered programs across the board in 2018 reflected a mix of reading, art, tech, and outdoor focus. The top three programs were summer reading initiatives, storytime, and crafts, delivered by more than 90 percent of respondents. “Our summer reading program attendance is increasing by thousands each year,” notes Rebecca Ballard, children’s librarian at Oconee County (GA) Library.

Ranking fourth are STEM initiatives, offered by about 70–75 percent of libraries. Games and gaming activities are provided by 68.8 percent of all libraries and 91 percent of facilities serving populations of more than 500,000. The average percentage balance of reading and learning-based programming is 54 percent reading and 46 percent learning.

Suburban and large libraries serve the broadest programming array, while urban libraries provide more writing, art/drawing, sound production, and summer meal programs. Science and tech are more common in the South, while art, sewing, and fiber arts were most prevalent in the Midwest. Tutoring is available almost twice as frequently in the Northeast than elsewhere.

Spotlight on summer meals

Libraries are also playing a major role as providers of summer meals for children. Approximately 14 percent of U.S. families—about 15.3 million children—are living in what the United States Department of Agriculture calls “food insecure households.” During the school year, some 22.1 million kids receive free and reduced-price meals through the National School Lunch Program (NSLP). In the summer, that number drops to 3.8 million—about one in six of the NSLP students. Libraries have stepped up to fill that critical gap, with 42.8 percent of respondents reporting that summer meals are the third most popular summer initiative at those libraries that provide them. This program ranks right after storytime, the second most popular, at 66 percent, and summer reading activities, the most popular, at 77.7 percent.

Libraries are also playing a major role as providers of summer meals for children. Approximately 14 percent of U.S. families—about 15.3 million children—are living in what the United States Department of Agriculture calls “food insecure households.” During the school year, some 22.1 million kids receive free and reduced-price meals through the National School Lunch Program (NSLP). In the summer, that number drops to 3.8 million—about one in six of the NSLP students. Libraries have stepped up to fill that critical gap, with 42.8 percent of respondents reporting that summer meals are the third most popular summer initiative at those libraries that provide them. This program ranks right after storytime, the second most popular, at 66 percent, and summer reading activities, the most popular, at 77.7 percent.

Regionally, summer meal programs are provided more frequently in the South and in urban libraries. When asked whether they choose to offer summer meal programs to support those “who are food insecure,” 28.6 percent of respondents from branches with between 100,000 and 499,999 patrons stated yes. That figure jumps to 44 percent at facilities serving more than 500,000 people.

Reading incentives

To boost engagement among young children and teens, nearly all public libraries, 97 percent, distribute prizes and other incentives for participation in reading programs. These are particularly popular with younger kids. “I found they were effective at gathering interest and bringing children into the library. But at the end of the program, children found reading for themselves fun and didn’t consider the prizes for reading. It was awesome!” says Tammy Batschelet, children’s librarian at Dare County Library in North Carolina. “We have found that for the younger crowd, something as simple as putting a sticker on a reading log can be an incentive,” adds Nancy Hargrove, youth services manager at Troy-Miami County (OH) Public Library.

“We are hoping to generate a larger number of teen [participants] this year with a few extra motivating incentives,” adds Marisha Crowder, library assistant and teen specialist at the Monroe County Library in Forsyth, GA.

“We are hoping to generate a larger number of teen [participants] this year with a few extra motivating incentives,” adds Marisha Crowder, library assistant and teen specialist at the Monroe County Library in Forsyth, GA.

Children receive free books at 84 percent of libraries, the most commonly used incentive. Coupons for local businesses are also popular (71.5 percent), along with bookmarks (55.2 percent) and small items such as stickers, small stuffed animals, pencils and erasers, and temporary tattoos.

Fourteen percent of libraries offer raffle baskets, and fewer than 10 percent provide prizes such as book bags, T-shirts, or the removal of fines. The Smyrna (DE) Public Library even offered a $100 gift certificate and a trophy to the students who read the most, according to former library director Beverly Hirt. Eighty-two percent of respondents agree that incentives are effective at motivating children to read.

While librarians continue to try to find ways to expand giveaways, including those for adults, finding the funding for these prizes can be a sticking point. “We need more teen and adult incentives,” said Lorelei Bidwell, librarian I at Anne Arundel County (MD) Public Library. “It’s always a matter of budget, which I understand, so I do try and create these opportunities at my branch at least.”

About 15 percent of libraries made an effort to align summer reading participation with academic performance in order to address the “summer slide.” The largest libraries, serving 500,000 or more, along with libraries in the South are most likely to make this effort.

Funding

Libraries across the country budgeted a median of $1,960 per location in 2018 on all summer youth programming—with suburban facilities, along with those in the Midwest and the South, budgeting the most.

Libraries across the country budgeted a median of $1,960 per location in 2018 on all summer youth programming—with suburban facilities, along with those in the Midwest and the South, budgeting the most.

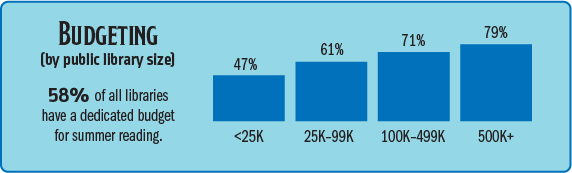

Just over half of libraries surveyed—58 percent—have a dedicated budget just for summer reading activities. Libraries had a median spend of $1,727 per location in 2018 on summer reading activities. Most expect to spend the same amount in 2019 as in 2018, although larger systems anticipate that they may spend two to four percent more.

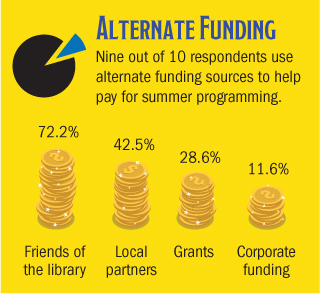

Where does the money for summer programming come from? Nine out of 10 libraries used alternate funding sources to help pay for their initiatives in 2018. The majority of those, 72 percent, can thank supporters and Friends of Libraries groups for that help. Just fewer than half, 43 percent, relied on local partners such as local businesses, parks/nature centers, and museums.

Where does the money for summer programming come from? Nine out of 10 libraries used alternate funding sources to help pay for their initiatives in 2018. The majority of those, 72 percent, can thank supporters and Friends of Libraries groups for that help. Just fewer than half, 43 percent, relied on local partners such as local businesses, parks/nature centers, and museums.

Grant money helps 30 percent of libraries, with rural and Southern facilities the most likely to tap into those resources. Finally, 12 percent of U.S. libraries receive corporate funding, most frequently, libraries serving patrons in high-population areas.

Planning for individual communities

Planning these robust summer programs takes significant time, and many libraries—31 percent—launch their planning in January, with another 31% starting the previous fall. Two-thirds of libraries, or 62 percent, are planning by the end of the first quarter in March.

The size of a library system often impacts whether it will design its own program or adopt one out-of-the-box. While 72 percent of the smallest libraries will use a pre-created program, only 54 percent of the largest ones do. Initiatives such as the Collaborative Summer Library Program (CSLP) are popular with 64 percent of libraries.

“We have access to CSLP materials, but often modify their suggestions to best serve our audience,” said Lea Rosell, library director and teen service librarian for the Lewes (DE) Public Library, which serves between 10,000 and 25,000 patrons. “Much of what we do in the summer is not related to the materials supplied by CSLP.”

The number of branches tailoring pre-created initiatives to their communities rises to 80 percent for libraries serving half a million patrons or more, which can mean changing the kind of prizes offered, adding entertainment or a performer, or creating customized log sheets.

What does the future hold for summer at the library? Respondents say that these programs are only growing. “Summer reading is hands down the busiest time of the year. Our programs expand 100 percent and it is typically when we see most of the community, says Cindy Ambos, tween librarian at the South Brunswick (NJ) Public Library.

To keep new patrons coming back—ideally with their friends—a welcoming reception is key. “Often teens and children who do not come to the library…will meet a staff member who tells them about all the free and fun activities we are doing at the library, and lets them pick a book or do a craft,” said Debbie Allen, program coordinator for the Lewiston City (ID) Library. Young patrons “now realize all the public library has to offer them and their families for free. Summer reading helps get the word out to the underserved population, and friendly staff also makes a huge difference.”

For the full results of SLJ’s Public Library Summer Programming Survey, download the report.

Lauren Barack is the executive editor of GearBrain and a Loeb Award-winning journalist.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!