Making Great Strives: Building Confident Readers

Hi-lo books, graphic novels, and relevant narratives connect striving readers with books that engage them and boost literacy.

|

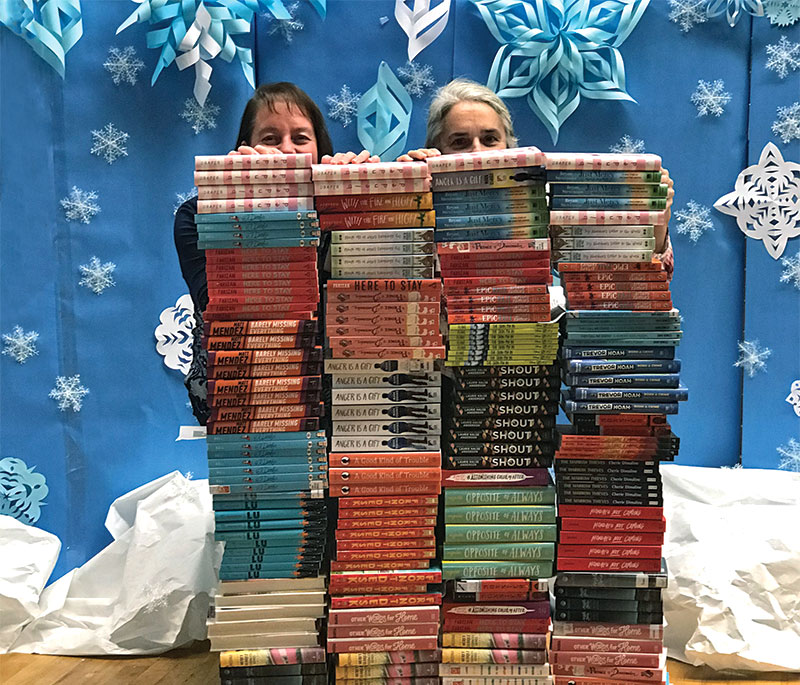

Michelle Annett (right) with assistant Linda Statt and a stack of Project LIT books for her Cascade Middle School students.Photo courtesy of Cascade Middle School (WA) |

Reading is challenging for most of the students at Cascade Middle School in Vancouver, WA. More than 60 percent of the nearly 1,000 students who attend Cascade are classified as striving or reluctant readers. But this doesn’t deter Michelle Annett, the school’s teacher librarian.

Annett, who’s been in the role for the last eight years, firmly believes that there’s a book out there for everyone, and she’s determined to help her students find it.

“I see it as my job to stock my library with books that students will see themselves in and connect to and then give them the support they need to clear whatever hurdle is in their way of loving reading,” says Annett, who spent 15 years teaching English and social studies at the middle school level before becoming a librarian.

The situation at Cascade Middle School is not unique. The latest National Assessment of Educational Progress results, released last year, found that students in fourth and eighth grade have lost ground in reading.

The test, known as the nation’s report card, found that only 35 percent of fourth graders were proficient in reading in 2019, down from 37 percent in 2017. The situation was even worse for eighth graders, with only 34 percent proficient in reading, down from 36 percent three years ago.

This lack of reading proficiency presents a challenge for school librarians around the country. How do you get a child who struggles to read excited about books? How do you even get them to come into the library when they associate reading with drudgery and failure?

Connecting them with books that resonate, for one. Annett has had success with the Project LIT Community initiative, a national grassroots program designed to encourage students to read.

The Project LIT Community includes educators and kids who work to promote literacy and make sure students have access to “culturally relevant” titles.

Annett started a Project LIT chapter at her school last year, inviting the 30 lowest scoring students of color in each grade level to participate. She chose those students because the Washington state education agency had recently designated her school for special help, since students in four identified categories had failed to show adequate growth. The school already had programs in place for two categories, English language learners and special ed students, but none for African Americans and students who represented two or more races.

“I made a big deal out of the invitation, telling them they were selected at random and emphasizing food and fun for our book groups,” says Annett. “Of the 90 invited, only three students declined to participate.”

The students chose what they wanted to read from a list of middle grade and young adult titles provided by the program, which features books designed to make “students feel seen, heard, affirmed, and valued.”

Some books on this year’s list include The Epic Fail of Arturo Zamora by Pablo Cartaya, Dactyl Hill Squad by Daniel José Older, and With the Fire on High by Elizabeth Acevedo.

“Students have to have something that connects to their life experiences, whether that be the characters, the plot, or the format of the book,” says Annett. “Trying to force books on them that are ‘their reading level’ or ‘a classic’ is a recipe for teaching students to hate reading.”

Annett says the program has also made her confront her own reading bias.

“I know what kind of books I like, and those are the books I tend to talk up and share with students the most,” says Annett. “These titles tend to connect with our white students and certainly with the girls. What I like about Project LIT is that someone else is picking the books, so it naturally forces me out of my comfort zone a bit.”

At Annett’s school, Project LIT students were divided into book clubs, and she pulled them out of a different class once a week to read together. She used a grant from her school district along with outside fundraising to provide each student with a copy of the book.

“For some of my students, I don’t think they have ever owned a book,” says Annett. “As word got out around the school, many avid readers also asked to join. I accepted any student who asked to participate and our numbers grew.”

Today, more than 160 students take part in the program, and Annett has added a final meeting for each book that’s open to any student or teacher who’s read it.

“The conversations have been awesome, and the connections students are making with adults in the building have been significant,” says Annett.

For Carolyn Slavin, forming relationships with her students at Reed Elementary School in Cedar Park, TX, is a big part of her efforts to help striving readers.

If she knows a little bit about them, she can suggest books that they might enjoy. So she tries to have conversations with each of the 800 students at her school.

She also relies on graphic novels, which tend to be popular with all of her students. They particularly enjoy the “Dog Man” books by Dav Pilkey and anything by Raina Telgemeier, especially Smile, Sisters, and Guts.

“They still look like chapter books, and everybody checks them out,” says Slavin (pictured). Some of her students don’t check out hi-lo books because they can carry an association with lower reading skills. But “I have not seen anybody being like, ‘Why are you checking that [graphic novel] out?’” says Slavin. “They’re accessible to everybody.”

Other librarians turn to hi-lo books to help striving readers. These books that feature high-interest content at a lower reading level are designed specifically for students who struggle with reading.

Saddleback Educational Publishing specializes in hi-lo books. “The reading level of these titles ranges from pre-K to about fifth grade, but the maturity of the content is geared to students in third to 12th grade,” says Saddleback president Arianne McHugh. “You will not find a baby book at Saddleback. Even our lowest, emergent readers look age-respectful and depict story lines that are relatable to tweens and teens.”

The idea among some students and educators that a hi-lo book equals a “baby book” leads to a certain stigma around these titles, but Jen Besel, associate publisher of Black Rabbit Books, says that’s not fair.

“There’s a stigma against holding that maybe shorter book when all of your friends are reading a bigger, thicker book,” says Besel. “But what we would love for these kids to know is that these are full of content and they are not for babies in any way, shape, or form. They are meant for kids their age.”

Black Rabbit has been providing content for these students since 2015. The company calls its offerings hi/lo/info books; “info” refers to the interactive elements found in each title. These books use strategies such as colorful graphics and fact boxes to keep the students’ interest.

“That kind of interactivity will engage them in a way that a traditional text and photo book can’t,” says Besel.

Besel also stresses that these students are often misunderstood.

“These kids, they are readers, but they’re just not reading books,” says Besel. “They’re reading comic books maybe. They’re reading the dialogue on their video games. They’re reading the little stats on their Pokémon cards. Knowing that helped influence what we were looking for when we started to make the books.”

Annett bills hi-lo books in her library as “short books” and encourages striving readers to give them a try.

“I talk about the pride of accomplishment a person feels when finishing a book and encourage them to choose a book so they can experience that feeling,” she says. “I find these books work best with English language development students.”

The teacher at her school who works with English language learners reads Pigboy by Vicki Grant to her sixth graders annually. Some other popular hi-lo titles at her school are See No Evil by Diane Young and In the Woods by Robin Stevenson.

But she says these are still not the books her students who are learning English tend to check out.

“The ELL students want to have books that look just like their classmates’,” says Annett. “Because the hi-lo books are skinny and smaller in general, I think they tend to make those students self-conscious.”

She points out that her 230 hi-lo books had 239 circulations last year, compared to her 688 graphic novels, which circulated nearly 3,000 times last year.

All of Saddleback’s hi-lo books are in a series format to encourage students to keep reading.

“This is crucial to a beginning or reluctant reader,” says McHugh. “If they successfully finish a book they enjoy, we want them to have another one just like it to go to next. There is comfort in seeing the same font size, chapter count, and look and feel.”

|

April Stone (right) with a student at the Four Points Middle School library.Above: Photo courtesy of Four Points Middle School Yearbook |

At Four Points Middle School in Austin, TX, librarian April Stone says students avoid these books.

“They don’t seem interested in them,” says Stone. “They seem thin if you compare them to a typical novel. I think they interpret that as being an easy book.”

Annett says that opening the Project LIT book clubs to anyone who wants to join makes kids feel honored to be part of the program and removes stigma. It has also led to students making valuable connections outside the group.

She recalls one day when a reading group made up almost exclusively of African American eighth grade boys was reading Ghost Boys by Jewell Parker Rhodes in the library and some other students came in to work on a math project.

A Project LIT kid asked one of the math students what he was reading, and that sparked a lively discussion about Tears of a Tiger by Sharon M. Draper.

“That simple question, ‘What are you reading?’ sounded so natural and authentic coming out of these students’ mouths, no stigma, no ‘reading isn’t cool,’ ” says Annett. “That’s when I knew I had something special happening and that I was impacting the culture of the building.”

Marva Hinton recently wrote “Hip-Hop EDU” for SLJ.

Marva Hinton recently wrote “Hip-Hop EDU” for SLJ.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Sabine McAlpine

It is great to see a focus on striving readers. There has also been great success using large print books for striving readers. Many of the Project Lit titles are in large print and students see the books as more inviting and enjoyable to read.

Posted : Feb 12, 2020 05:18

Abby Smith

This was a great article! The stat that only 35 percent of fourth graders were proficient in reading in 2019 was very shocking. I think that the incorporation of graphic novels or hi-lo books is a great way to get students excited about reading. We will have to incorporate this at Garden Grove Unified School District!

Posted : Feb 11, 2020 08:27