Libraries in Charter Schools Play by Their Own Rules

Because campus autonomy is key to the charter philosophy, schools with libraries tend to align them with specific educational principles.

|

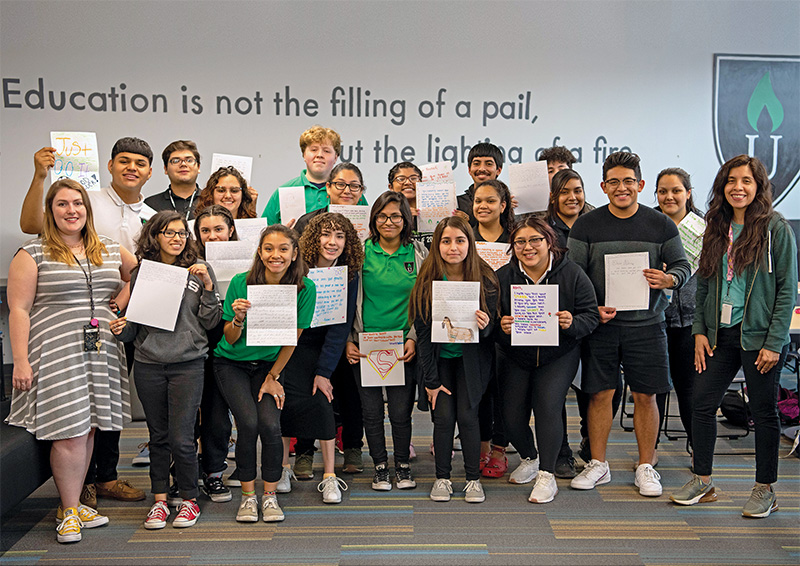

Students at KIPP University Prep in San Antonio, TX, with Savannah McDonough, International Baccalaureate (IB) English teacher (left), and IB librarian Jennifer Martinez (right).Photo by Pablo Cruz, KIPP Texas Public Schools |

The library at IDEA Monterey Park, a charter school in San Antonio, TX, isn’t just quiet. It’s silent. The students wear earmuffs to block sound and communicate with hand signals if they need to get up to use the restroom, take an Accelerated Reader (AR) quiz, or select a new book. The rest of the time, their heads are bent over their books in private carrels.

Intensive literacy training and discipline saturate all 79 IDEA school campuses in Texas and Louisiana, including the libraries. While the IDEA libraries feel consistent with the rest of campus, they are often different from most school libraries. This isn’t unusual. The libraries at charter schools—when they exist—often reflect the unique philosophy of each school.

Bolstered by school choice advocates at the local, state, and federal level, charter schools have proliferated in the past 20 years. They stand to expand further under Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos. The National Charter School Association estimates that 3.2 million students attended around 7,000 charter campuses in 2017–18. The appeal of charters, for many, is the flexibility to waive certain requirements of traditional schools and embrace varied models, curricula, and educational philosophies, ranging from the rigorous “no excuses” models, with strict dress codes and discipline policies, to Montessori and language immersion. Charters aren’t entitled to facilities funding in most states and rarely have all the features associated with traditional schools—nor are they required to. Most staff, including librarians, aren’t subject to public school certification requirements.

Because campus autonomy is key to the charter philosophy, those with libraries tend to envision and use the space differently. At IDEA Monterey Park, it takes a few months for the youngest students to get used to intensive reading time, IDEA instructor Christina Saucedo says. Saucedo isn’t a certified librarian, but she is the resident AR expert. At first, she says, students have to practice finding their station and getting to work efficiently, respecting one another’s space, and finding books. Students also must find their starting place in the library’s AR system.

Saucedo likes AR, she says, because it keeps students from zoning out on books below their reading level but also keeps them from being frustrated reading above their level. “I’d hate for a student to learn to hate reading,” she says.

When it’s time to leave the library, several children linger with their books. They read library books while walking back to class. Talking isn’t allowed in the hall, but reading is.

At the heart of the charter school movement is the freedom to refocus curriculum and experiment with new school models. This has led public education advocates to raise concerns that charter students are missing out on valuable learning experiences required in public schools. Libraries and certified librarians are not mandatory at U.S. charter schools.

For example, the four Thrive Public Schools in San Diego have classroom libraries—and a small “borrow library” where teachers can check out classroom or small group sets of books for book club and Leveled Literacy Intervention. There’s no certified librarian, but intervention specialist Courtney Ochi says that teachers like the flexibility of their classroom libraries for day-to-day reading, especially in lower grades. These borrow libraries are stocked with grade-level selections across a range of student interests. It’s helpful for Thrive’s personalized, mastery-based instructional approach, Ochi says, “especially in terms of literacy.”

The Thrive administration wants students to have rudimentary library skills. Elementary-age kids at the network’s Comstock campus walk across the street to the public library. They get library cards and make regular trips to check out books. As they get older, they use the public library for research.

|

Martinez (right) with students composing letters to reading buddies at the KIPP University Prep library.Photo by Pablo Cruz, KIPP Texas Public Schools |

Individual missions

Charter models range from open-format schools where students rarely sort into specific classes to campuses where students go through high school with the same 15-person cohort. Many emphasize one subject area, such as science or the arts, while others use novel approaches like blended learning. Others, in an effort to fulfill their “college for all” goals with low-income and minority populations, double down on core academic subjects. The classical approach emphasizes ethical questioning and discussion.

In San Antonio, TX, where charters have proliferated under the auspices of philanthropy, ample space to build, and reform-friendly legislation, individual schools offer insight into the role of libraries in diverse school models. Here, schools serving low-income populations are more likely to invest in library staff and space, knowing that their students might otherwise lack access to this critical resource.

San Antonio charters’ funders include the Brackenridge Foundation and the Walton Foundation. Their growth has been buoyed by champions in the Texas Legislature and a pro-reform state education commissioner.

Compass Rose is one of San Antonio’s smallest and newest models. More established charters enroll some 15,500 students (combined) in the city and receive about 40,000 applications every year, according to Families Empowered, a local nonprofit.

The four campuses of the smaller School of Science and Technology (SST), started in 2005, serve kindergarten through 12th grade with a heavy emphasis on STEM subjects.

Of all those charter networks, only Compass Rose lacks a dedicated library. The school is pressed for space and doesn’t have the funds to stock one. However, Compass Rose founder Paul Morrissey’s “long-range plan” includes a library with books and places to read, Chromebook stations, and flexible seating for group projects. He calls it a Design Thinking Laboratory, reflecting the school’s emphasis on design thinking.

“In order for us to live our entrepreneurial mission every day for our students, it is important that the library is a flexible space that can be used in different ways and to different ends throughout the school day and year,” he says.

Focus on college prep

For other charters, a conventional library is key to their philosophy. College prep–oriented charters such as KIPP and IDEA want students to feel comfortable in every space they might find on a college campus.

The three schools on the KIPP Cevallos Campus serve majority low-income and Latinx populations. Constructed in 2016, the facility provides ample room for library space in each building. In the high school, KIPP University Prep, certified librarian Jennifer Martinez sees library science as critical to the school’s college preparatory mission.

All KIPP University Prep students participate in the research-intensive International Baccalaureate program, requiring a 4,000-word essay. In high school library science class, they learn MLA citation format and research tools. There are some 5,000 catalogued books, plus uncatalogued titles for book clubs and other activities. Martinez uses JSTOR and Google Scholar to teach research fundamentals. She takes students on field trips to university libraries to use larger or specialty databases.

At those libraries, they see college students using the space for individual or group study. Martinez’s students see that “yes, people do use this space,” she says.

She wants students to use the KIPP library in the same way: as a calm place to study alone, or somewhere to meet as a group. For students in low-income homes—85 percent at KIPP University Prep—solitude and quiet can be hard to come by. “It’s a place they can come in and get to work,” Martinez says.

Not all KIPP campuses have such an arrangement. At KIPP NYC College Prep, the library is a flexible resource room, with books—but no librarian. New York City has 236 charters, ranging from Hebrew and Hellenic schools to college prep and Outward Bound schools. Neighborhoods including Harlem and parts of the Bronx are hubs for the ultra-rigorous “no excuses” model.

|

The library at IDEA Monterey Park school in San Antonio.Photo courtesy of IDEA Monterey Park |

From a STEM focus to a classical curriculum

Like IDEA Monterey Park, San Antonio’s STEM-focused SST uses the AR system to organize the library at its Discovery campus, serving kindergarten through eighth graders. Principal Jessica Romero has had to balance competing needs for the space. Like many charters, the Discovery campus building wasn’t designed as a school. It’s an old Albertson’s grocery store.

As the school has grown, administrators have lobbied hard for Romero to repurpose the library, a small, cheerful room lined with bookshelves and tech, overseen by her school’s gifted and talented (G/T) program instructor. She has continually made the case that students benefit from a separate library. “Thankfully, my teachers and the community here support the idea.”

At one point, the administration and board considered an all-digital library. Romero resisted. “Nothing replaces the feeling a child gets when they go get a new book,” she says. About half of the students are eligible for free and reduced lunch, and having books at home isn’t a given for all. Her “new” books are provided by local libraries and Scholastic book fair funds.

Updates to Romero’s SST library include tech for a library makerspace that enhances the school’s STEM mission. A video production area, 3-D printer, and work benches take up one wall. The G/T instructor oversees the makerspace and works with students there. Also, classes make weekly trips to the library, where volunteers usually read aloud to them and help them find and check out books. “The power of a volunteer really goes a long way with a small community like ours,” Romero says.

Great Hearts also relies on volunteers and donations to run the library at its Northern Oaks campus in North San Antonio, where a small percentage of students qualify for free or reduced lunch. The classical curriculum, which emphasizes developing an appreciation of beauty, demands a lot of reading. Classes also visit the library—an open-format area near the school’s entrance—every two weeks to check out books for extracurricular reading.

Students don’t expect to find trendy titles. Great Hearts, with 28 schools in Arizona and Texas, doesn’t allow pop-culture products, artifacts, or discussion on campus, including in the library. Books must have been written at least 50 years ago, with a few exceptions, such as the “Harry Potter” series, which school leaders anticipate will “stand the test of time,” says assistant headmaster Marcy Mitchel.

“We don’t want to settle for the marginal characterization of today’s literature,” Mitchel says. “We want books that enhance our curriculum, not detract from it.”

Washington Latin, a Washington, DC, charter, follows a classical curriculum but doesn’t eschew pop culture or contemporary authors, says librarian Sereena Hamm. “You can view contemporary authors through the lens of deep ethical questions,” she says. “It’s the way of thinking that is the most important.”

When Washington Latin moved into its current building, the library was a top priority. Hamm, who had worked for a public school, wanted to be at a start-up charter to invest in “the long game” of building the library from the ground up. “I noticed that start-up schools tend to not have libraries, at least not soon enough, and I could see what was missing,” she says.

Her commitment has paid off. The space, like many charter libraries, is a little quirky. No longer reliant on book donations, Hamm now has a larger budget for new acquisitions and carefully curates the collection of some 8,500 books.

Still, she says, “You can’t work in a charter school like this and assume you’ll even have what a traditional public school has.”

Bekah McNeel is a journalist based in San Antonio, TX.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!