First Book Studies Add Key Data to Book Ban Conversation

With the release of two educator surveys, the organization provides facts and figures on the detrimental impact of book bans on reading and literacy.

Recent school board and public library meetings discussing specific books in collections have been packed with emotional speeches and incendiary language. Those arguments—for removing or retaining titles—can be very compelling. They capitalize on parental fears or succeed in tapping the empathy of others. But the battle against book ban attempts should be waged from a foundation of fact and statistics, says First Book president, CEO, and co-founder Kyle Zimmer.

|

Kyle Zimmer |

“We should not be making educational decisions, which impact the future of our kids, our communities, and, honestly, our country, based on emotion,” Zimmer says. “This should be a data-driven conversation. That's why First Book has stepped up with these two studies.”

First Book Research & Insights surveyed educators for its Book Bans Impact Study and Diverse Books Impact Study.

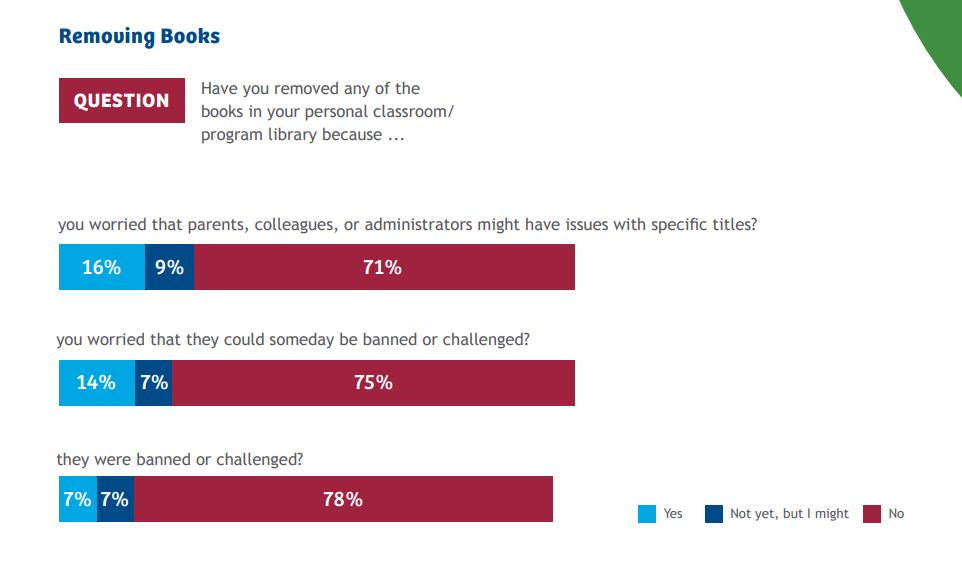

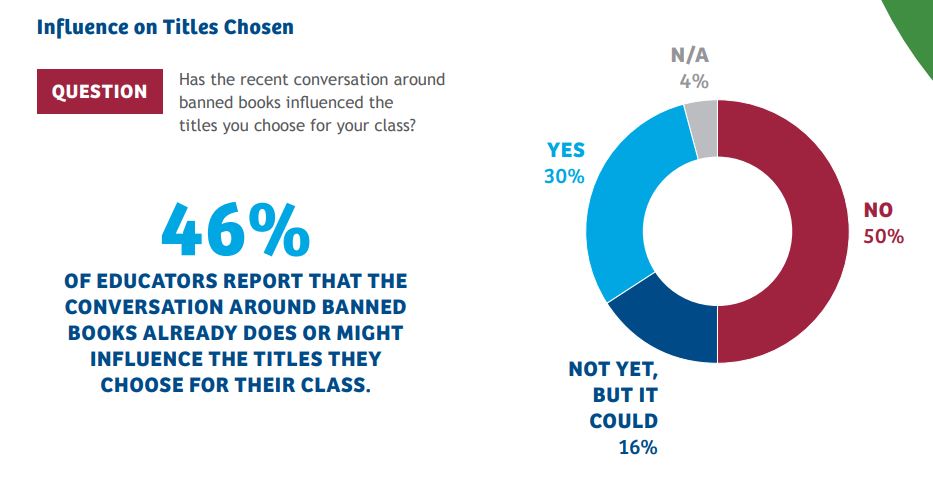

The Book Bans Impact Study, released this week in conjunction with Banned Books Week, surveyed 1,500 school-based educators that included 71 percent classroom teachers and 15 percent librarians among the respondents. Thirty-one percent of educators surveyed said there have been book bans, challenges, or restrictions in their school/district. While only seven percent removed books as a direct result of a challenge, 30 percent said they have removed books because they were worried about a future challenge or that parents, colleagues, or administrators would “have issues with the titles.”

“This was particularly troubling to me,” says Zimmer. “The book bans are having a chilling effect that runs far beyond the districts where the exact ban is in place or is proposed.”

The impact will not only be seen on current collections and students. These responses show that censorship attempts today will have a domino effect on access for future students as well.

Seventy-seven percent responded that they “buy less, control distribution, [and] are more selective.”

Wrote one respondent: “I’m more selective in the books I choose to add to classroom libraries to ensure they are more neutral but still exposing kids to diverse opinions and viewpoints. I’m more careful of ensuring the age ranges of what could be a more controversial topic or view.”

Another said: “I (no longer) purchase books that have been banned or challenged because I worry I am wasting money.”

In addition, 25 percent said they adhere to administrative restrictions for fear of losing their jobs.

“I censor in a way I don’t believe in, based on fear of my upper administration,” wrote one.

[READ: Book Challenges Are Having a Chilling Effect on School Librarians Nationwide | SLJ Survey]

The loss of these books has a negative impact on students’ reading—and most of the titles being removed would fall under the category of “diverse books.” According to the ALA Office for Intellectual Freedom, most challenges were to books written by or about a person of color or a member of the LGBTQIA+ community. And according to First Book’s research, statistics show the critical difference having access to diverse books has on reading. First Book released the results of its Diverse Books Impact Study in September. Key findings include:

- Over the course of this study, collective student reading time increased by 4 hours per week on average after educators added new, diverse books to their classrooms.

- 70 percent of educators reported that their students more often choose books that feature characters that look like them.

- For every 1 additional bilingual book that educators added to their classroom library, student reading assessment scores improved by 7 points on average.

- For every 1 additional LGBTQ+ book that educators added to their classroom library, student reading assessment scores improved by 4.5 points on average.

Any negative impact on reading proficiency, and reading at all, is problematic. The 2022 NAEP Reading Assessment showed the average reading score at both fourth and eighth grade decreased by 3 points compared to 2019 and dropped to 5 and 6 points for the lowest performing students. Thirty-seven percent of fourth graders performed below NAEP’s proficiency level.

“In the face of this forest fire of a literacy crisis, we are doing something that undercuts the teachers and undercuts the kids in their engagement in reading,” says Zimmer. “The consequences can be catastrophic.”

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!