Let’s Talk About Poverty: 10 Policy Ideas to Support Vulnerable Students and Eliminate Stigma

How can schools and their library programs buffer the effects of poverty and economic hardship? Here are original, crowdsourced ideas from across the nation.

|

Illustration by Anna Godeassi |

|

Related Article: |

Poverty is a complex term often discussed in professional development workshops, student intervention meetings, and school data reports. Outside of these contexts, poverty is deeply personal, a topic that can be filled with shame and stigma. At the start of the pandemic in March 2020, I had an opportunity to read Rex Ogle’s memoir, Free Lunch, about Ogle’s family struggle with poverty during his first year of middle school. As I sat in my living room devouring page after page, Ogle’s story triggered a deep reflection of my own secondary school years. I admired Ogle’s vulnerability as he shared his experiences. I began to wonder how I carried my own experiences with economic hardship and if I could achieve a similar level of freedom by destigmatizing poverty discourse and talking more openly.I also began to think about the parts of my story that I would like to share, and how I could model compassionate dialogue with middle school students.

First, a few facts. Eligibility for government programs is defined by poverty guidelines that are used by the Department of Health and Human Services, and the poverty determination varies by person according to factors such as the number of household members, state residency, and before-tax or after-tax income rules set forth by individual agencies. According to the 2021 guidelines, a family of four with an income below $26,500 is living in poverty.

Poverty does not have clear-cut parameters. One family might qualify as living in poverty, while a family making a few hundred dollars more does not. Here, I will use the term poverty to describe those qualifying through government guidelines and economic

hardship to refer to those in the range slightly above that figure. Both are parts of a spectrum.

Living in poverty often means an intense struggle for the basic survival needs of food, shelter, and clothing. Living one step above that might not qualify as poverty by the government, but it may not be very different. One might say economic hardship is just as intense to the child who is living it. Within that range, a family might suffer a loss of employment, creditors calling, abrupt relocation, or other destabilizing events. It may have the look of an attractive home in the suburbs that is one missed payment from eviction or a foreclosure notice.

During the pandemic, I often found myself wondering how my family would have survived. Both my parents worked in the service industry with positions in the restaurant and bakery business and, later on, a gym and sports complex. Would we have lost our apartment? Thinking back, I realize that my entire family was living under a great deal of stress, but I did not fully perceive it at the time.

My family did not have health care. We did not get annual flu shots. We used the emergency room if we were in extreme medical need. My family faced an unemployment crisis when one of the restaurants closed and a health issue began to impact one of my parent’s physical mobility. At times, my parents worked seven days a week and more than one job. We rented a one-bedroom apartment and occupied it as a family of four. Black mold was a recurring housing issue that was not properly addressed. When our kitchen sink plumbing failed, my father ingeniously replaced our disintegrating metal pipes with sawed-off detergent bottles that he connected together to fashion a plastic pipe. It lasted for several years.

On the flip side, my mother always found a way to get us to an annual dental preventative visit even if she had to save in advance for it or skip her own care. We all had public library cards and often found our local branch was the only place to go on a hot summer day to relax, read, and enjoy air-conditioning! In high school, my sister and I qualified for free and reduced lunch. Senior year, I received several college application waivers.

Many may wonder, why didn’t we file a complaint? Why didn’t we move? Well, our neighborhood was a safe, low-crime area. We were within walking distance of a bus stop, a train station, a supermarket, and a laundromat, and we were living in a rent-controlled space. That may not be the point. One way to destigmatize poverty is avoiding judgment of another family’s decision-making.

Financial instability feels like a balancing act performed with a highly critical audience that often includes the self. It is so easy to judge another adult’s decisions and make generalizations about what they could be doing to improve their life. Don’t judge the new sneakers. Don’t judge the expensive phone. You have no idea of the backstory.

Destigmatizing poverty among middle grade students is important. During adolescence, students move toward identity formation and become more self-aware. Suddenly, comparisons among kids’ clothing, housing, and other factors may become more pronounced. At the same time, school-level dialogue about economic hardship often declines with school pantries and food backpack programs terminating at the end of elementary grades. Even if schools experience a reduction in the number of applications for free and reduced lunches, poverty doesn’t end as students enter middle or high school.

While librarians cannot take on or solve all the issues involving poverty and economic hardship, we can create policies that, at best, help vulnerable students access materials and their school environment; and, at the least, do not shame them. So what are school library programs and other school-wide initiatives doing to buffer the effects of poverty and economic hardship? Here is a list of original ideas and crowdsourced information from colleagues and librarians across the nation.

|

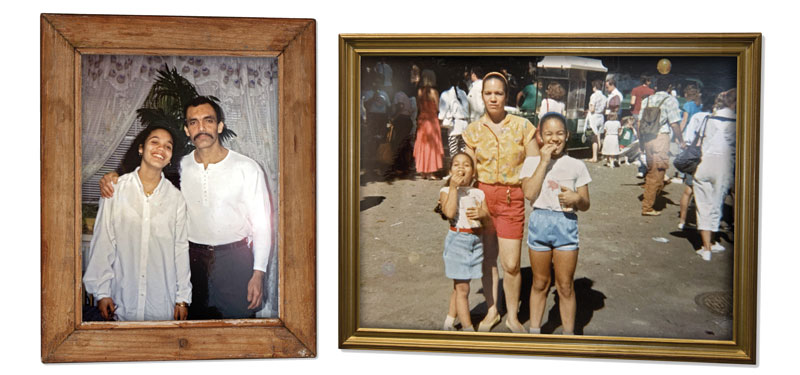

The author with her father (left) and with her mother and older sister at the Central Park Carousel.Family photos courtesy of the author |

Eliminate late fees. If your program prevents students from checking out books because of lost or late items, reconsider your policies and look for alternative methods to encourage returns. Would you really penalize a student if you knew the student was experiencing housing insecurity or genuinely could not afford to pay for the materials?

- Can you find different ways to replace lost items?

- Can you refocus and see lost books as well-read books that remain in permanent circulation to a wider audience?

- Can you admit that lost books are simply a reality in a lending business?

Alternatives to late fees include:

- Focusing on collective efforts that spotlight the number of returns from specific classes or grade levels.

- Writing a special grant to fund the replacement of lost books.

- Asking your administration to support more equitable policies by providing an annual lost book fund to cover a percentage of losses.

Reconsider discourse that emphasizes financial comparison and need. For example, avoid asking what types

of gifts students received for a holiday or birthday.

Organize a school pantry or snack station. These can be stocked through a community food drive, PTO support, Amazon wish list, or community grants or by coordinating with a local grocery store to sponsor customer donations.

Start a cafeteria recycling or share table for prepackaged items from meals that students did not open.

Begin a Library of Things that loans untraditional items. This is something I’ve tried at both middle and high schools. Solicit suggestions from your student library council. Items may include necessary supplies or those that enrich extracurricular experiences and work toward reducing the achievement gap: a wireless mouse, origami kits, Micro:bits, Raspberry Pi with a book on coding, calligraphy kits; bullet journal kits with a guidebook, markers, and stencils. Take-home kits may include reading materials with each item.

Offer a personal care zone. Using the same concept as a Little Free Library, schools can create a station offering trial-size personal care products. These might include deodorant, soap, shampoo, conditioner, feminine products, individually wrapped breath mints, hairstyling products, toothbrushes, toothpaste, Q-tips, etc. Students and teachers can donate materials, as well as use products. Consider a discreet location such as the restroom or school nurse’s office.

Work with your technology team to offer Wi-Fi hotspots. Since this is a huge endeavor, your initial efforts might include collecting articles and information on how other school divisions implemented such programs and how school libraries managed them. These can inform tech team planning for this type of student support. Every small step toward change counts.

Work with supervisors and explore expansion of library services. Research models such as Nashville’s Limitless Libraries Model, which automatically provides students with access to the public library and school-based delivery of materials. Present these options to library supervisors. If a locality and school division are not ready for this level of collaboration, explore alternative steps on the way to this goal. This might include facilitating library card applications, virtual visits or book talks, or an in-house kiosk to place public library materials on hold.

Consider an open-ended field trip form that allows families to pay fees and include the option to donate one or more trip fees for other students.

Make a consistent effort to booktalk titles that deal with issues of poverty and economic hardship. Model respectful discourse. The goal is not to get students to divulge personal information but rather discuss a taboo topic in a way that builds broader acceptance. It may be helpful to discuss titles using Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop’s concept of windows, mirrors, and sliding glass doors. Ask open-ended questions: Was this book a mirror or a window experience? Ask students to personally reflect in a manner that does not require public sharing. The act of self-reflection alone is powerful.

With many families facing food insecurity, unemployment, eviction, and displacement, it is important to routinely engage in conversations surrounding poverty and economic hardship. When we remain silent, experiences and identities remain invisible and opportunities to model empathy are lost. At the same time, librarians must manage a delicate space and recognize that not every student in poverty wants to read a book that amplifies stress. Sometimes readers need a completely unrelated reading experience to escape these triggers. See the accompanying booklist for titles that include story lines about poverty as well as those that provide absolute escape.

Librarians have the power to design an understanding school experience that responds to the stress of economic hardship. What does your program communicate to students? Is it inclusive of all backgrounds, including those students facing some version of financial upheaval? Ultimately, I want my program to say that no matter what is going on in your life, we’ve got you covered.

Monica Cabarcas is a middle school librarian in Charlottesville, VA, and a reviewer for SLJ.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!