First-Person Graphic Memoirs Bring Events to Life for Students

Few statements are as compelling as “It happened to me.” These powerful graphic novels convey that message.

|

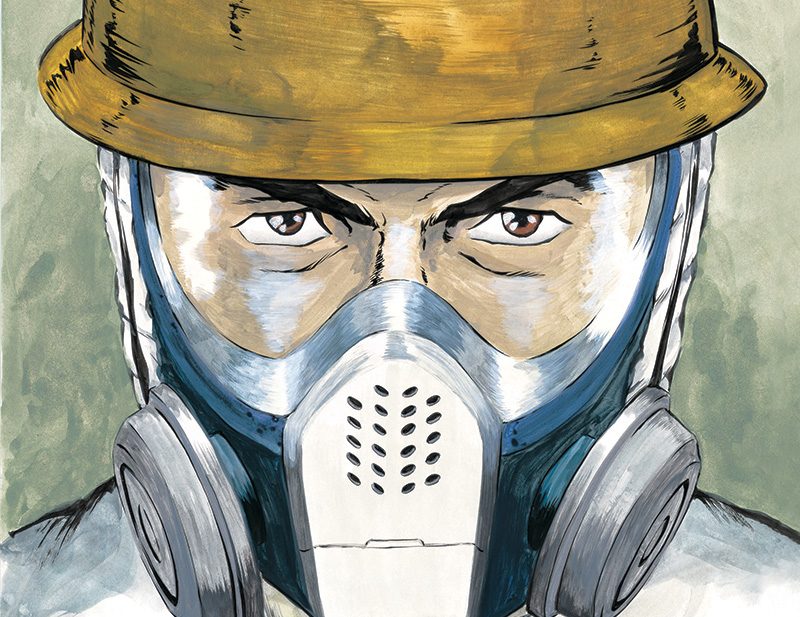

Illustration from "Ichi-F" ©Kazuto Tatsuta/Kodansha, Ltd. Reproduced with permission. |

Related article:First-Person Graphic Memoirs: 17 Recommended Titles |

There are few statements as compelling as “It happened to me.” Increasingly, that’s the message that many powerful graphic memoirs convey. Recent classics such as Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis and Rep. John Lewis’s “March” trilogy, cowritten with Andrew Aydin and illustrated by Nate Powell, bring readers to the front lines of historical events, showing how ordinary people respond to extraordinary times.

These creators not only humanize history but also present a vivid, full picture for contemporary readers, providing details and putting events in context. The best of them wrap a history lesson in a good story, allowing readers to live through history alongside the creators.

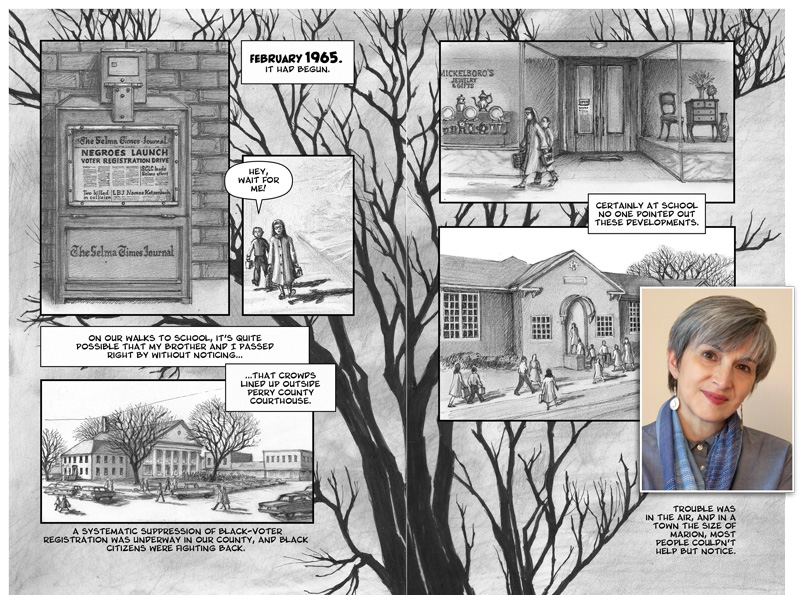

Take, for example, Darkroom: A Memoir in Black and White, in which Lila Quintero Weaver depicts what it was like to grow up in Marion, AL, during the civil rights movement. Brigitte Findakly recalls a childhood punctuated by revolutions in Poppies of Iraq, her story of growing up in the city of Mosul. California native Brian Fies chronicles the loss of his house, neighborhood, and almost all his belongings in A Fire Story, bringing in the accounts of other survivors to tell the story of one of the largest wildfires in that state’s history. Each of these authors tells their personal story while adding texture and nuance to the often dry facts of history.

|

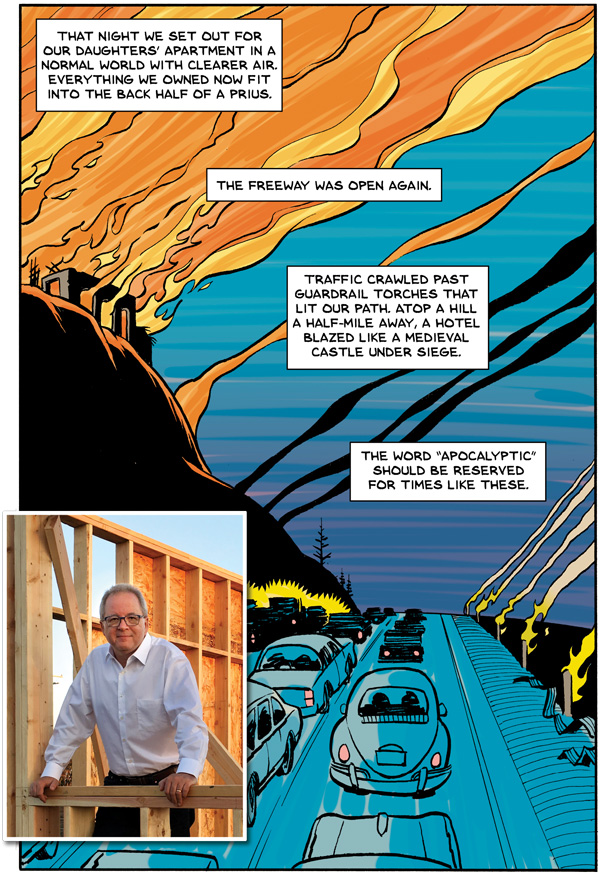

Brian Fies (inset) chronicles his and others’ experience of California’s massive 2017 Tubbs Fire in "A Fire Story.""A Fire Story" page art courtesy of Abrams ComicArts; photo by Karen Fies |

Historical connections

In the classroom, graphic memoirs provide vivid portrayals of history. Teacher Tim Smyth uses the online comic Madaya Mom (ABC News, 2016) in his 10th grade modern global history course at Wissahickon High School in Ambler, PA. Smyth first has his students research the history and current situation in Syria. Then they read the comic, which is based on actual text messages sent by a woman trapped in the Syrian city of Madaya.

“The discussion changes, as these events are no longer about a far-off land with nameless and faceless people,” Smyth says. “The students get to know an individual family’s struggle to survive, and they immediately begin to make connections to the Holocaust and other genocides we have discussed and researched throughout the year.”

Smyth also uses the “March” trilogy and the first volume of “Barefoot Gen,” a manga series written by a survivor of the bombing of Hiroshima.

“We teach ‘Barefoot Gen’ as we learn about World War II and the often overlooked postwar impact,” he says. “The students read Slaughterhouse-Five in ninth grade, and we are able to make direct comparisons to the firebombing raids on Nazi Germany and the two atomic bombings of Japan.”

“ ‘Gen’ gets into Japan where the textbook leaves off—the story of how the Japanese people were left largely to their own devices following the bombing,” Smyth adds. “Gen [the character] loses almost his entire family and is forced, at a young age, to take on the role of caretaker for his mother and newborn sibling. It is a heartbreaking story, but also one of inspiration that leaves students questioning the role of these bombing raids in World War II.”

While textbooks, maps, and photos can convey factual information about a period or an event, graphic memoirs put readers inside the scene and emotional moment. In Darkroom, Weaver shows the social norms of segregation, on the street and in her school. After her school was integrated, tension lingered. Weaver, who had emigrated with her family from Argentina to Alabama in 1961, was something of an outsider in the Jim Crow South, where she was usually treated as white. She shows a black student telling her, “We don’t need you, soda cracker. Go back to your own kind! You are not one of us!”

In A Fire Story, Fies depicts neighborhoods reduced to ashes and twisted metal by the 2017 Tubbs Fire, then the most destructive of the California wildfires to date (it has since been eclipsed by the Camp Fire of 2018). California fires have been getting more destructive each year, and climate scientists maintain that climate change is responsible.

One sequence shows Fies standing in a store, unable to remember whether he still owns a watch. “It’s meant to be kind of cute and funny, but it’s also evidence of what we call ‘ash brain’ around here,” he says. “You don’t remember things, you lose track of events, your memory is bad. For five minutes I couldn’t remember if I owned a watch, and that’s a very strange mental space to be in.”

He included stories of other survivors as separate sections throughout the book. “I realized that all the people I knew, the neighbors who lost their homes, we are all middle-class, and we come from similar backgrounds,” he says. “So I deliberately set out to find people from different backgrounds—someone who was richer than I was, a few people who were working-class, a very poor elderly woman. I wanted to provide as broad an overview of this disaster as I could.”

|

"Poppies of Iraq" by Brigitte Findakly, illustrated by Lewis TrondheimPage art courtesy of Drawn & Quarterly |

Character connection

Graphic memoirs set in the creators’ childhood and teen years, such as Persepolis, Poppies of Iraq, and Darkroom, can be particularly relatable for students. “I think that most of history, and psychology, focuses on ‘old’ people, in the sense that notable people are recognized in the later years of their life,” says Jason Nisavic, who teaches psychology and U.S. government to grades 11 and 12 at Alan B. Shepard High School in Palos Heights, IL. “Whenever we focus on younger people, especially the rare teen or preteen who pops up, interest noticeably increases. That’s one reason why Persepolis in particular is so relatable. Students can ask themselves, ‘What was my life like at 10 years old?’ The story can spring to life in their minds.”

Another powerful draw: a scene that would take a whole page to describe in words can be portrayed in a single graphic memoir spread. This is particularly important for those set in an unfamiliar time or place. In Ichi-F, author Kazuto Tatsuta walks us through the details of his job as a cleanup worker at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, which was destroyed during the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan. He shows the many pieces of his hazmat suit, the different areas of work and relaxation for cleanup workers, and the twisted wreckage of the plant itself from many different vantage points, helping readers to grasp the situation as a whole.

While pictures may draw young readers in easily, it’s vital that visual information be accurate. “The details don’t have to be spelled out, but they also often have to be even more accurate than prose,” says Smyth. “When drawing images about historical events, it’s so important to get all the details correct, whereas in prose, a few sentences can be written and the rest left up to the imagination of the reader.”

|

Lila Quintero Weaver (inset) portrays civil rights struggles in Marion, AL, in her memoir, "Darkroom."Darkroom: A Memoir in Black and White ©2012 Lila Quintero Weaver, published by the University of Alabama Press. Inset: courtesy of Lila Quintero Weaver |

Research matters

Memoirists often conduct research, and many cite their sources in an introduction or bibliography. Fies started planning his graphic novel about the fire that destroyed his home almost as soon as it happened, so he began researching right away. “As I was walking back into my burned-out neighborhood, I was taking pictures and making notes knowing that I was going to be writing and drawing about it later,” he says. He studied maps and official reports about the fires so he could make sure his facts were right.

Detailed research also enabled Weaver to include an important sequence in Darkroom that she didn’t witness, and of which no photos have survived: the 1965 voting rights march in Marion that ended with a white state trooper shooting a black man, Jimmie Lee Jackson. Weaver’s father was there with his camera, but the white people who attacked the black marchers attacked photographers as well.

“One of my inspirational sparks was the fact that there were no photographs of that night, no visual documentation of what happened, because the white mob that was there had as its goal to make sure that didn’t take place,” Weaver says. “I wanted to create from my imagination a replacement from that void.”

While many historical narratives provide the “who,” “where,” and “when” of historical events, graphic memoirs focus as much or more on the “how,” “why,” and “what.” This presents a richer picture of a culture and the way it is disrupted by war, revolution, economic shocks, or catastrophic natural events—and makes it easier for readers to connect.

“Teens go through similar issues across time, and these comics help reinforce [that],” says Smyth. “In Persepolis, [the lead character] just wants to be herself, dress the way she wants, and listen to the music she likes. I connect to these issues as well, and that helps me [relate to] my students.”

Brigid Alverson edits SLJ’s “Good Comics for Kids” blog.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!