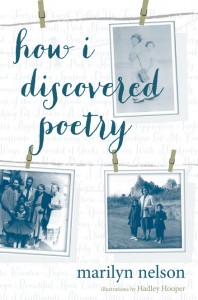

How I Discovered Poetry, Marilyn Nelson, illustrated by Hadley Hooper

How I Discovered Poetry, Marilyn Nelson, illustrated by Hadley HooperDial Books, January 2014

Reviewed from final copy

Marilyn Nelson, author of the 2006 Printz honor book A Wreath for Emmett Till, is responsible for what may be this year’s most unique contender, pairing two genres only occasionally spotted in the YA world — memoir and poetry — to make a whole that is notable and worth recognizing.

Memoir is a tricksy genre for a literary award. Like all nonfiction, the first line of assessment is usually accuracy — and a memoir that is too perfectly literary these days may raise suspicion of creativity, which isn’t always desirable in nonfiction. Nelson neatly sidesteps the risk of sacrificing beauty for truth (despite what Keats claimed, literal truth isn’t always lovely) by supplying only tiny fragments, snapshots in poetry, of a fascinating childhood. The poems are filled with facts of time and place and happening, but more than anything they are about the emotions of the moments collected, a decision made clear in the afterword where Nelson explains that the poems are not entirely memories; research and imagination have played a part as well. And the most important accuracy, emotional accuracy, rings loud and clear in every poem.

The bare facts: Nelson’s childhood would probably make an excellent novel based on what I gleaned from this text (I could look for corroborating data on Wikipedia or elsewhere, but I’m going to let the book stand on its own). The daughter of one of the first black career officers, she spent her childhood in the 50s moving from base to base, often the only black child other than her own sister. It seems, from the portrait in her poems, to have been strangely idyllic in many ways; despite the strong racial tensions of the decade, army base life’s rarified environment and officer-based pecking order allowed her to come of age standing slightly sideways from some of tensions between blacks and whites in America. She was a novelty to be treasured rather than an other to be scorned for much of her childhood. And while any kind of othering leaves its mark, she was able to form herself in a vacuum that allowed her to be a poet first, defined by passion at least as much as by skin color.

But it wasn’t a fully sealed vacuum, and the dichotomy between her life and the life outside the base looms large in the collection. The poems range from the deeply personal to the largely historical, many of them anchored by repeated images — “Making History” and “First Negro,” the speaker’s dark skin juxtaposed against white classmates and friends, misheard or interpreted information, and moving, always moving. Often what isn’t said or recognized by the speaker is critical, as in “Queen of the Sixth Grade,” where the speaker and her friends punish a new classmate for saying “that name / she learned in some civilian school down South.” We can imagine what name it was, but the specifics are never stated outright, making the reader complicit in understanding rather than a passive receiver of the author’s thoughts and words.

There are only 50 poems here (take away the illustrations and this would have been thin even by chapbook standards), all unrhymed sonnets. The sonnet form means they are brief, which again speaks to the importance of what isn’t stated — Nelson uses her 14 lines and the silences and unspoken connections the reader can make to craft a story far larger than the number of words. The form works well here; sonnets have a rhythm that makes each word drop like a stone into water, which is very effective; these sonnets often don’t have the twist at the end that Shakespearean sonnets always include, but the fragmented recollections and incidents carry plenty of weight without that. Rhyme would have risked losing meaning to the beauty of the language, so the form suits the subject perfectly, although I don’t think it’s the only poetic form that might have worked (unlike Wreath, where the form was part of a larger metaphor about remembrances and no other form could have been used — a point I make not as a comparison but to illustrate the way that sometimes form in integral in poetry and sometimes it’s not). I’ll be interested in hearing other opinions, though, because poetry is so divisive.

Finally, let’s touch on the illustrations, because design is one of the characteristics listed in the P&P and it’s clear that thought went into the design here. The illustrations are simple drawings floating in the white space surrounding the poems, old-fashioned callbacks to the days of 2-color separations, with the colors not always perfectly lined up within the outlines, when the outlines are present — think Dr. Seuss, but without the whimsy. Hand drawn, most in a soft blue with black lines (some have more colors, mostly brown and gray, but keep that old style look), they suit the setting well and sometimes serve to ground readers in the subtleties of the poems — one poem that ends with the speaker’s mother crying “My God! Your hair!” has an illustration of the back of a girl’s head with her (unprocessed, all natural) hair as the focal point. Only one poem changes the visual style — “Darkroom,” fittingly, is illustrated with photos (actual archival photos of Nelson’s family, an image used in slightly altered form on the cover), but the photos are washed in blue and hanging on a handdrawn line so that they seem in keeping with the rest of the collection.

(And as long as we’re on design, the paper stock is really nice; this was a physically satisfying book to read, despite its slim size.)

So where does this fall in terms of Printz potential? There’s a lot packed into a small package, but a text that can be read in only an hour or two might seem too ephemeral despite the weight of the ideas explored. Also, there’s bound to be an age question: is this YA? It flows from age 4 to 14, making it appear to skew slightly young, although it’s about the adolescent journey so it’s really not young at all. It’s a genre blender — poetry, memoir, and history, plus illustrations that enhance the whole — and those have historically fared well. If this picks up an honor I won’t be surprised at all — but I don’t think it’s a sure bet either. What say you?

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!