Zines: Cut-and-Paste Publishing by and for the People

Zines spotlight voices, opinions, and histories often missing from mainstream publishing. Here's what you need to know about curating, collecting, and creating these works at your library.

|

Illustration and SLJ March cover by Mark Todd |

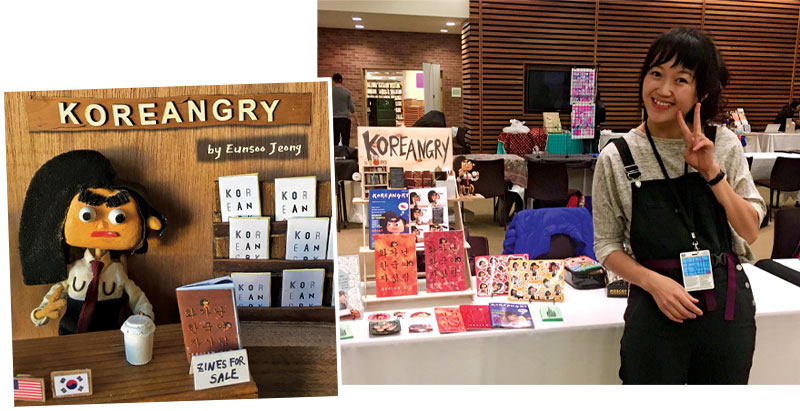

KOREANGRY —It was hard to miss the zine’s title or the crowd packed around the creator’s table at the Portland (OR) Zine Symposium. People snatched up multiple copies of the self-published, full-color little magazine, illustrated with handcrafted dioramas starring a foul-mouthed Korean girl. The righteous anger of creator Eunsoo Jeong’s self-proclaimed alter ego animates her as she expounds on racism, Korean culture, and girl angst.

|

Related Articles9 Books about Zines for Teens and Tweens |

The zine and its accompanying sticker sheet of exclamations in English and Korean—including Yaaas Queen!, OMFG, SHUT UP—as well as mason jars of kimchi on offer, sold out the first day of the show.

Everything about this vivid zine—its DIY origins and stupendous creativity, cultural authenticity, and over-the-top emotion—make it a magnet for young readers, and a great way to introduce zines to teens. The format invites discussion about how the zine was made, while its content provides examples of howto address racism and anger with humor and creativity. It belonged in my public library—and a school library. I could picture kids who never read, reading it.

As a former public library outreach librarian, author of graphic novels, and zinester, I love zines. I’ve shared appropriate zines with kids, included zines in materials my library sends to classrooms to augment school libraries’ offerings, led zine-making workshops, and published zines myself.

Nothing about zines is standard—but that’s the whole point. A zine is a self-published or indie publication, birthed with a do-it-yourself ethic. The word zine comes from the word fanzine (itself derivative of magazine). Zines are generally idiosyncratic, have small print runs, a low budget, small distribution, and may exist totally outside of mainstream culture and readership. They come in an array of shapes and sizes and publish irregularly, and they are made by creators who publish for the love of it, not fame or money.

There’s an astonishing array of sizes, formats, and topics. Examples of recently published zines include: A teen’s personal account of being hospitalized for depression. A compilation of work by and about the Diné/Dineh/Navajo and their ongoing efforts to preserve their culture. A collection of writers’ flash fiction about the moon. A self-help manual for Black women. A biography of the musician Prince. Tips to detox your masculinity. A comic about gender surgery. Reviews of different kinds of pencils. A tour of Asian food carts in your town. Self-defense for trans women. A mushroom journal field guide. BIPOC experience of going to art school. A history of Chinatown, in your city. A guide to silk screening. A collection of fictional lore about bugs.

Intrigued? Immerse yourself in the world of zines, including tips on library purchasing, cataloging, and circulation; zine making with students; resources; and a brief history of the medium.

|

From left: A display at the San Fernando Zine Festival;Zine creator Eunsoo Jeong at the Toronto Comic Arts Festival.Courtesy of Eunsoo Jeong |

Zine making: exuberant expression

Zines not only inspire kids to read; they inspire kids to make zines themselves. I find student zine workshops to be liberating and exuberant. Making zines is inherently different from typing an assignment on a computer, or commenting on social media, because it’s analog and physical: You cut and paste, you hand write, you draw. You are choosing the content and creating the format.

Zine making prompts kids to collaborate, share, and comment on one another’s work while creating, wherever it happens: in classrooms and libraries, with kids learning remotely, in health facilities, or in juvenile detention centers. Whether the kids are labeled as artistically gifted or having a disability, positive feedback from teachers can affirm their excitement about self-expression and self-empowerment. There’s a hum of classroom activity, the buzz of being in the creative zone, and usually a request for more zine-making time.

Freed from the constraints of essay formatting, spelling, and rules, kids’ creativity blossoms. Examples: A male student with a passion for Norse mythology filled his zine with captioned drawings of Norse deities. A middle school girl, angered by the lack of positive Black fashion and beauty advice in the media, collected scant Black images from mostly white fashion magazines and collaged them into her glorious zine, Rich, African, Beauty, Black, Natural Radiant; My Black Is Beautiful.

|

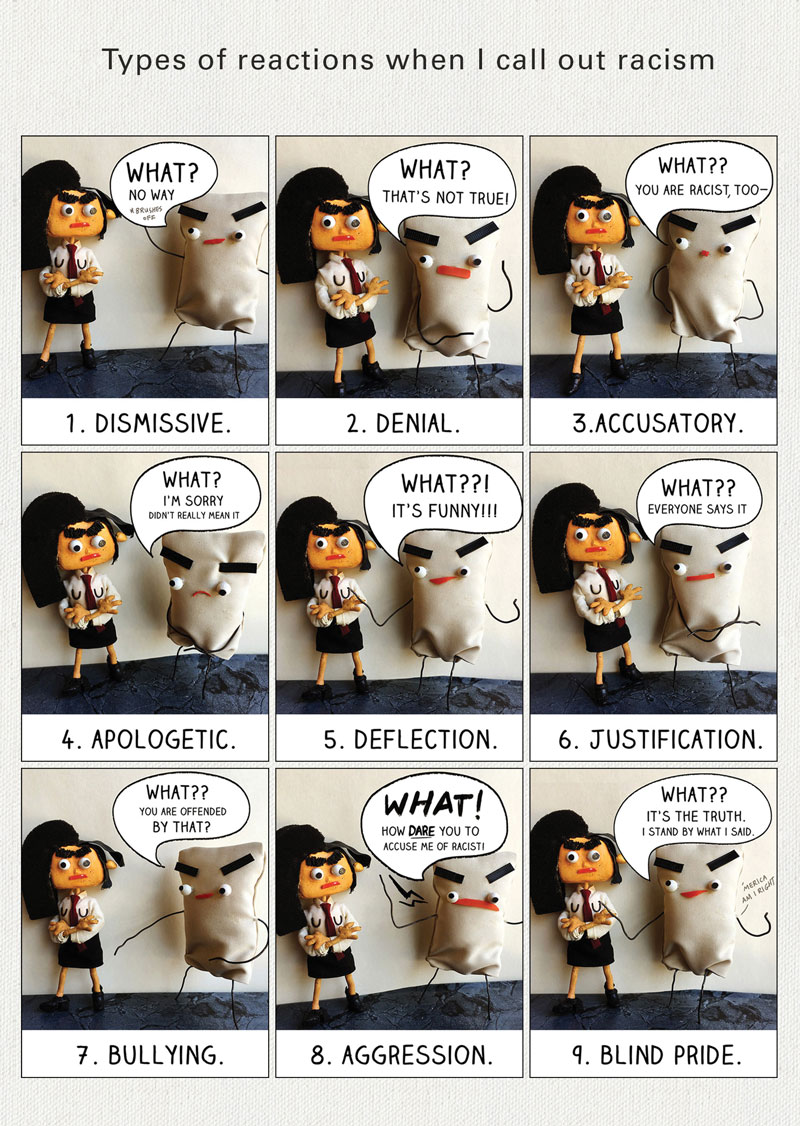

Issue #7 of KOREANGRY |

A young comics fan cut out people’s heads from magazines and pasted them on bodies he drew in a speeding convertible, racing through town. The top hat was flying off the driver. “That’s the mayor,” he explained.

Zine making can also bring out the brilliance in kids with no desire to draw or write. An autobiographical zine, This Is About Me!, by a middle school boy, featured just adjectives clipped from magazines, and his handwriting. “I’m MARVELOUS! And PRICELESS. Also ART-istic. Don’t forget BEAUTIFUL!” the zine proclaims. “I’m very FUN”—readers could hardly disagree—and it concludes “I’m also SPECIAL and EXTRA ALIVE.”

Including zines in your library can fill holes in your collection by representing marginalized, unedited voices and sharing unique views on topics mainstream publishing (and the internet) don’t cover. The zines I purchased for my public library in Portland, OR, provide unique information from outside the history books; in this way, the format empowers overlooked narratives. Teachers often requested library materials on local topics absent from their school collections, such as Portland’s BIPOC or ethnic neighborhood history. Zine-makers’ approaches to such topics differ greatly from standard historical records my library has on the city’s racial and ethnic demographics. Those focus on white “settlers” and offer dense, dry reading not intended for or appealing to students.

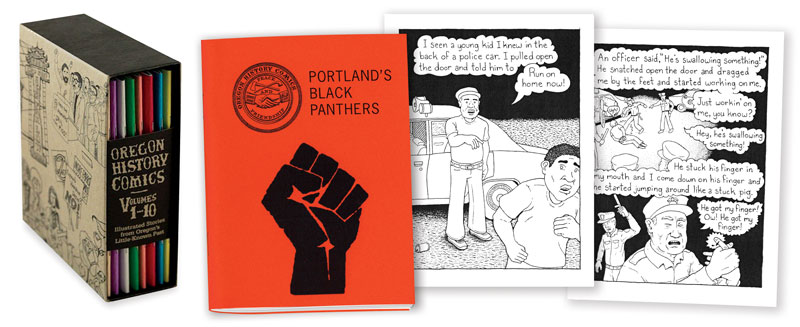

Many zines’ micro-historical topics are geographically specific. A stellar example was a series of small zines about Oregon history, organized in 2009 by Sarah Mirk, a Portland journalist, cartoonist, and zinester, with Portland arts nonprofit the Dill Pickle Club (later known as Know Your City, but now defunct), which published the series. Together, they picked 10 topics to cover; Mirk chose Portland artists to illustrate them.

“There are two things I love about this project,” Mirk said in an interview on the site of Gridlords, a comics publisher. “First: Writing a script, then handing it over to an artist who turns my story into something completely different.... Second: Many people have told me that they enjoyed reading the comics. It’s great to create something people love to read and hold.”

The series, out of print but downloadable from Mirk’s site, includes titles likePortland’s Black Panthers, The Lives of Loggers,The Streets of Chinatown, Portland’s Dead Freeways, and The Vanport Flood, about the 1948 flood of a historic Black neighborhood. Most were kid-accessible histories where no others existed. I sent these to schools so often; library copies went missing. These works inspired kids to rediscover lost cultural histories and shared the fun and importance of doing original research.

Enhancing your collection

“Zines expand the voices and points of view represented in the library,” says Jenna Freedman, director of the Barnard College Zine Library in New York City, who called the format an “equitizing platform.” She adds, “I think of zines as an everygrrrl medium: It’s important to understand and remember the experiences of everyday people to tell the stories of our lives.”

In this way they serve to decolonize your library by equitizing the bureaucratic, top-down way information is written, published, and packaged, and even flip how library content is purchased. You might, for example, have students assist you in choosing zines from zine fests and distros.

For librarians starting a zine collection, Freedman recommends checking out the Zine Librarians Code of Ethics, which she calls a tool for acquiring, managing, preserving, and making accessible zines in a library setting.

The school library is a great place to circulate student-created zines. Bear in mind, though, that while kids love making zines, they don’t always like reading zines by other young people, due to the lack of narrative and coherence in kids’ writing. Still, having their work in the collection and the catalog can be thrilling for young creators.

|

The “Oregon History Comics” series, organized by Sarah Mirk, includes Portland’s Black Panthers by Mirk with art by Khris Soden.Courtesy of Sarah Mirk and Khris Soden |

Purchasing tips

When buying zines for your collection, check your library’s selection policy and update it to include zines. Write an update that provides guidelines for future purchasers, and so you can defend your purchases if they are challenged. Also include physical limitations of what fits with your collection.

An example of a written policy: “Zines are included in this collection as a reflection of the community’s creation and creative history, to broaden our collection of indie and small press publications, and to cover trending topics such as transgender health, local BIPOC culture, and DIY culture not covered by mainstream press.”

Be aware that zines with multiple small pieces are costly to catalog and maintain.

The best resources for purchasing zines are zine/mini-comics fairs, distros (zine distribution shops), stores that carry zines, Etsy, and zine creators themselves. If you lack zine resources locally, you can still order online from distros and bookstores. Also consider buying zines when you travel to larger cities or attending a zine fest such as the Zine Pavilion at the annual ALA Annual Conference.

Online resources include Microcosm distro’s list of zines for teens, aimed at matching possible curriculum or teen-related topics, and Zinelibraries’s list, targeting younger readers. Remember that people who sell zines may not have experience with kids and could struggle making kid-appropriate recommendations. Expect you’ll have to vet zines to meet your standards.

“We get this question a lot: ‘What zines should we buy for my classroom/library/after school program?’” says Joshua James Amberson, founder of Antiquated Future distro in Portland, OR. “Educators need to preview everything,” he advises. “Zines can be very text heavy, and it’s hard to know what each educator considers kid appropriate.”

When acquiring zines created by youth under 18, you may need consent from the child creator, their parent/guardian, and the school, to share them or add them to your collection. Like social media, zines are a form of publishing; once something is out in the world, it’s hard to retract.

More insight while purchasing

Zines and zine providers change constantly, so every zine shopping spree is a new adventure. Expect to be thrilled by what you can get and frustrated by what you can’t.

At zine fests, zinesters tend to take cash or credit cards or use venues like Venmo. Work out in advance what library spending approvals are needed and how you will pay for zines.

It can be difficult to learn much about the identity/age of zine creators. Most commercially available zines are created by folks ages 20 and up. Zines can be anonymous or written under pen names, with little biographical information about the creator.

Zinesters make little money, so, when possible, buy directly from them, as distros and bookstores take a cut. But buying from distros and independent books stores help them survive too.

Consider the “five-minute rule” when trying to choose a few works from a sea of zines. Generally, if it doesn’t connect with your collection needs or grab your reading attention within five minutes, it probably won’t hold your readers’ attention either.

COVID-19 impact

Russ Johnson, zine librarian at Hennepin County Library in Minneapolis, MN, says that acquisitions are more challenging since COVID-19. Before the pandemic, the Twin Cities Zine Fest featured over 100 zinesters on its site, making purchasing and networking easy. Since then, many in-person fests have been canceled or scaled back. Johnson plans to reach out to smaller fests and individual zinesters to try and reconnect.

On the production side, access to color printing (via color photocopying and Risograph printing) means more high-quality color zines, but also a rise in pricing: The average zine cost is now $5 to $10, not $1 to $5.

|

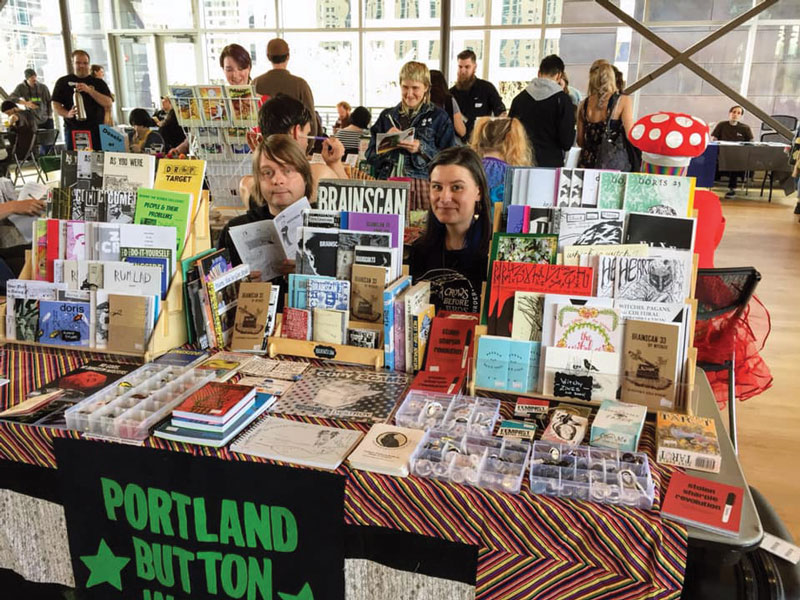

Alex Wrekk (right), creator of Stolen Sharpie Revolution and the zine BrainscanCourtesy of Alex Wrekk |

Cataloging, promoting, and shelving

Since kids love having short, entertaining content at hand, some libraries have zines available as an uncataloged browsing collection. If you decide to catalog, do it in a way that the information is accessible. Cataloging zines recognizes these works as equally important as the rest of your collection. But classifying all zines under the subject “Zine” does little to meet the various needs zines can address. Subject access is crucial, and sometimes needs to go beyond standard subject headings.

Specific subject access is even more crucial for hard-to-find or potentially controversial information, like teen transgender healthcare, which gets lost under a broad subject heading like “Health.” In another example, adding the subject “Latino History–Modesto, CA” might connect a history teacher looking for Californian BIPOC history to a zine they can use.

If you’re stuck with standard subject headings or a reduced form of cataloging with no headings, consider adding a sentence or two of description to the catalog entry, such as “This zine explores African American restaurants in Atlanta, GA.” Or, add tags if they are in your catalog.

The description, or tag choices, are best if created by, or with input from, zine library staff. That way, catalogers don’t have to puzzle it out themselves.

“Cutter and Paste: A DIY Guide for Catalogers Who Don’t Know About Zines and Zine Librarians Who Don’t Know About Cataloging,” by Jenna Freedman and Rhonda Kauffman provides a more in-depth look into zine cataloging.

Consider adding a page to your school library’s website to promote zines, particularly if students are creating them. The page could include information about zines, tips to find them in the catalog, reviews, events within the school or community, and information on how someone might submit one for purchase consideration.

Bins or face-out display racks are great for browsing and circulating zines, but if you need to retrieve specific titles by catalog number, they won’t stay ordered. Other solutions include magazine boxes, clear hanging folders, and using retail-type displays creatively. Zinelibraries also provides some suggestions.

Cathy Camper is an artist, librarian, zine creator, and author of books for children and teens.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!