Talking with 'Kira-Kira' Medalist Cynthia Kadohata | The Newbery at 100

Kadohata reflects on winning the Newbery, writing longhand, and how her work has enriched her connection to her Japanese American parents and their experience.

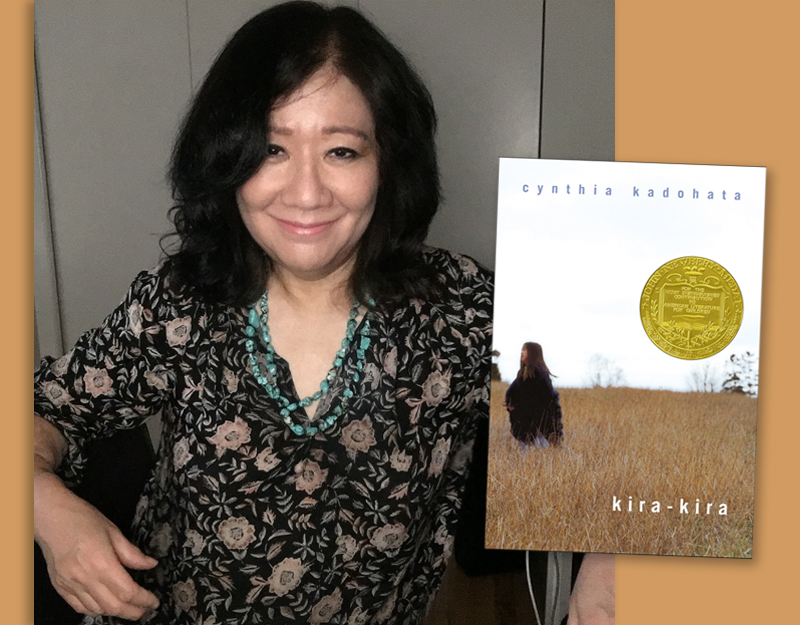

Cynthia Kadohata is the author of 10 books for young readers that encompass a remarkably wide variety of topics, settings, cultures, and time periods. Whether she’s exploring the aftermath of the Japanese American incarceration during World War II, contemporary wheat threshing in the Midwest, or the love of an animal companion, all her works are anchored by a sense of heartfelt authenticity as characters navigate complex emotions and situations. Her reflective storytelling deftly balances darkness with light and consistently affirms the importance of family and connection. She was awarded the 2005 Newbery Medal for Kira-Kira, and her latest novel for young readers, Saucy (both Atheneum), was published in 2020.

Since we’re celebrating the 100th anniversary of the Newbery Medal, let’s talk about your experience with this momentous award. It’s been more than a decade since you won it for Kira-Kira (Atheneum, 2004). Tell us a little about how winning the Newbery has impacted you over the years. What does its legacy mean to you?

Hmmm, mostly I just think of my writing teacher, the late Eve Shelnutt, asking the class if we were writing for today’s readers or tomorrow’s. She said that she was writing for tomorrow’s readers. This made us aspiring writers feel quite superficial for wanting to write for today’s readers. But the Newbery gives an author the best of both worlds—you have readers today, and will tomorrow, after you’re gone. I don’t know why this should mean a lot to me—after all, I won’t be here, but it does.

What memories stay with you about the process of writing Kira-Kira? Were you on a deadline? Did you outline the story, or write by feel? Your son was a toddler at the time. How did you balance early motherhood and writing?

I wrote the book in 2002. At my editor’s request, I tried to outline it twice for her, but each time she told me, “This isn’t really an outline.” To this day I have no idea exactly what she wanted when she said “outline.” So I did that little bit of outlining, and then I mostly wrote a lot by feel. At that time I was transitioning from writing the first version in longhand to writing almost entirely by computer. I think the part about [my character] Lynn seeing the little moth flitting about was in longhand. I actually took that from something I saw my dying dog, Sara, do in real time as I was writing. She looked at a little moth flitting around, and it seemed as if she knew that it was a type of living that she would never feel again.

I turned the manuscript in at the end of 2002. The only thing I can recall about Kira-Kira from 2003 was getting the book jacket. I absolutely loved it. I loved it so much that in my mind it was as if I had created it! (Russell Gordon, who actually designed the cover, will always have a special place in my heart.) Kira-Kira came out in February 2004. And then, feeling like nobody was even reading or noticing Kira-Kira, I flew to Kazakhstan at the end of April to adopt my son. I stayed in Kazakhstan for almost eight weeks. That was truly the adventure of a lifetime, and no words can do it justice.

And then, winning the Newbery in 2005, with the call waking up the entire house including my baby, was simply amazing. It was just unbelievable.

Over the last decade, there’s been a much-needed call for increased diversity in children’s books but you were writing about the Asian American experience for children several years before the demand for diverse books grew, not only with Kira-Kira in 2004, but also with Weedflower in 2006, and The Thing About Luck (all Atheneum), which won the National Book Award in 2013. What was it like being a trailblazer in raising the visibility of Asian American stories in children’s literature?

When I started writing, people said things to me like, “Nobody [in America] wants to read about Japanese people.” I worked at Sears during college and another saleswoman literally laughed out loud when I said I wanted to be a writer. Years later, when I sold my first book to Viking, people actually asked me whether Viking had bought it only because I’m Asian.

But I’ve been extremely fortunate. I came along at a fortuitous time, when the world was changing. I never felt like a trailblazer. All I knew was that I wanted to publish SO BADLY. I always tell people I was an animal during those early years. I refused to take no for an answer. I sent The New Yorker stories four straight years in a row for a while I was sending a story nearly every month until they finally accepted one in 1986. “No” meant absolutely nothing to me.

You’ve put quite a bit of your family’s own history into your books, especially Kira-Kira and Weedflower. When you were growing up, did your parents discuss being incarcerated in the Poston Internment Camp during World War ll, and the challenges of rebuilding their lives afterward? How has writing played a role in processing your family’s experiences?

Writing gave me an appreciation of my parents that I would not have had otherwise. Many nights I pray and ask for forgiveness for not understanding earlier everything that my late father went through, and how hard he worked to give my siblings and me the dreams and chances that he would never havecould never have. Now it’s time for us to take care of our mom, and I’m able to help with a different perspective of who she was and the era she grew up in.

Writing has enriched my view of who both my parents were and how hard it was for them. I think for Japanese Americans whose parents came out of that era, our parents lived truly heroic lives. They left internment camps with absolutely nothing and built lives for their children out of what amounted to sticks and rocks and sweat and incredible humility. [They…] believed their children should have dreams.

The Japanese phrase “kira kira” is translated in English as “sparkling” or “glittering,” but that definition doesn’t seem to adequately express the real character of this phrase it’s often used as onomatopoeia for the “sound” of sparkling and doesn’t have an exact equivalent in English. Are there any other uniquely Japanese words or phrases you love?

Every time I write a book with Japanese characters, I have long exchanges with a friend who is native Japanese where we discuss the nuances of words and phrases. She always nudges me out of one way of seeing the world and into another. I don’t know how she feels, but it seems what we discuss most is what I think of as the Japanese way of believing that the world is simultaneously transitory and forever; broken and beautiful. Kintsugi, or kintsukuroi, where someone fills cracks in broken ceramics with gold, is just so beautiful—to look at and as a concept. Someone I know recently made a cape from old kimono fabric for a relative who was badly injured in a car accident. She made gold “cracks” in the fabric, as a symbol of what the injured relative has now become: a little beaten by life, but still magnificent nonetheless.

You wrote several short stories and novels for adults before diving into the children’s literature sphere. What drew you to write for younger readers, and what do you find most rewarding about writing for a young audience?

A friend of mine suggested we watch a Zoom reading by a writer we went to grad school with. As I watched the introducer and the writer a bit, I was struck by how world weary they were, by how they had been there and done that. I love children’s books because one’s readers have NOT been there and done that. They are excited by life. Writing for this audience has really made the world more of a continual surprise for me. I have taken on that sense that I very much have not been there and done that. Everything is new.

Tell us a little about your writing process. When you get an idea, what’s your first move? How do you know when that idea is ready to become a full-fledged book? How has your writing process changed over time?

I used to write notes everywhere. I would lie in bed and have a thought, and then I’d have to turn the light on and write it down so I wouldn’t forget it. Eventually, I had slips of paper all over that no longer made any sense to me. What does “white paper bag” or “broken window” even mean six months after you wrote it down? Now I’m writing at the computer and I’m not worried about getting every thought down at every moment of the day. It’s actually more relaxing this way! I try to bring the focus to the time and place when and where I need to be focused, and I’m living life during the time and place when and where I need to be living life. This is better for a mom.

I would also say that [over time], the process seems more liquid. Instead of an almost list-making, 1-2-3 process, it’s more of “a flow with the universe” (lol, I’m showing my '60s roots here)! I actually enjoy the process much more than when I was a younger writer when I was an “animal.” There is something joyous about being young and a little bit of an animal, but it’s not really a state you can maintain for decades.

Allison Tran is the head of youth services at the Mission Viejo (CA) Library. She has reviewed books and apps for School Library Journal for over a decade.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!