School Librarians Must Lead the Ongoing Conversation About Problematic Titles and Library Collections

The furor over Dr. Seuss Enterprises' decision to stop publishing certain books may be over, but the conversation about evaluating titles for children's collections is ongoing. School librarians must lead the way.

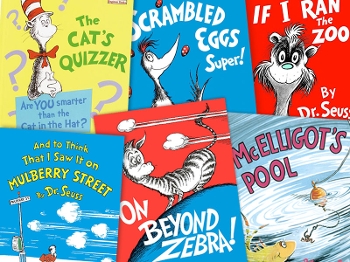

When Dr. Seuss Enterprises announced that it would stop publishing six Seuss titles because they portrayed people in ways that were “hurtful and wrong,” cries of “cancel culture” flooded airwaves, news columns, and social media. School librarians were not above the fray. Facebook groups and Twitter threads raged with arguments and vitriol more fit for political talk radio than a professional network of educators.

“I think sometimes some people are woefully or deliberately ignorant to a fact, and they’re so prone to ‘we’ve got to argue’ that we can’t have consensus with something that’s very obvious,” says American Association of School Librarians (AASL) president Kathy Carroll, library media specialist at Westwood High School in Columbia, SC. “We’re having all of these arguments about it. I think we’re ‘arguing’ about the wrong thing.”

The discussion shouldn’t be about what happened, but why it happened, says Carroll. It’s the why that matters and informs future decisions. And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street is not the first chapter in this story, and it certainly won’t be the last.

“You can’t put this genie back in the box,” says Carroll.

Some librarians may feel overwhelmed or conflicted making certain decisions, but it is basic collection development, says Erika Long, librarian at Thurgood Marshall Middle School in Nashville, TN.

“Some people might think this is tricky, but it’s not tricky at all,” says Long. “It boils down to every single thing that we were taught in school. We’re taught there’s pedagogy behind this. The same way that we would look at a piece of literature from a developmental standpoint and determine whether it belongs in the collection, we also need to do so—especially in this time—from a character standpoint. How does this help or harm the institution that I work in and the community that we are part of? Is this still relevant? Is this appropriate to where we are as a society and where we still need to go?”

It is reading, re-evaluating, and weeding when deemed necessary. Libraries are not archives, says Ryan Tahmaseb, director of library services and an English teacher at the Meadowbrook School, an independent pre-K–8 school in Weston, MA. In Tahmaseb’s library, he is the decision maker on the library’s collection and the discontinued titles came off the shelves immediately. No title is untouchable, he says.

“Whenever a book diminishes human beings through harmful stereotypes or racist language or imagery, that book has no business being on a school library bookshelf,” says Tahmaseb. “There’s no shortage of high-quality books that we can replace them with.”

“Whenever a book diminishes human beings through harmful stereotypes or racist language or imagery, that book has no business being on a school library bookshelf,” says Tahmaseb. “There’s no shortage of high-quality books that we can replace them with.”

But many, especially in public schools, will say it’s not so easy. Administrators, parents, and school boards weigh in on decisions. Others don’t know where to start when upending the status quo and taking perceived classics or sentimental favorites out of collections.

“We begin this process by thinking carefully about what students need,” says Tahmaseb. “No matter where we teach, our students need diverse books because of the opportunities they present to see themselves and others in new ways.”

Communicating with a diverse professional network can help librarians through these decisions, Tahmaseb says. Carroll agrees, even if it won't always be easy.

“We have to have the courage to look at some of our classics,” she says. “Even if it makes us uncomfortable, we have to investigate.”

Librarians must be “honest enough to look at all of the shadowy corners once held untouchable and acknowledge them for what they are,” says Carroll.

For Black school librarians, including Long and Carroll, the conversations can be more difficult.

“There are moments you have to check yourself because you can feel that passion rising,” says Long. “You have to take this deep breath and remember that, number one, I’m in a professional setting, and number two, nobody hears my point when I’m arguing with them.”

“Even if somebody gets heated and the conversation turns into a debate,” she says, “I still have to be the person that keeps my emotions in check, because in so many different instances, it is expected that I have an attitude or I become angry. And then buying into that stereotype then says to them, ‘This is why we can’t have these conversations and they’re just angry because they’re angry.’”

Difficult or not, Long won’t stop having these conversations.

“This goes back to AASL and our mission and our standards—we are supposed to be transforming, teaching, and learning,” says Long, who is also the AASL secretary. “That doesn’t just mean with our kids, our learners; that means with our other educators. How are we sharing this knowledge among ourselves as school librarians? How are we also teaching or educating our peers in our buildings and across our states?

“The work has to start with us.”

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!