Review of the Day: The Journey of Little Charlie by Christopher Paul Curtis

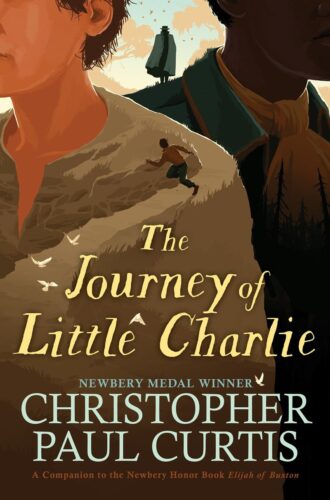

The Journey of Little Charlie

The Journey of Little Charlie

By Christopher Paul Curtis

Scholastic Press

$16.99

ISBN: 978-0-545-15666-0

For ages 9 and up

On shelves now

I don’t know Christopher Paul Curtis personally, but if I had to harbor a guess I’d say he’s the type of author that doesn’t like to make things too easy for himself. That’s one of my theories. Another is that he’s a writer that, as a rule, listens to his creations. Folks say that when you write, your characters have a tendency to take on a life of their own. You might try to get them to go one way and they’ll just peel off and go another without so much as a bye-your-leave. A character, a good character, has a strong personality that will not be denied. And in the case of The Journey of Little Charlie by Christopher Paul Curtis, a hijacking was clearly involved. As Mr. Curtis says in his Author’s Note, he was going to alternate the text of this book between two boys. Little Charlie (white) and Sylvanus Demarest (black). Only problem is, he started writing for Little Charlie first and, as he says, “the story had other plans.” So it is that Mr. Curtis has written his first middle grade novel starring a white kid with a mouth full of Southern dialect. None of this book feels like it could have been easy to write. But reading it? Easiest thing in the world, and downright pleasant to boot.

Things look bad for our hero. Little Charlie is kind of having an unfortunate run at the moment. First his dad just up and dies on him while chopping down a tree. Then he’s almost arrested for killing his dad (the old “a tree did it” excuse isn’t panning out for him). And now, worst of all, a horrifying overseer from a rich neighbor is claiming Little Charlie’s dad owed him money and, as repayment, he’s taking Little Charlie to the North on a job. According to “the cap’n”, as the man is called, they’re just going to collect on a longstanding debt. Problems arise, however, when it becomes clear that the “debt” consists of runaway slaves. Suddenly Little Charlie doesn’t want anything to do with this business, but the cap’n has other plans. Particularly when he discovers that the slaves he’s catching have a son up in Canada by the name of Sylvanus. The cap’n is convinced he can get the full family back to the South. What he doesn’t realize is that when Little Charlie is set on doing the right thing, not a man in the world should stand in his way.

So let’s sit down and examine the very first sentence in this book. Not the James Baldwin quote, though that is noteworthy. Not the place setting that puts it, “Just outside of Possum Moan, South Carolina – August 1858”, though that doesn’t hurt, and I suspect Mr. Curtis should be given extra points for coming up with “Possum Moan” as a place name anyway. The real first sentence reads, “I’d seent plenty of animals by the time I was old ‘nough to start talking, but only one kind worked me up so much that it pult the first real word I said out of my mouth.” Okay then. Curtis isn’t going halfsies to ease you into this. That’s dialect, pure and simple. Southern dialect, and written on the page. Pulling from the Mark Twain School of spelling and grammar, the first official written page of this book doesn’t make it easy for the reader so you’d better grab on from the get-go and get on board with his style, or let go and find yourself another book because he is NOT going to slow down for you. The upside of dialect is that it’s a shortcut into a specific place and culture. The downside is that some readers will give up on it instantly. I’m including adults in that assessment. This is a true pity since Mr. Curtis, ever the wordsmith, knows how to get a good line out of Little Charlie’s particular way of seeing the world. For example, consider the following sentences:

“But I seent it, and unseeing something’s the same as unringing a bell; it ain’t never been done. I don’t care how much you want to get rid of the remembering, you might as well not fight it, you might as well jus’ go ‘head and make yourself a holster, ‘cause that memory is yourn and you gonna be toting it ‘round for the rest of your life.”

“If the chance come up, go sneak a look at the backs of Alda Daponte’s hands and arms. She wasn’t but four when it happened and there’s still dirt that got blowed into her so hard that it went under her skin and ain’t coming out till the worms chaw through and reclaim it.”

“You can learn from anybody. Even dimwits can teach you if you listen careful and pick out the kernels of corn from the horse crap they’s dishing out.”

“… even a twenty-year-old, half-dead porch mutt with a snout full of snot wouldn’t have no problems pointing out which direction the cap’n come from and which way he was heading, not even in a hurricane.”

Honestly, it does remind me of Pogo from time to time, but that’s hardly a problem for me. And to be completely honest here, I was hooked on the voice by page three. Colloquialisms. They slay me.

Of course, Christopher Paul Curtis is perhaps best known for his characters. He brings them to life in all sorts of subtle ways. Gets deep into their heads and then, through their eyes, is somehow capable of rendering the people around his protagonists three-dimensional as well. Darned if I know how he does it. Little Charlie himself is a good example of this, particularly since he’s a flawed character. There’s been a lot of talk recently about whether or not kids are capable of understanding a historical character who grows and changes through the course of a book, particularly if part of their journey involves how they see race. Honestly, the book this reminded me the most of was The Hired Girl by Laura Amy Schlitz. In both cases you have a rural, ignorant white character that grows and changes slowly. Charlie’s journey, however, is a bit faster than you might expect. He uses the term “darky” and he is allowed some resentment when he realizes that Sylvanus and his friends dress better than he does. Otherwise, he’s a pretty forward thinking individual. Now we can go back and forth and debate the degree to which this feels real, but for my part I felt that Mr. Curtis kept Charlie within the confines of his times pretty securely. Compared to his countrymen he makes huge mental strides, but in terms of today he would still have quite a far ways to go. Makes for a good talk with kids when they read this book, that’s for sure.

You know how I can judge whether or not a villain in a book is any good? It’s easy. If, at a certain point in the book, I can read no further without knowing for certain if the baddie will get their just desserts I will (oh horror of horrors) be compelled to skip to the end of the story. And in the cap’n Mr. Curtis has created a magnum opus of scum and villainy. I haven’t felt this wrapped up in a soul this shriveled since I read Lauren Wolk’s Wolf Hollow a couple years ago. The cap’n belongs to a longstanding tradition of giggling sociopaths. You know the kind I mean. You see them crop up on television shows and in movies all the time. Their power derives not so much from their evil acts (which, in the case of this book, are far more horrifying than you usually see in middle grade fiction) but the sheer pleasure they take in causing pain. The cap’n is the strongest bad guy Curtis has ever conjured up. He’s like an escapee from Django Unchained. A bonified sadist lurking in the pages of a children’s book, and it all comes down to his perverse sense of humor. If you fear for Little Charlie and Sylvanus, and you do, you have very good reason for it.

I read a review of this book that said that in terms of heart, characters, thematic elements, and sheer literary quality, Mr. Curtis is the one to beat, but that the area where he falls short more often than not is in his plotting. In his Author’s Note Mr. Curtis does mention that when he writes, “Even though there is no outline, most times when I start a novel I do have an idea where I want the story to go, but (and I’ve learned this through time and pain and struggle) if the story is a good one, it has a mind of its own and eventually it goes where it wants to go.” The critic said that in the case of this book the ending could have had more punch and pizzazz. I’ve been chewing this over in my mind for a while, Certainly I recognize that I don’t generally pick up a Curtis book with plot in mind. He’s not a plot-forward kind of guy. Compare this book, for example, to The Mad Wolf’s Daughter by Diane Magras, coming out around the same time. That book runs helter skelter on the plot, working characters and motivations in as it scurries towards the finish. Curtis, by and large, is a slice of life kind of guy. He doesn’t immerse you in the time period as much as he immerses you in the brains of his heroes. There’s a reason he remains glued to first person narratives. But even as I say this, I’d also argue that while some of his books do meander a bit, I felt that this one had a definite end goal in mind. Yes, Charlie and Sylvanus are saved in a kind of deus ex machina fashion. No question. But not since Elijah of Buxton was I gripping my seat for quite this long a period of time. And that’s got a lot to do with the plot too, you know. A lot.

I’ll confess to you that due to the state of the world today, I’ve a weird inclination to take any children’s novel I see and to examine it closely, just in case it’s saying something about . . . well . . . the state of the world today. Since this is a book starring a poor, ignorant white boy I wondered if there was some underlying theme about privilege. In the end, though, I think Mr. Curtis is going for something bigger. One passage from his Author’s Note that really stuck with me (particularly in the past few weeks) is when he wrote, “We’re all heroes in our dreams. When looking back at some grand historical injustice I’m sure you’ve probably done as I have and said, ‘If I had been around at that time I would’ve…’ Then you fill in the blank with whatever courageous, life-endangering action you would have taken to right this wrong. Which is fine, except chances are good that that’s pretty much a self-delusional lie.” But all is not lost. In Little Charlie, Mr. Curtis wanted to show that once in a while you find someone in this life that carries with them that “great courage to which we all could aspire.” As an author, he puts that courage down on the page. He then puts us in the head of our hero so that we can see his doubts and feel his fear, just as we would fear. Then he does the right thing and, through him, we have done the right thing too. For just a moment, we are heroes in another man’s story. That’s why we dream of what we might do if we faced the impossible. And maybe, with the help of stories like this one, readers will have just that much more courage when their call comes. A great grand book that stands taller than its slight packaging would lead you to believe.

On shelves now.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

- The Hired Girl by Laura Amy Schlitz

- Wolf Hollow by Lauren Wolk

- The Mostly True Adventures of Homer P. Figg by Rodman Philbrick

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!