‘Banned Book Club’ Authors Speak Out After Their Work Is Temporarily Banned in Florida

The challenger claimed that the graphic novel "damaged souls." The authors have several things to say in response.

The graphic novel Banned Book Club was recently banned. And while the book was returned to the shelves of the Clay County, FL, school district within a few days, its authors have a lot to say about why it was banned and how the challenger’s strategies mirror elements in the story.

The graphic novel Banned Book Club was recently banned. And while the book was returned to the shelves of the Clay County, FL, school district within a few days, its authors have a lot to say about why it was banned and how the challenger’s strategies mirror elements in the story.

In April 2023, Banned Book Club, which was nominated for an Eisner Award and received a starred review from SLJ , was challenged and temporarily removed from Clay County School libraries. It was restored after a new challenge oversight committee deemed the challenge to Banned Book Club, and more than 100 other titles, to be frivolous.

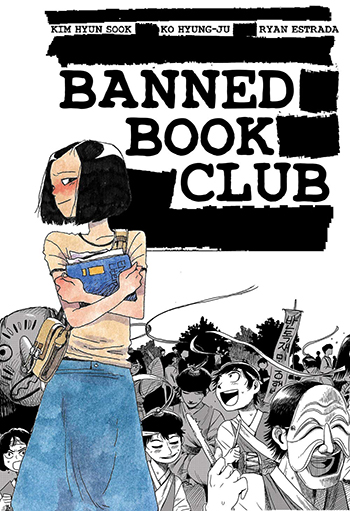

Created by the husband-and-wife writing team of Kim Hyun Sook and Ryan Estrada and artist Ko Hyung-Ju, Banned Book Club (Iron Circus, 2020) is based on Kim’s experiences as a college student in Korea in the 1990s, when she and her friends would meet in secret to read and discuss books that were being suppressed by the authoritarian government of the time. The graphic novel depicts the students being harassed and beaten by police who suspected them of possessing books that fell afoul of the regime.

The creators see parallels between the book’s events and the political climate that led to its challenge. While this challenge was quickly reversed, that may not be the end of the story, they say.

“Being put back on shelves also puts a big target on our back,” says Estrada. “The organization has a big database of titles, and ones that are not permanently banned are marked in bright red, considered a failure, and then made a priority for appeals.”

Indeed, Banned Book Club has already appeared on another list compiled by a group in Michigan.

The Clay County challenge was among the 100-plus filed in that district alone by Bruce Friedman, president of the Florida chapter of the national organization No Left Turn in Education.

Many of Friedman’s challenges use identical language on the forms, including “Protect children!” as the reason for challenging a book and “Damaged souls” as the result of a student reading it. The specific objections to Banned Book Club include “anti-police sentiment,” “Molotov cocktails,” “creating dangerous anarchists in our schools,” resulting in “damaged souls,” and conclude with, “Does this book create better citizens? Nope.”

“I was kind of impressed that our book was deemed to ‘damage souls,’ until I realized that's just his catchphrase that he uses on every challenge,” says Estrada. “The much more personal concern was that our book was dangerously ‘anti-government.’ Clearly he does not understand the history the book teaches. It’s pretty ironic that a guy whose whole personality is fighting against the current government of the place [where] he lives thinks a history book about teens opposing the murderous military regime who dismantled their government in a bloody coup is too anti-government.”

Kim drew a parallel between the deliberate ambiguity of the Korean censorship regime and Florida’s approach.

“Korea never had an official list of banned books,” she says. “They could just decide whatever book you had on you was banned and prosecute you for it. This led to people self-censoring.

“In Florida, the new laws are so purposely vague and contradictory that no one knows what to do. Various threats are being thrown out, like saying teachers who distribute ‘inappropriate books’ could be charged with a felony. But since they never defined ‘inappropriate,’ many schools just removed every book from their building out of caution.”

That’s what was happening in Clay County before the new screening committee was established. The list of books challenged in that district indicate that many were “deselected/weeded.”

“Librarians were pressured to self-remove books that No Left Turn in Education and the district wanted to ban, by threat of prosecution,” says Estrada. “They refused to do that anymore, leading to this committee making all the decisions for them.”

Estrada points to another similarity between book banning in South Korea in the 1990s and in Florida in 2023: Politics. The Korean regime of the 1990s banned books about communism, because readers might realize that Korea had many of the same problems as communist countries. Similarly, because the regime claimed to be democratic, it banned books about democracy, Estrada says.

“They knew if people read the real definition of democracy, people would realize they didn't have it,” Estrada notes. “Likewise, Florida is banning books that even vaguely mention social injustice, because it’s not something they want people to strive for. And of course, they banned a book about the danger and motivations behind book banning under a dictatorship, because they don't want to be judged for following the exact same playbook.”

“Our book is not about politics,” Kim adds. “It is about a group of nerdy friends hanging out and trying to live their lives. They want to do well in school, make friends, and meet cute boys. But because of the climate I grew up in, political situations interrupted all of those things. It's all history, but maybe that history hit a little too close to home. There's a line in our book that says, ‘Do they ban books because they see danger in their authors, or because they see themselves in their villains?’”

Estrada regularly makes presentations to libraries and has kept up to date on the recent wave of book challenges. But even he was surprised at what happened during a recent video workshop.

“I was giving my usual talk, and the school librarian did something I'd never thought to do,” he says. “She asked ‘How many of you even knew this was happening?’ Zero hands came up. Then she went on to describe all of the abuse, harassment, and career-threatening situations she faced on a daily basis to keep their library as uncensored as she could. It blew my mind that none of her students knew about it.”

Since then, Estrada has been making even stronger efforts to educate people about the challenges.

Kim, who has already lived through this once, understands the endgame:

“There's a scene in our book about the moment I realized I'd grown up in a military dictatorship,” she says. “I asked my friend why our parents had hidden that fact. He said, ‘They just got so beaten down by all of it for so long that they got tired of talking about it. It became normal.’

“That's their plan,” Kim continues. “Ban so many books that everyone tires of thinking about it and ignores when they start firing teachers for having textbooks with the statue of David in them, shutting down whole libraries, or trying to pass laws where a bookstore can be prosecuted for carrying certain YA books. So, we have to keep talking.”

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!