"Progress is never in a straight line." | Martin W. Sandler, 2019 National Book Award Winner, Talks History

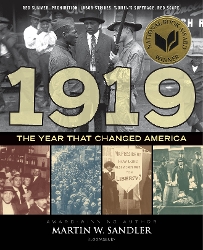

SLJ spoke to Martin W. Sandler, author of 1919: The Year That Changed America, about his 2019 National Book Award for Young People's Literature, his creative inspiration, and his extensive research process.

1919 was an explosive year in American history: molasses flooded the town of Boston; women fought for the right to vote; lynchings of African Americans led to the birth of the civil rights movement; the World Series experienced a shocking scandal. Martin W. Sandler is known for his excellent work in documenting the history of America. This November, the award-winning author earned the 2019 National Book Award for Young People's Literature for 1919: The Year That Changed America (Gr 7 Up, Bloomsbury).

SLJ spoke to him about his newly bestowed honor, his creative inspiration, and his research process.

Congratulations again on the National Book Award for Young People’s Literature.

Oh my god, I still can’t believe it but it’s wonderful. I was just absolutely thrilled. When they called my name, I couldn’t believe it.

In addition to 1919, your previous books focus on specific moments or people in history. What time period in American history has been your favorite to research over the years? Why?

I really don’t want to be silly or be vague but, honest to goodness, I’ve researched almost every period and the Civil War period is absolutely fascinating. I think the movement westward and some of the stuff I’ve done on that [is my favorite]. These are, of course, real pioneers and these are very brave people. And these are people risking it all to build a new life. But of course, you can say the same thing about immigration and the people who came from Europe in the late 1800s and 1900s and were willing to risk everything to build a new life, particularly for their children. Those are real heroes; they truly are.

How do you go about gathering research?

It truly is all about the research. And fortunately for me, that’s what I like to do best. After writing more than 60 books, if I do my research right, if I can’t write it right, then I’d have to throw my pen away. I do all my own research for several reasons.

Very often when I’m researching a topic I see something else and that says, “Hey I gotta go back and look at that. That might be my next book,” and it’s happened several times. And sometimes when I’m doing research, I find something and it changes the whole darn direction of the book I’m going in.

And no matter how good a researcher I can hire, they’re not going to do that for me, they can’t do that. It’s my book. And frankly, I’m a control freak and I want to control the research as much as I can. To me, if it’s done right and it’s the right topic, then it’s like a detective hunt. And what I try to do, always, is to let the people in the story tell the story. I think that's what gives it life, that’s what makes history come alive, and that’s what makes it as engaging as it is informative.

When discussing Prohibition, you make an interesting statement: it was a look at what happens when the government attempts to legislate morality. How has Prohibition influenced and/or shaped our current government?

When discussing Prohibition, you make an interesting statement: it was a look at what happens when the government attempts to legislate morality. How has Prohibition influenced and/or shaped our current government?

I think that’s one of the most important things in the whole book, frankly. What I tried to do throughout the whole book is at the end of each story, is bring it up to date. It was amazing to me when I really for the first time looked into 1919 and saw how many terribly important things happened in that one year.

Because of the molasses flood, the first business codes were put in, the first time it was against the law to build anything without professional architects and blueprints and building codes. The biggest thing in the whole book is that it’s almost impossible to believe that the government could make up a law that says ‘you cannot buy a drink,’ ‘you cannot sell a drink,’ ‘you cannot manufacture a drink’…So this whole conflict between personal liberties and public good is something that goes on and on and will go on forever.

As a sports fan, and because I know you researched it well, was the Black Sox Scandal one of the first reported instances of sports gambling?

It’s one of the first reported and to this day, we haven’t had a bigger scandal. There’s no bigger scandal than throwing the World Series. And it’s another case of everything in this year being related. One of the things that came out of Prohibition was the birth of the American gangster. The same gangsters who financed and made billions out of Prohibition were the ones who financed the Black Sox Scandal. It was extraordinary. I can’t imagine it could happen today with the scrutiny it gets.

One of the saddest chapters to read was the section on Red Summer: the lynchings that occurred and the violence against African Americans. Out of all the issues mentioned, do you think it’s an area that we, as a society and government, have made the least progress?

What bothers me most, without getting political...is the way that government has become so politicized. You know, if you're a Republican you have to believe this way, and if you're a Democrat you have to believe that way. I’m old enough to know that there were times that no matter how they disagreed they did try to work together. There’s no such thing as compromise anymore. So I think that’s one of our biggest failings. But of course, what you just brought up is another one.

We’ve come a long way in civil rights but we have such a long way [to go]. The same is true with women’s rights. We’ve come a tremendous way but we have an awful long way still to go. I think we will but it’s too bad to think of how much time it takes. One of the best lines, I really believe in and I’d like kids to know is that there’s progress—we are a nation of progress but progress is never in a straight line. And sometimes we fall back but somehow we manage to push ahead again, and you have to keep that in mind.

Speaking of progress, take, for example, our country's history concerning immigration. According to sources, during the decade leading up to World War I, an average of 1 million immigrants per year arrived in the United States. Nativism started to gain popularity following the end of the war.

We’re a nation of immigrants. For anyone to try to be blocking [immigration], you’re blocking our heritage, you’re blocking who we are, and you’re blocking our strengths. That’s the ironic thing. Somehow we will get through it all because we always have, and I have great confidence that we always will. But, man, when you’re living through it, it’s not easy.

I’ve read that as you research you come up with new ideas for your next book. What has piqued your interest lately?

Believe it or not, I’m doing two books right now. I’m doing a book about the birth of flight and I’m doing it in a way to break down a lot of myths about how flight really came about. It really centers on the first air meet that took place in one week in Rennes, France, in which the airplane went from something regarded as a toy to something regarded as the future.

And then, early on in my career, I wrote several books on the history of photography. Not about taking pictures but the history of photography because I was fascinated by it. I always have been. I have always known that the greatest photographic collection in the world, to this day, by far, is the collection that was taken during the Great Depression by a government agency, the FSA, that set out to take pictures of farm agents helping poor farmers. Instead, they threw all those pictures away and they did a photographic record of the United States. That’s the first time that’s ever been done before or since.

And finally, I have been asked to do a book on baseball. I think I’m going to do a book on 1941, the greatest year in baseball history. In 1941, my hero, Ted Williams hit .406. No one’s ever going to hit .406 again. In 1941, Joe DiMaggio did a greater thing. He hit in 56 straight games.

Anything else that you’d like to add?

I’m so grateful to these judges for understanding that history can not only be important to young people but history can be as relevant to young people as anything being written in fiction. I’m very grateful to them for that, for having seen that and having given this [award] to a nonfiction history book. It was awesome and I still don’t believe it!

|

| Photo by Bloomsbury |

Martin W. Sandler is the award-winning author of Imprisoned, Lincoln Through the Lens, The Dust Bowl Through the Lens, and Kennedy Through the Lens. He has won five Emmy Awards for his writing for television and is the author of more than sixty books, four of which were YALSA-Nonfiction Award finalists. Sandler has taught American history and American studies at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and at Smith College and lives in Massachusetts.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!