Three YA Authors on Yearnings, Obsessions, and Hopes

Three YA authors tell SLJ about their favorite childhood books and take a deep dive into the main characters in their debut novels.

A trio of YA debut authors shares here some of their favorite books from when they were young. Safia Elhillo, Allison Saft, and Steven Salvatore also tell SLJ about the main characters in their books—their yearnings, obsessions, and hopes.

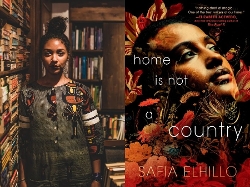

Safia Elhillo, Home Is Not a Country (March 2)

What were some of your favorite books as a child, and why?

I still have my battered copy of Neil Philip and Sheila Moxley’s The Arabian Nights—I don’t remember how old I was when I got it, but I was definitely in the single digits. I do remember being mesmerized by the illustrations, which are deliciously colorful and have gold detailing. The stories in it are old classics, like the story of Scheherazade and the king. Scheherazade’s trickery was probably the first time it was clear to me that stories are powerful and that the ability to tell a story matters. Plus, I loved the fact that nearly every story has jinn in it. The Arabian Nights reminded me of the stories I grew up hearing in my family and community about jinn and the spirit world—I could see my world reflected back in its pages.

You have written and published two collections of poetry. How did it feel to write a YA novel? Why did you decide to write Home Is Not a Country in verse?

It means a lot to me that my first novel is for young people. It started out as an offering to my younger self—being a young reader is the reason I am a writer today. I wanted to write a book that would have made it all feel possible for me sooner. It took me a while to really believe that the world I came from was deserving of poetry, of literature, because I wasn’t seeing my particular intersections in any books. I got by, seeing fractions of myself here and there, but I never saw the whole thing. So I wanted to tell a story about a young person who is not me, but who inhabits my intersections, and I wanted to offer this story to someone who is the age I was then, to add to the conversation they might be having with themselves about what is possible in a book.

Readers of YA are transitioning from one world to another, from childhood to adolescence, are in that in-between space that still feels so familiar to me in so many ways—I’ve spent my whole life between worlds, countries, cultures, languages. The novel-in-verse form, a hybrid form, felt like a perfect sort of mimesis to hold this in-between feeling, too. But the choice to write the story in verse ultimately came down to my relationship to verse and prose. I feel like I am never going to be fully fluent in English, or in any language, and verse has always been a space where I feel like the rules of language are mine to set, mine to play and experiment with and stretch. I feel less at the mercy of external measures of fluency in English, and instead feel the language soften and grow more malleable, able to mutate in order to accommodate the things I need to say. In a poem, I don’t feel bound by the rules of “proper” English or “correct” grammar. I get to invent my English as one of infinite Englishes, and set my own grammar. And I wanted to be able to tell this story with that set of tools available to me. Especially since the medium is new, I wanted to stay in the form where I feel most at home.

How would you describe the book’s main character?

Nima is a 14-year-old hyphenated American (from a country that is not named in the book but is based on Sudan) growing up in an American suburb, obsessed with the old songs and films and photos from the Arabic-speaking world of her origins, though she’s never been back. And so much of that obsession comes from her loneliness, her belief that if she’d only grown up there instead of here, she would be better understood, better contextualized, better company.

What do you hope readers will take away from Home Is Not a Country?

The title really is my thesis statement here, for this book and also for my actual life—a country is not the only way to belong, to identify oneself. It is maybe the least interesting way to do those things. Home is about love and community and care, not about borders (which are made up!) or about countries (which are also made up!).

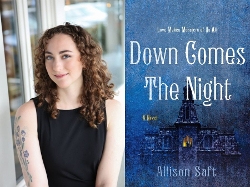

Allison Saft, Down Comes the Night (March 2)

Allison Saft, Down Comes the Night (March 2)

What were some of your favorite books as a child and why?

As a child, I was completely obsessed with Erin Hunter’s "Warriors" series! Those books hold a powerful transportive magic, and I adored the rich and immersive setting, the complex politics, and, of course, the many forbidden romance plotlines. I’m also a product of the golden age of YA paranormal romance, so some other favorites from my youth are Becca Fitzpatrick’s Hush, Hush and P.C. Cast’s House of Night series.

Why did you choose to write a fantasy book for young people?

I write fantasy novels for young people because YA fantasy rekindled my love for reading and writing. In the fall of 2017, the nadir of my post-grad malaise, I picked up Margaret Rogerson’s An Enchantment of Ravens and Melissa Bashardoust’s Girls Made of Snow and Glass. They felt so vibrant and full of heart, and I remember thinking, “This is how I want people to feel when they read my writing. This is what I want to do.”

How would you describe the main character in Down Comes the Night?

Wren is a sensitive soul who has bought into the lie that feeling things deeply is a flaw that must be outgrown. She cares passionately for others, sometimes to her own detriment, and she yearns to love and be loved. She’s witty, driven, and impulsive, but above all else, she’s kind in a world determined to make her cold.

You have set this book in such a richly detailed world. How did you come up with the ideas for the setting and the plot?

Book ideas typically come to me in the form of an intriguing romance dynamic. I knew Down Comes the Night would be the story of a healer who must care for an enemy soldier, but to make it work, I needed to trap them together and give them a common goal. The more I thought about the concept, the more apparent it became that Gothic novels—with their isolated, haunted settings; their interest in cycles of violence; and their mystery plotlines—would provide the perfect template for the book.

[Read: Four Debut YA Authors on Getting Published in a Pandemic and Staying True to Yourself]

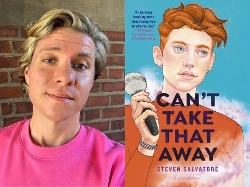

Steven Salvatore, Can’t Take That Away (March 9)

What were some of your favorite books as a child and why?

This is a really hard question to answer! Since there were no LGBTQ+ children’s books while I was growing up, my first thought was to take it by age range. The picture books that have stuck with me are Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are because of how it echoed the free reins of my own imagination and how I still channel that ability to disassociate from reality and dream up something entirely escapist in order to both cope and create, and Dr. Seuss’s Because A Little Bug Went Ka-Choo, which I still think about almost daily because of what it taught me about ripple effects and how small actions can have large consequences. As I grew older, I devoured R.L. Stine’s "Goosebumps" (what 90s kid didn’t?) and older mysteries like The Boxcar Children. But my favorite middle grade book from childhood is definitely From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler by E.L. Konigsburg; that’s the book I remember the most, that made me want to write and live my own stories. Besides, I always wanted to live inside a museum. I’ve always been a huge fan of museums. As a teen, it was definitely Laurie Halse Anderson’s Speak—I’m still in awe of her prose—and Stephen Chbosky’s The Perks of Being a Wallflower. Though I never experienced anything like what happened to the main characters in either book, the voices of both spoke to my soul.

How would you describe the main character in Can't Take That Away?

Carey Parker, the main character in Can’t Take That Away, is a beautiful optimist buried in layers of self-doubt. They want so badly to acknowledge that they are talented and fierce and powerful, but when we meet them at the start of the novel, they’re scared. They’ve already come out, but due to a series of events that happened prior to the start of the story, they’ve buried their confidence under fear to protect themselves. But they are talented and fierce and powerful. They just need to untangle all of the internal stuff that gets in their way. And I think the beautiful aspect of this story is that readers get to see that happen on the page as they navigate their relationships (friendships and romantic), go to therapy, and process some real-life trauma that many teens experiences, like the death of a very close relative, bullying, and heartache. I wanted to show Carey’s resiliency and strength, and how they find—and use—their voice.

Music is such a big part of this story. What is the role of music in your life?

I can’t do anything without music. Whether I’m washing the dishes, going for a run, or writing a book, music motivates me. I can’t start writing a new project without first creating a mood playlist, and the playlist has to echo the characters and feel of what I’m writing. If it’s not right, I can’t write. Beyond that, Mariah Carey has always been an incredible source of inspiration for me. Her talented songwriting abilities and godly voice have carried me through some really dark moments and shown me that there is power in my own voice.

How do you think LGBTQ+ representation has evolved in recent years in books for young people? What kind of work is there still to do?

It’s evolved tremendously over the last decade, but we still have a lot of work to do. When I was teen back in the late 1990s, early 2000s, there were no books that I could turn to for comfort, that told my story, so I never really thought that I had a story to tell or that I even belonged anywhere. I didn’t see myself anywhere, and I continued not to until I read Jeff Garvin’s Symptoms of Being Human as a 31-year-old adult, and then again with Mason Deaver’s I Wish You All the Best the following year. It’s not acceptable that there have been so few stories about non-binary main characters. As I grew into the person I am today, there were no books that might have helped me unpack my own identity the way writing Can’t Take That Away did for me. I hope it does that for at least one young person out there reading. In the 2000s, I noticed that most of the books were coming out stories, many of which were centered around trauma, and very few had much queer joy at all, and many of which were written by cisgender straight folks, and the ones that were #OwnVoices seemed to be buried (or only written by cis white gay men). For too long, it seemed like the only queer experience with adequate representation was the white cis gay male experience. That creates a great dearth of experience and skews perceptions of what queerness is and looks like because these stories were mostly told through a white cis lens and made palatable for straight audiences.

Within the last few years, I’ve seen more queer BIPOC writers emerge and their stories getting published, and these books are exactly where we need to be heading, but there still aren’t nearly enough; there have to be more. Publishing must do more to balance the scales. We need more LGBTQ+ BIPOC editors, literary agents, and publishers so that there can one day be true equity. And queer BIPOC readers deserve the opportunity to see themselves on the page. We also need librarians to request these books, and for teachers to assign this literature in the classroom to reshape the “literary canon.” I also think that, moving forward, queer books need to reflect the nuances of queer identity, and showcase all the complexities and joys and struggles of what it means to be queer today. We just need more, more, more, more books. And even then, it’ll never be enough because the LGBTQ+ experience isn’t a singular one—queer stories are infinite and always changing and sometimes undefinable, and that’s the beauty of being queer.

Melanie Kletter, a teacher and freelance writer in New York City, was previously a senior editor of TIME for Kids.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!