Three Literary Fiction and Poetry Authors Turn to YA

This fall, three acclaimed adult authors debut YA titles—including a National Book Award finalist. Jennifer Baker talks to them about writing across audiences, seeing teen readers as individuals, and trying to make the world better.

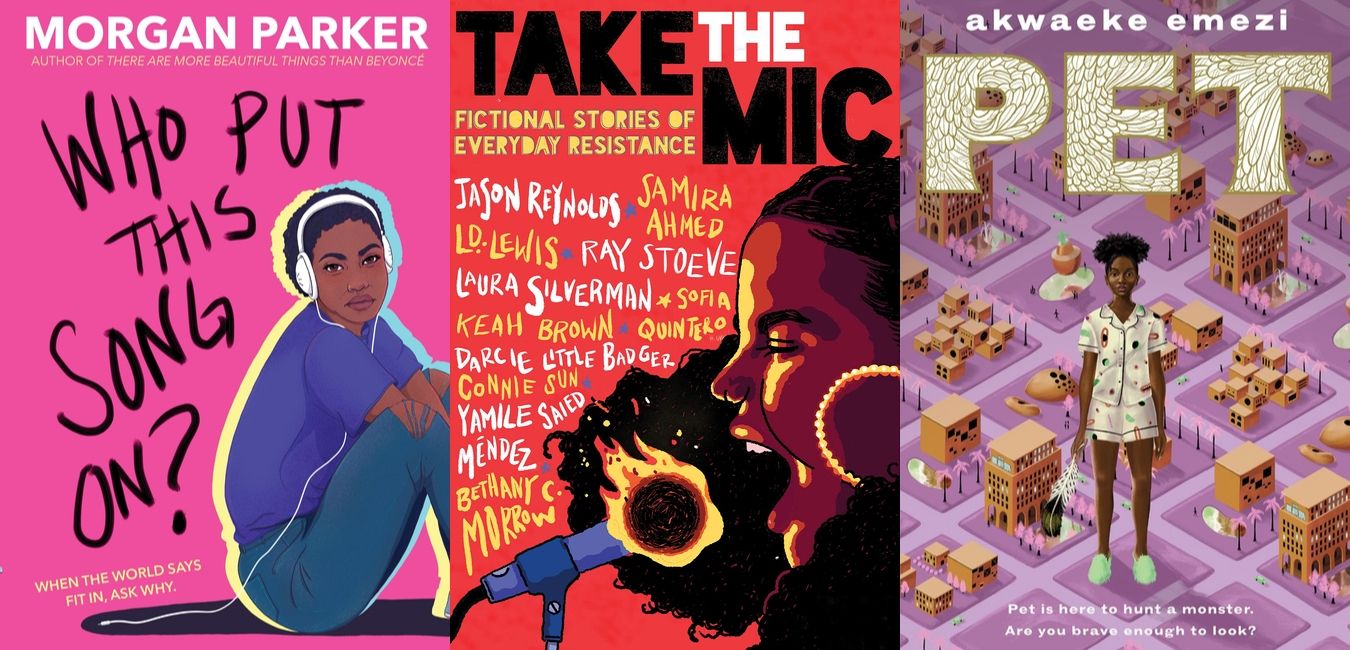

This fall, Akwaeke Emezi, Bethany C. Morrow, and Morgan Parker make their debuts as young adult writers having previously published adult literary/speculative fiction or poetry. History has shown that crossing over can lead to success in the YA world: Erika L. Sánchez and Elizabeth Acevedo both published acclaimed poetry titles prior to their much-applauded young adult novels, which were finalists for the National Book Award in Young People’s Literature. Last year Acevedo took home the award for The Poet X, and Emezi’s YA novel Pet was recently named a finalist for the 2019 award.

When I spoke to Emezi, Morrow, and Parker, they agreed the categorization as a particular type of artist can be limiting. They are writers, period, and from the vantage point of the creator, the scope of a project defines who stars it in and who it may be for. Emezi said they weren’t concerned about being pigeonholed as a specific type of writer when it came to their first adult novel. “By the time Freshwater came out I had written two other books [Pet and the adult novel The Death of Vivek Oji, publishing in 2020]. I knew Freshwater was likely to be the only book like itself that I had written or that anyone else had written.”

In Pet (Make Me a World), the protagonist Jam is a transgender Black girl on a mission to save her best friend Redemption with the help of the titular character, a “monster” in a utopian town that’s supposedly eliminated all the bad elements. But monsters aren’t always what or who they seem. This story came about as part of a challenge Emezi created for themselves, as well as a helpful directive from publisher Christopher Myers, who encouraged them to write the book they would’ve “needed as a teenager.” Emezi says their aim is to do something different with each book. “Pet is about making a better world. Which sounds really corny, but it’s the point of what every activist is trying to do. It’s the point of every revolution: people are trying to make things better.”

Bethany C. Morrow, editor of the young adult anthology Take the Mic

|

Bethany C. Morrow.

|

(Scholastic), said the prose and poetry encapsulated in the collection aims to provide marginalized teens visibility and validation in stories of “everyday resistance.” The contributions offer teens a platform to have their feelings recognized when faced with a lack of understanding or respect for their fear, rage, and discomfort by those with privilege. For example, Morrow’s story follows a Black teen who hopes she’ll be asked out by a white boy she has a crush on. What transpires—through no ill-will, though much ignorance—showcases the privilege of the white boy and the constant fear and endangerment Black girls face. “With the anthology, my goal was undoing gaslighting,” Morrow says. “It’s basically saying ‘You’re right. What you’re seeing is actually happening.’ And then hopefully giving permission to respond to the fact that they’re right.”

Morrow, whose speculative adult novella MEM was published last year, is purposeful in the work she offers younger readers. Not simply in terms of what she thinks they need, such as reaffirming their feelings in Take the Mic, but also how she presents the work and the young characters in it. “I’m concerned with not just not doing harm but, if possible, undoing harm.” She also has a magic-infused YA novel, A Song Below Water, coming out next June with Tor Teen.

|

Morgan Parker.

|

Morgan Parker has three poetry books out, most recently Magical Negro. Her young adult novel Who Put This Song On? (Delacorte) can be called autobiographical in some respects—it is based on her life and journals as a young adult—but it’s also a book that pushes against what she’s accustomed to seeing in art and literature: a fairytale narrative with a perpetual happy ending. “When I teach a college course of freshmen, I’m seeing the way that these narratives have really f---ed up their expectations of the world and that is not okay,” she says. “So that’s the first thing I’m thinking about. What we assume and what we understand at that age has a lot to do with who we become and what kind of expectations we have for the world.”

Who Put This Song On? follows teenager Morgan Parker—yes they share a name—one of the few Black people at a majority white Christian school, in a majority white city during the 2008 election when Barack Obama clinches the democratic nomination for president. In the book, Morgan has recently been diagnosed with depression and starts seeing a therapist. Like Emezi and Morrow, Parker says she’s able to create something that she can relate to that’s also for young people who need it. “I understand the need for that because of the teen who feels like an outsider, who doesn’t fit in.”

Emezi’s Freshwater is also considered autobiographical fiction, and it looks at the various selves within a human form. Parker’s poetry reflects a keen insight on Blackness and feminism. And Morrow’s novella MEM utilizes science fiction and history to illustrate societal issues of power, healthcare access, and longevity. Similar themes are also present within the work they are producing for teen readers. Parker understood and respected this when she was writing for a younger audience. “I found myself thinking a lot about that kind of idea of what our responsibility is to readers, especially young readers, and I take it really seriously,” she says. “I’m gentle with the Morgan Parker character, but I’m not all the time. And I’m pretty hard on myself, so that was maybe the hardest part to be gentle with that character. And also to be real.”

|

Akwaeke Emezi.

|

Emezi’s approach to creating a better world for Jam in Pet also meant looking at the themes they wanted to portray, and who they are writing for: they were adamant about writing “a Black trans story for Black trans kids.” This keyed-in perspective prioritizes the viewpoint of someone not often seen living a fully loved existence, or whose life has been dictated by cis audiences in a manufactured light. “Part of the function of Pet, whether for young people or for adults,” Emezi says, “is to get us thinking about what another world can look like in terms of justice.” Placing a Black transgender girl as the hero and making friendship, not romance or sex, a primary part of Pet’s storyline were also critical to the way this story played out differently from Emezi’s adult books. “All my other books have sexual themes to them or they’re adult in that way,” they say. “With Pet I wanted to see what it would be like if I just took that out of a book I was writing and allowed Jam to be herself.”

Moving from verse to narrative was difficult for Parker and ultimately resulted in trial and error. She took cues from what she’s learned over the years as a poet and applied this to her first fiction project. “There are maneuvers that are very poetic in terms of pacing, the structures of paragraph, things like that I knew with a poet’s eye,” she says. “And I feel really happy that that kind of poet eye and poet hand made its way into the book. Narrative itself was very confusing and stressful for me, I often forgot that I had to tie up certain things. That was the sort of thing, the logistics of it, that was what bothered me.”

When Morrow approaches writing for teens, she doesn’t look at them as a subcategory, she considers who they are as individuals. She’s a parent to a teen boy and mentions how much her upbringing—before social media and active shooter drills—doesn’t always mirror what her son goes through now. “I want to make sure I’m talking to kids who live my son’s experience,” she says. “He reminds me that they’re real people. They’re not some newfangled alien race.”

The high regard Emezi, Morrow, and Parker have for teens means their writing fully inhabits the joys and pitfalls of teenage life, whether it’s for a character who seeks out the true monsters in their world, teens pushing against forces that minimize their experience, or those learning how to express themselves, no matter how awkward things may seem. These writers respond to the challenges and big questions with great care to help younger readers see truer versions of themselves.

Jennifer Baker is a publishing professional, contributing editor to Electric Literature, and creator/host of the Minorities in Publishing podcast. Her work has appeared in various print and online publications. Her website is: jennifernbaker.com.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!