Librarians Support Students Amid Anti-LGBTQIA+ Legislation, Challenges

Advocates for queer young people say support from caring adults is crucial. Here's how librarians are standing up for their students.

|

Bradley Savella (left) with Cane Ridge High School librarian Tyler Sainato |

During his sophomore year in high school, Bradley Savella and his family moved from Hawaii to Tennessee.

“I didn’t even understand what culture shock was until I moved to Tennessee,” says Savella, who graduated in 2021.

It took him a while to find his footing at his new school. Savella was also grappling with issues concerning his identity. But he says things began to turn around for him once he made a few friends and was introduced to Tyler Sainato, the school librarian at Cane Ridge High School in Antioch, TN, a suburb of Nashville.

“She was just a breath of fresh air, and she would always make me feel so safe,” says Savella, who came out as gay during his high school years. “She also was an advocate for the LGBT community, and she directed me to the GSA [Gay-Straight Alliance]. Being in Tennessee is a little scary for LGBT students and children.”

Tennessee students are not alone. Across the nation, there have been an increasing number of laws proposed and passed regulating what students can and cannot be taught about gender and sexuality in schools.

Books with LGBTQIA+ characters or themes are also coming under attack from conservative lawmakers who argue that these materials don’t belong in schools. The concerted campaign includes restricting access to titles these groups feel are inappropriate for young people through challenges and book removal from school libraries.

The vast majority of these titles have LGBTQIA+ themes or deal with race. Half of the American Library Association’s top 10 list of most challenged books in 2021 concern queer identity, and the three most challenged titled—Gender Queer: A Memoir by Maia Kobabe, Lawn Boy by Jonathan Evison, and All Boys Aren’t Blue by George M. Johnson—all fall in this category.

Florida Governor Ron DeSantis called Kobabe’s memoir “a cartoon-style book with graphic images of children performing sex acts” after he signed a bill that gives parents a greater say in which books are allowed in school libraries. The climate and discussion are so fraught that several school librarians contacted for this article declined to speak with SLJ out of fear of negative and personal consequences.

Advocates for queer young people say support from caring adults like Sainato is crucial.

LGBTQIA+ teens and young adults are four times as likely as their peers to die by suicide, according to the Trevor Project, a nonprofit suicide prevention and crisis intervention organization for queer youth.

Of 35,000 LGBTQIA+ youth ages 13 to 24 surveyed by the Trevor Project in 2021, 42 percent had “seriously considered” attempting suicide in the last year. That number jumps to more than 50 percent for those who identify as transgender and/or nonbinary.

“I really do believe that this work can save lives,” says Sainato. “I feel like it is part of my purpose to amplify voices that are not heard often. My role in that is to provide a safe space where people can ask questions, where people can find refuge, where people can find books or other information where they can see themselves represented.”

Book challenges and political backlash

|

Sam Harris with students |

According to the 2021 Trevor Project survey, 94 percent of LGBTQ youth reported that recent politics negatively impacted their mental health.

An NBC analysis of data from the American Civil Liberties Union and Freedom for All Americans, an LGBTQIA+ advocacy group, found that nearly 670 anti-LGBTQIA+ bills had been filed since 2018, and that, as of March of this year, nearly 240 such bills have been considered.

In Tennessee, the state House passed a bill in March that would ban “obscene” books from school libraries. The state Senate plans to study the matter this summer before voting on it. Critics of these bills say truly obscene materials are already banned from school libraries, and this legislation will target books that feature LGBTQIA+ characters.

“The most frustrating part of that is getting adults who don’t read the literature to understand that it’s not obscene,” says Erika Long, a library consultant and former middle and high school librarian in Tennessee. “It’s part of the teen experience, or adolescent experience, to experience a kiss. But that doesn’t make it obscene just because it involves two boys or two girls.”

Advocates for queer youth say making materials available that showcase LGBTQIA+ characters in typical teenage settings and situations is important. Everything doesn’t have to be about coming out or facing hardship for being gay.

“We have a really big collection—both fiction and nonfiction—where we can celebrate and see LGBTQ stories that are not just struggle stories,” says Sainato, who co-chairs her school’s GSA. “They’re like, ‘Here’s a rom-com, and it just so happens to have two boys in it, and that’s OK, and that’s normal.’ ”

An inclusive mindset

Librarians who go out of their way to make sure LGBTQIA+ students feel welcome say their work goes beyond having materials that represent the community. It’s about normalizing asking students for their pronouns and what they would like to be called while remembering their dead names, which are a part of their official school records.

Tamie Williams is the librarian at Neosho Junior High in Neosho, MO, a small rural community in the southwestern part of the state. For her, supporting queer students took on more urgency when her son, Alex, came out to her in his first year of college.

“It was heartbreaking,” says Williams. “My sorrow came from him not feeling comfortable telling me and worrying about not being accepted, and even worrying to the point that I would kick him out of the house. Immediately, my heart broke, and then to repair it, I made it my mission to make sure that I help students understand that they’re accepted, and that I love them.”

In today’s political climate, supporting LGBTQIA+ kids can require a bit of a juggling act. Some students are out at school but not at home. Others aren’t out in front of all of their classmates, but they have trusted a few educators with their identities.

“A lot of times students don’t want anyone else to know, like, this is my preferred name, that please don’t call me this in front of my parents, and I just respect that,” Williams says.

LGBTQIA+ in elementary school

Things can get even dicier when students are in elementary school. In March, DeSantis signed what critics have dubbed the “Don’t Say Gay” bill into law. It prohibits classroom instruction on sexual orientation or gender identity for students in kindergarten through third grade as well as instruction for any student “that is not age-appropriate or developmentally appropriate for students in accordance with state standards.” Similar bills are under consideration in several other states, including Alabama, Missouri, and Tennessee.

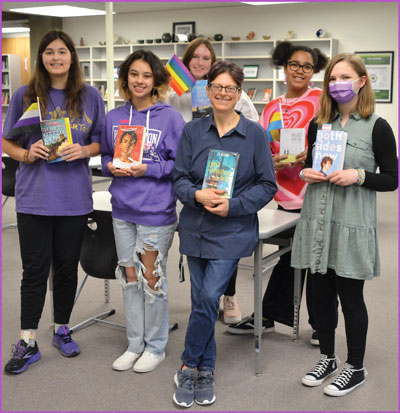

Rebecca Marcum Parker is a school librarian who splits her time between James Elementary and Garfield Elementary in Kansas City, MO.

“I never really entertained the thought that I would have students who are LGBTQ+ in elementary,” says Parker.

But that all changed when one of her fourth grade students came out as transgender about six years ago.

“It was like, ‘Well, that makes sense because I think you have a really good feeling about any persuasion you might have at a young age,’ and I knew that making all students feel included is good for their self-esteem and their emotional well-being,” says Parker. “And so, I always made sure that the library was a place that any students could come at any time with permission.”

Parker has been a school librarian for the past 24 years and says she supports her queer students by having an open-door policy and sharing resources on her walls such as hotlines for LGBTQIA+ youth. When she demonstrates how to put a hold on a book, she uses a title that explores gay themes just so students who are LGBTQIA+ feel affirmed and know that she has their backs.

“We just need to make clear with every action we can that everyone’s welcome and supported and belongs in the library,” says Parker.

Encouraging activism

For some school librarians, that means encouraging students to speak out about anti-LGBTQIA+ legislation. This year students in Sainato’s Project Lit book club have spent a lot of time reaching out to lawmakers.

“I am teaching our students how to find their legislators,” says Sainato. “We are writing letters to them, and we are sending them.”

Sainato encourages all of her students to register to vote once they’re eligible and points to bills that were delayed following their actions as proof that student voices matter.

Some supporters of LGBTQIA+ students say legislation meant to marginalize this community even further is having the opposite effect.

“I haven’t seen it make them sad,” says Long. “For specific students, it has made them grow, and by that I mean, they have become empowered to speak out, to use their voice. They’ve become more free in expressing who they are.”

In some schools, freedom of expression like that is encouraged all the time. At Charles Wright Academy, a private suburban school in Tacoma, WA, there’s a queer inclusion statement and affinity groups to make students in the LGBTQIA+ community feel less alone.

“It means that wherever they are in their journey, they know this is a place where they’ll be seen for their authentic selves,” says Sam Harris, a queer woman who serves as the school’s library director and one of the advisers for the campus GSA. “Libraries and books were a place years ago that I know I went to first when I was trying to figure out who I was, and students still do that today.”

Although Washington isn’t seen as a state that’s hostile to LGBTQIA+ people, Harris says lately she’s had to spend more time talking to students about the things they see in the news about anti-LGBTQIA+ legislation.

“They don’t always have the full picture,” says Harris. “Some of it is really allaying fears that, for example, what might be happening in Florida, or Texas, or Idaho, [doesn’t] impact Washington State.”

Today, Savella has come a long way from the quiet kid who arrived in Tennessee as a high school sophomore. He works as a gate agent for American Airlines and dreams of becoming a flight attendant. He doesn’t have any trouble expressing himself and speaking out about things he feels are unfair to the LGBTQIA+ community, and he attributes a lot of that to his school librarian.

“Having a Ms. Sainato in your life is so important,” says Savella. “When someone says you need to find your people, that’s a very important and valid point to make in your life. Because you need to find the right people, and you need to find the right supporters.”

Marva Hinton is a freelance journalist, a contributing editor at Edutopia, and the host of the “ReadMore” podcast.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!