Awesome Author Visits

For these authors, visits to school libraries are all about the interaction with students.

|

Westwood Elementary School students with author Miranda Paul and Isatou Ceesay, the subject of her book (back right and left).Photo courtesy of Jennifer Zurawski |

Inspiring, life-changing, thrilling, hilarious, emotional. In some combination, those are the types of experiences all school librarians aim for when they host an author at their school.

Increasingly, they also want interaction. It’s as much about the conversation as the presentation.

For a generation of young people accustomed to constant virtual banter, more authors are turning to games, workshopping kids’ stories, and student-centered activities to forge connections and make a lasting impact.

|

Author Miranda PaulPhoto courtesy of Jennifer Zurawski |

“Interactive author visits are immeasurably better experiences for everyone,” says Michele Bacon, author of the YA novels Life Before and Antipodes. “Workshops are inherently cooperative, but author talks—‘How an Idea Becomes a Book’—can be too much author chatter.”

Tracey Hecht, author of the middle grade “Nocturnals” series, currently engages in three to four virtual visits with students per month, in addition to in-person appearances. “It’s one of my favorite things to talk to kids about what they’re reading, what I’ve written, what they like in terms of literature and storytelling,” she says. Hecht also sees these conversations as opportunities to talk to kids about how their ideas could tie into writing projects.

The most inspiring visitors often use a range of strategies—including improv, surprise guests, and selfie opportunities—to create that memorable experience.

“The kids had to remind me to read the story,” says author Baptiste Paul of a recent school visit during which he demonstrated soccer tricks and talked about his childhood playing soccer in Saint Lucia, barefoot, just like the characters in his book The Field.

“We were all in tears,” recalls Jennifer Zurawski, library media and instructional technology Specialist at Westwood Elementary School (WES) in De Pere, WI, about a visit from writer Miranda Paul. It featured an appearance by Isatou Ceesay, the star of Paul’s nonfiction picture book, One Plastic Bag, about a grassroots recycling movement in Gambia.

Virtual connections can be just as meaningful as in-person events for today’s kids used to connecting with others online. “This is this generation’s form of interaction,” says Hecht. “They FaceTime each other while walking down the street...they’re so comfortable.” Moreover, virtual connections are an affordable option for schools with tight budgets.

|

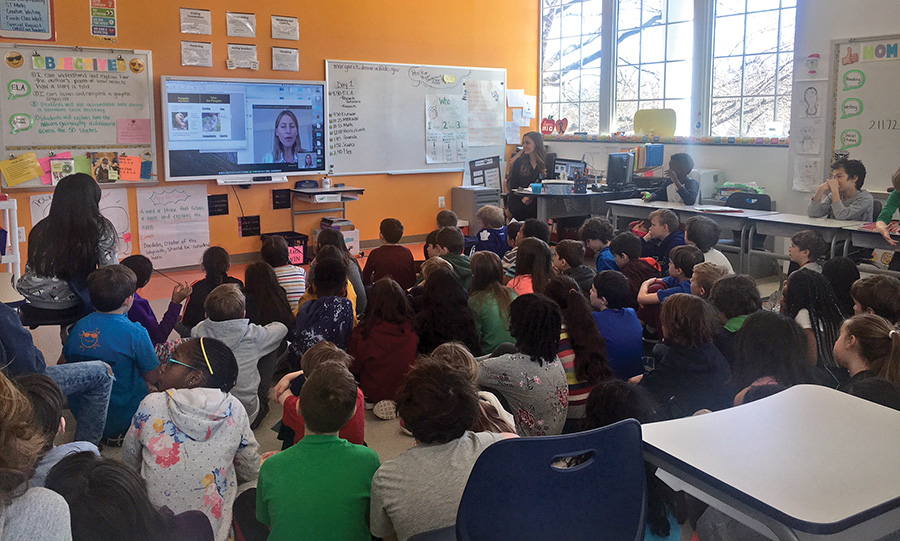

Tracey Hecht, on screen, virtually visits fourth graders at Lafayette Elementary School in Washington DC. Bailey Carr, who narrated one of Hecht’s audiobooks, visited students in person at the same time. |

Make it personal

Often, the kids who stand to benefit the most from author visits are those who have never displayed an interest in writing. Understanding the process of book creation may be a revelation for students who had never considered telling their own stories.

Bacon conducts lively story workshops for grades five and up. These often take the form of interactive improv sessions, in which she casts everyone in the class as a character in the book publishing drama: author, bookseller, critique group, agent, and editor.

“They bring their own personality to it,” Bacon says. Some students playing critique group members act more supportive than others; a child playing an agent may reject an idea outright, while another may request to see a whole manuscript.

Bacon’s message for students is that “your voice is unique, and only you can tell your story.” She gives tips about honing a narrative with character development, plotting, and more.

Paul arranged the surprise appearance by Ceesay, the Gambian environmental activist and main character in One Plastic Bag, at WES. Students were inspired by the story of Ceesay’s efforts to encourage recycling in her Gambian community—and further moved by meeting the woman behind the movement. The book—and visit—emphasized that everyone has a story worth telling, and how a small action, on the other side of the world from their own classroom, can grow into a global movement.

|

Baptiste Paul, author of "The Field," engages young students.Photo courtesy of Baptiste Paul |

Can’t afford a visit? Ask anyway

Librarians who lack funds for an in-person visit often still have options. Some authors will bundle visits to economically disadvantaged schools and libraries into a trip to a nearby event. “I keep a spreadsheet,” Bacon says. If she is already planning a personal trip or one that is funded, she can often spend a few hours visiting a nearby school for no fee. Other authors will reduce their fee in exchange for permission to sell books at an event.

Educators can find out about book tour listings by subscribing to author newsletters or following writers on Twitter or other social media. Cicely Lewis, librarian at Meadowcreek High School in Norcross, GA, hosted Dear Martin author Nic Stone after reaching out directly to her on Twitter.

Danielle Yadao, author visit manager for the Scholastic Author Visit Program, points out that publishers coordinating a book tour may be able to facilitate connections based on location or interest—but they can’t do it unless they are aware of a local need and interest.

Assembling funds from a variety of sources for a visit is another strategy. Angie Gaul, coordinator of the Authors in Schools program for Anderson’s Bookshops in Illinois, suggests reaching out to local businesses to sponsor an appearance or offering an author appearance as an “in-house field trip” option to PTOs or other funding organizations seeking to sponsor activities. If several schools in an area pool their funds to share the cost of travel expenses, a visit can be much more affordable and become a community-wide event.

Involve the community

Just as schools often host local professionals for a career day, hosting local writers spotlights authors as valuable community members. Professional networks such as the local branch of the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators can identify local writers who may be a good fit for a school.

Zurawski makes an author visit the culminating event of Author Fest, a school-wide celebration of the written word built into the elementary curriculum. Parents attend this after-hours event featuring the writer and showcasing books that the students plan, write, edit, and illustrate. Students can have their works read by or signed by the guest writer.

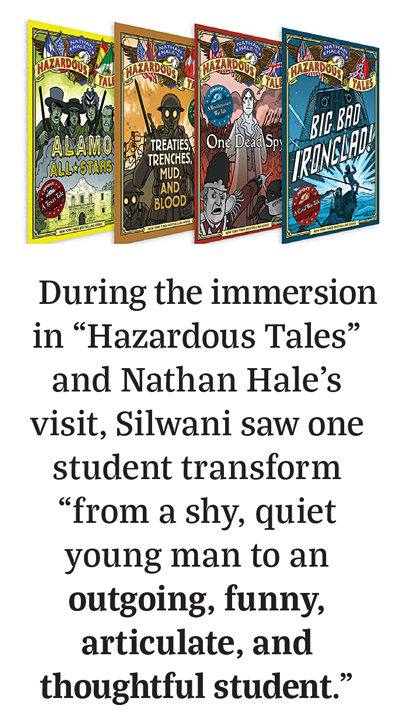

When Kelly Silwani, teacher librarian at Olentangy Orange Middle School in Lewis Center, OH, hosted Nathan Hale, author of several nonfiction works about American history in graphic format, the visit capped off a yearlong study of graphic novels across the middle school curriculum.

“I was asked by a social studies teacher to teach graphic novels to her class. I knew I could do it, but I wasn’t an expert,” she says. Silwani met a graduate student at Ohio State University who was focusing on literacy using graphic novels. She asked the student, Ashley Dallacqua, now an assistant professor at the University of New Mexico, to come to the class to teach—and invited her back closer to Hale’s visit.

“She worked with all content areas, helping [teachers] use Nathan Hale’s novels to support their content standards,” Silwani says. “When it came time for his visit, every student could make a connection to Nathan’s books.”

Over the course of the immersion in Hales’s “Hazardous Tales” series and the visit, Silwani saw one student transform “from a shy, quiet young man to an outgoing, funny, articulate, and thoughtful student—all because of the connections he made to others in his class who liked graphic novels and to the graphic novels themselves.”

Students value being involved in a visit as well. Giving them the opportunity to earn a role on a “hosting team” that escorts an author from room to room, greets them at the front door, takes photographs, or reads their introduction, can turn a visit into a classroom or grade-level project.

|

Ceesay (left) with students.Photo courtesy of Jennifer Zurawski |

High-impact virtual visits

In addition to “Skyping in,” Google Hangouts, Google Classroom, and Facebook Live are popular platforms for author connections. Regardless of the tech, a virtual visit is a simple way to strengthen connections to content and themes. Some authors will offer a brief visit at no cost when their books are used in classroom curricula.

These visits can be especially meaningful for authors. “It feels important to me,” Hecht says. “At big fancy schools, they pay you to come. But the people I meet virtually, they don’t get that kind of exposure, and we all know when it comes to reading, having more engagement and more engagement points at earlier stages in your life, is really valuable.”

“You get very distinct, amazing interactions with readers,” adds Hecht, whose novel Mysterious Abductions has been used as a One School, One Book title and comes with standardized curriculum guides. “You might [be connecting with] a library, and it might be storming, and only four kids show up. You really talk to these kids for a half hour in a demographic and part of the country you probably wouldn’t see. So I think the variation of virtual visits as a writer is really satisfying. I love it.”

These virtual connections also offer flexibility—for authors and educators. “The cost thing is the big one, but it’s also time,” says Hecht. “It takes three days to do an author visit….If I do an in-person visit, that’s a few days where I’m not writing.”

Old-school communication can also foster strong engagement—and a rewarding experience for today’s tech-immersed students. Handwritten letters to authors, or to pen pals at schools reading the same book or hosting the same author, can feel personal and intimate. Autographed bookmarks or adhesive book plates from an author provide a low-cost, high-impact way for each student to retain a one-on-one connection to the author and the book.

Heather Booth is head of teen and tween services at the Thomas Ford Memorial Library in Western Springs, IL.

Heather Booth is head of teen and tween services at the Thomas Ford Memorial Library in Western Springs, IL.

Virtual Visits Five Tips

Read the book! Be sure students have access to the title being discussed—and ample time to read it. Build in time for reading during class. Contact the publisher, your book distributor, or local bookstore to inquire about discounted copies for an all-class read. Prepare students. Tech-savvy though they may be, it’s important to go over basic virtual visit etiquette. Remind students that the author will be able to hear the classroom noise and see the activity, and set ground rules about how and when to ask questions. Do a trial run. Seeing the software you’ve chosen in action will help students understand the mechanics of how the visit will work. This can also help iron out any tech quirks that could derail the real visit. Set up a virtual visit with another classroom, or invite another teacher or parent volunteer to call in using the same setup you plan to use with the author. Send questions ahead. Make good use of the time by sending the author/illustrator the student questions beforehand. Your presenter can work answers into the presentation or bundle similar questions to answer at the same time. This also gives the author an idea of the tone and interests of the class. Follow up. Including a debrief activity afterward will help students connect their reading and the author visit in a meaningful way. Inquire ahead of time if the author has any suggested activities or exercises to use in conjunction with their appearance. Check the author or publisher website for discussion questions, curriculum support materials, or other supplemental activities that can work toward helping students integrate their experience. |

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Even a brief, 15-minute virtual conversation requires planning and preparation to be successful. Make the most of your connection with these suggestions.

Even a brief, 15-minute virtual conversation requires planning and preparation to be successful. Make the most of your connection with these suggestions.

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!