School Libraries 2021: Small Town, Big Job

In rural districts, school librarians can wear multiple hats, including that of public librarian.

|

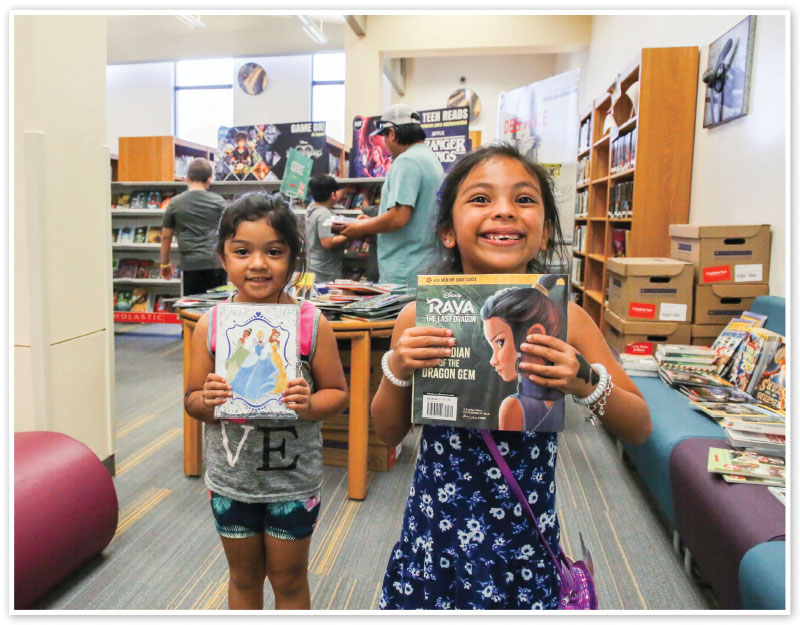

Kids with selections from the Crandall-Combine Community Library, co-located with the Crandall High School library. Kasie Valdez Hodges runs both.Photos courtesy of Kasie Valdez Hodges |

|

SPECIAL REPORT A Pandemic Tale in Pictures |

Kasie Valdez Hodges started her job as librarian for Crandall (TX) High School (CHS) and Crandall-Combine Community Library on July 1, 2020. Starting any position in the middle of the pandemic was no easy task, but Hodges had an even more challenging situation. She was moving from the elementary school to the high school and taking over the dual position of school and public librarian in the shared space.

It didn’t take long before she had to figure out how to advocate for both. The school wanted the library closed to public patrons to keep the students safe from COVID-19 as they returned in-person for the 2020–21 school year. But the public library patrons wanted access.

“How do I keep my students safe and using the library? But then also, how do I keep my public coming in?” she asked herself, noting that during the pandemic, community members who hadn’t read in years started checking out books. The library became a big part of their lives, and she didn’t want to lose that.

The solution was creative scheduling and a taxing workload for Hodges, who had two part-time assistants. She created curbside service for the public during school hours and would open the library for patrons when school was out. She was also managing the virtual library for students who chose to learn remotely.

It is not uncommon for school librarians in rural and small communities to also be the public librarian, according to Partners for Education, which oversees a rural libraries initiative. Heading up the school and public library in one location, Hodges’ goal is to create a seamless culture of reading in school and community.

Nationally, less than 40 percent of rural public school students meet reading achievement levels by fourth grade, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. In Crandall, 50 percent of district students are at proficiency level in reading, according to Public School Review. The level for high school students is 58.

According to the SLIDE report, smaller and rural districts were more likely to have no librarian than larger and suburban districts. But the data doesn’t show if that librarian is working in multiple schools or also a public librarian.

Some might debate calling Crandall, which is only about 25 miles outside of Dallas, “rural.” The Institute of Museum and Library Services defines rural as someplace outside of a high density population area. That would describe Crandall, but it might not for very much longer, as people keep moving into the district. Wendy Eldredge, superintendent of Crandall Independent School District, says Crandall is “rural moving towards suburban.”

A “fast-growth” area, Eldredge calls it. It seems an understatement. The district has added 753 students since last year. The increase has created new challenges for Hodges, but also enabled her to get a little more help. The district changed one of the part-time library aide positions to full-time and bilingual. The aide helps on the school and public sides and communicates with the growing Latinx population, which is using the public library more, according to Hodges. They are some of the many new residents seeking services and programming.

“Many new patrons are moving from areas in which their city library was a huge part of their everyday lives, so we are seeing patrons wanting more programming to fit their age ranges and interests,” she says. “One of the challenges is ensuring that we provide for our public patrons, but also maintaining the time to serve our student body. One way we are meeting this challenge is offering events that can serve both at the same time.”

|

Over the summer, Hodges ran STEM programs and special events, including bringing in a balloon animal maker. She also reorganized the collection to make selections easier. |

Eldredge, who also serves on the public library board, says it takes the right person to make everyone “feel special” and prioritized.

Increasingly, the library is filled with students and other young patrons working on projects and using new technology. Community members are having to adjust, Eldridge says. “We don’t want to lose that sense of the [public] library with all the changing dynamics of student growth.”

Hodges tries to spend an equal amount of time on both students and patrons.

During the school year, she visits classrooms to teach about the library’s resources, helps with research projects, and works with the community college library on a dual credit English class. She is also creating a library for the school’s alternative learning campus and teaches classes there.

Over the summer, she focuses on public programming for all ages. Along with a summer reading challenge this year, she ran STEM programs, story times, esports, and special events.

Samantha Lopez has two sons, 11 and 6, who loved the summer programs.

“It was fun for them, and they learned,” says Lopez, who also notes that the way Hodges has organized the books makes it easier for her sons to find what they’re looking for and that, overall, the library is very “welcoming.”

In addition to the kids’ programs, Hodges started an adult book club, and she hopes to put together a student library advisory group to work with the public board.

When school is in session, she and her assistants must monitor the doors for safety. There are two entrances to the library—one from the outside for the public and the other from the school for the students. While the public can’t get into the school building, they still must be buzzed into the public building during school hours, and students must be buzzed back into the school when they are done in the library. The process has become more time-consuming as student traffic to the library increases.

“She’s getting more and more kids in there,” says CHS principal Jared Miller, who came to the school at the same time as Hodges. “We also use the library at lunch for some of our [students] that don’t really like the big crowds at lunch. And we’re seeing more and more kids go to just read, hang out, and be in a quieter space.”

|

Hodges, second from right, with the Crandall High School team, which won the

|

Before coming to CHS, Hodges spent three years in the district as an elementary school librarian and, previously, an elementary classroom teacher. As part of her effort to get more high schoolers into the library and wanting to read, she brought the Battle of the Books from the elementary to the secondary level.

“Most of what she does is to draw kids in, whether it’s high school kids or the little kids from the community,” says Miller.

Hodges says she loves being able to serve all ages, but keeping up on so many new releases can be “a bit overwhelming.” When it comes to book recommendations and knowing the available material, she can no longer focus on just one age of reader.

“I’m constantly reading now,” she says. “I’m just trying to make sure I hit every age level.”

Just when she felt like the public library was up and running well after the COVID-19 disruptions, Hodges was faced with another obstacle. A deadly snow and ice storm knocked out power for days in the community, where buildings weren’t made to withstand such cold temperatures. When school pipes burst, the library flooded. While no books were damaged, the carpet needed to be replaced and the collection had to be removed during renovations.

“We still continued to check out books to our patrons using curbside service and to our student body using what we call ‘Book Dash’ to deliver books directly to their English classrooms,” says Hodges, who noted the help of a “healthy collection” of ebooks.

The library reopened a few weeks before school finished for the year. Through it all, DeAnna Thompson Smith, the Trinity Valley Community College librarian who collaborates with Hodges on the dual credit program, watched Hodges tackle every challenge.

“Kasie just takes it on full force, whatever it is,” says Thompson Smith, who notes that Hodges is getting on-the-job training for many aspects of the public library position, as her MLIS schooling was on a school librarian track. But, so far, she seems unfazed. “Whatever she needs to do to make it happen for both communities—it’s just, ‘What do we need to do? What do we need to rearrange?’ She’s just so positive.”

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!