Reading to the Rescue: Educators Use Time-Tested Strategies to Boost Literacy, Scores

Schools respond to the dip in reading scores with more tutoring and summer school programs; new reading curriculum; additional co-teachers and reading specialists in the classroom.

|

Illustration by James Steinberg |

Let’s get the bad news out of the way quickly. Kids are reading less today, and their standardized test scores are showing it. The percentage of children who say they “never or hardly ever” read for fun has increased since the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) started tracking this question annually since 1984. In the most recent assessment, 16 percent of nine-year-olds and 29 percent of 13-year-olds said they rarely, if ever, read for fun. The NAEP’s long-term trending results showed that nine-year-olds’ average scores in reading declined five percent, the largest drop since 1990. And in NAEP’s annual reading tests, scores decreased by three percent for both fourth and eighth graders.

COVID-19, remote learning, masks, smartphones, video games, and multitasking parents have all been blamed for the dip.

Kym Kramer, Indiana University’s director of school library media education, says librarians noticed a shift in how elementary students behaved when in-person learning restarted. They couldn’t concentrate long enough to receive short direct instruction for a project, she says. So, it follows that they’re also reading less.

No matter the cause, the effect is the same: school officials, teachers, and librarians are now tasked not only with trying to stem reading regression but with finding ways to reverse the trend.

The good news is that given record amounts of federal investment in education and the creativity of school officials and librarians, there is no shortage of solutions unfurling around the country. Schools are adding research-backed tutoring methods, expanding summer school programs, and extending the learning day. In more longer-term solutions, some schools are changing their reading curriculum while others are adding co-teachers and reading specialists to classrooms.

“It’s no one’s fault,” Kramer says. “We’re just trying to deal with reality.”

Making summer school the norm

Andrew Maxey, director of strategic initiatives at Tuscaloosa City (AL) Schools, has another take on today’s circumstances.

“I basically reject the narrative that students are behind. Behind what or whom? We weren’t keeping score the last time we had a global pandemic,” he says. “Let’s rewind 36 months. Very few people were bragging about where scores were then. It’s not a new thing, but it does create an urgency.”

For about five years, Maxey and Tuscaloosa City Schools have been running a summer program that aims to stem summer learning loss. The idea is simple: if students don’t regress over the summer, teachers don’t need to spend weeks remediating them in the fall.

The full-day program tacks the month of June onto the school year and is free to students. Maxey says of students who attended at least 15 days, 75 percent showed no regression from the spring. While the program began pre-pandemic, Maxey says federal ESSER funds are allowing the district to expand the program to serve more students.

Right now, about half of the district’s K–3 students attend. Tuscaloosa is trying to “normalize summer learning,” Maxey says.

“Our community has bought into this program. Tuscaloosa City is a case study in support of summer-learning strategies,” he adds.

Even with the goal of simply avoiding learning loss, Maxey admits that most students are doing even better than that. Many gained about a month’s worth of progress, he says, noting, “We could see it in the beginning-of-year data.”

|

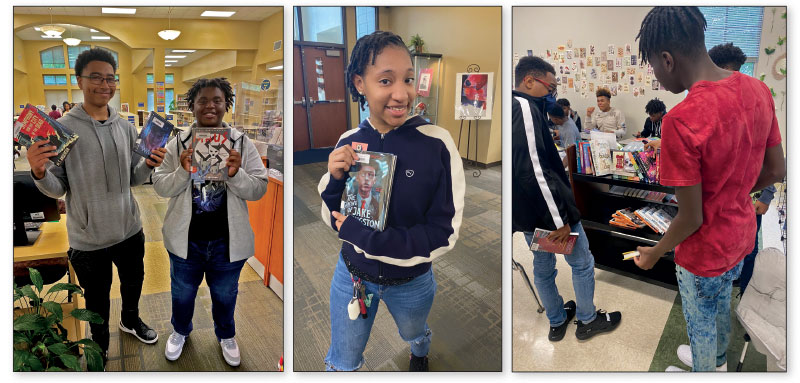

Left and center: Paul W. Bryant High School students with free-choice reading selections.Right: Bryant students take part in a book giveaway.Photos by Shelley Dorrill |

All in on tutoring

One of the most proven ways to accelerate children’s learning is through what’s called high-dosage/low-ratio tutoring. This is where students meet with a tutor for at least an hour a week in groups of three learners per teacher. A synthesis of research by Brown University’s Annenberg Institute for School Reform shows that students can gain the equivalent up of to 10 months’ learning by participating in a 12-week program.

Many states are using ESSER money to launch tutoring programs. Beginning in the 2020–21 school year through summer 2024, Tennessee is spending $200 million on a three-year tutoring program that aims to serve 150,000 students in math or reading in 79 districts.

The Tennessee Accelerating Literacy and Learning Corps targets elementary students who are just below proficiency in reading or math. Districts can run the program either during the school day or after school and pay tutors up to $50 an hour.

In Memphis, the 110,000-student Shelby County School District hopes to serve 7,000 students with 600 tutors in its 160 elementary schools. The district will target math in its first semester, before switching to reading, says Sean Page, the district’s chief of academic operations and school support.

While Shelby’s tutoring will happen during the school day, Rutherford County Schools’ program, over 200 miles away, will take place after school. This adds the extra hurdle of transporting children home after school hours, but allows the district to tap its interested teachers as tutors, says James Sullivan, the district’s assistant superintendent for curriculum and instruction.

Indiana rolled out a more modest $15-million tutoring program, Indiana Learns, in which parents of students who scored below proficiency in math and English can opt their child into tutoring. Parents can then choose their child’s tutors from a state-vetted list and pay with up to $750 in state funds as an alternative to private tutoring centers. More than 57,000 students statewide are eligible. The state’s commissioner of education, Katie Jenner, hopes to serve 15,000 students in the next two years.

One of the districts to sign on to the program before it started, the Metropolitan School District of Decatur Township, says it would retool its extended-day program to pivot to tutoring. Superintendent Matt Prusiecki acknowledges that allowing parents to choose tutors with state stipends is an unusual approach, but he believes his district staff’s knowledge of their students’ needs puts them in the best position to offer tutoring help.

Multiple approaches

While Tennessee is putting nearly all its chips into its tutoring program, other districts and states are diversifying ways to help improve children’s reading skills.

Besides Indiana’s statewide tutoring program, for example, the state has also earmarked $111 million to support students’ literacy development. The funds, which are the state’s largest ever financial investment in literacy, will enable schools to deploy instructional coaches for teachers, introduce professional development on the science of reading, and open a literacy center focused on the science of reading strategies.

“In Indiana, too many of our students are concluding third grade without foundational reading skills,” Jenner says. “Fewer still have the reading skills necessary for long-term academic success. As a state, we must lean in to urgently and intentionally address this challenge.”

Los Angeles Unified School District’s (LAUSD) superintendent, Alberto M. Carvalho, credits several programs with bolstering the district’s reading recovery in an editorial published in the LA School Report. All Families Connected provides hotspots and high-speed internet access to family homes to reduce the digital divide and provide equitable access to connectivity.

“We’ve increased instructional time through programs like Acceleration Days, which adds four optional days to the school calendar for teachers to work with students who need additional support,” he adds.

Another focus is on addressing chronic absenteeism, since students’ reading skills can’t increase if they’re not even making it through the schools’ doors. LAUSD enlisted hundreds of volunteers across the district to make thousands of home visits to help students who confronted challenges that inhibited their regular attendance the past year.

“Our iAttend initiative has successfully identified reasons for student chronic absenteeism, implemented responses and, just within the past year, decreased chronic absenteeism [15-plus days absent] by five percent and increased excellent attendance [seven or fewer days absent] by three percent,” he says.

|

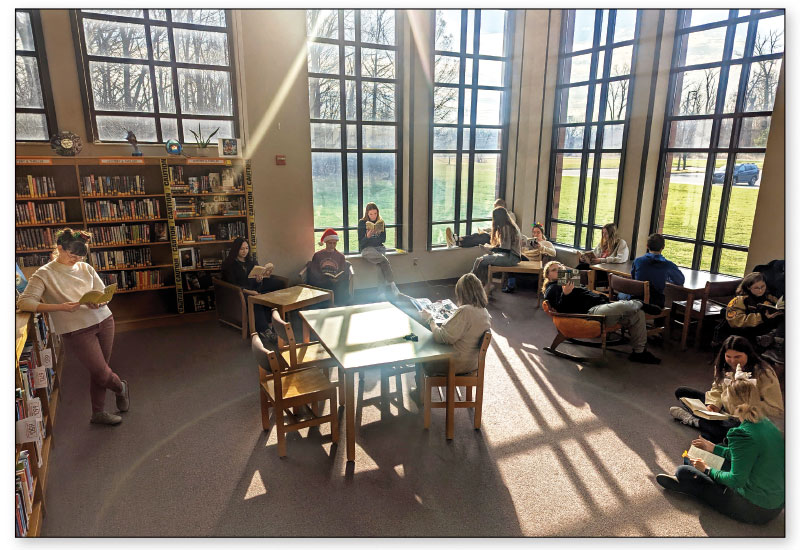

Chesterton High School students are allowed to choose their own materials for projects.Photo courtesy of Melissa Henrichs, Chesterton High School |

Back to basics

While poor test results and interrupted learning have pushed all these districts to create new programs, some schools and librarians are more comfortable embracing proven methods to spur learning, such as figuring out how to inspire kids to love reading for fun.

Kat Baxter, the librarian at Tuscaloosa’s Martin Luther King, Jr. Elementary School, says that’s her goal. “We focus on reading engagement,” she says, noting that too many students don’t have the stamina to read for even 10 minutes at a time.

Baxter says she’s found herself doing relaxation exercises with students, getting them to lie on the floor and listen to the sounds of the library to build their attention spans. When she talks to students about reading, she always reminds them to relax, breathe deeply, read to remember, and take notes. These principles will help them take standardized tests, she says. More importantly, she believes that creating a love of reading is a long-term investment in the students that will eventually result in stronger reading skills.

Across town at Paul W. Bryant High School, librarian Shelley Dorrill says she sees the same lack of reading stamina in her older students, adding that most are accustomed to, at most, reading a chapter in a book instead of an entire novel or nonfiction book.

One of the ways she addresses this is to ease students’ fear of book commitment; she tells them they are only taking new books on a date, not marrying them. Dorrill encourages them to stop reading a title that doesn’t engage them and choose another book, she adds.

Ensuring that the collection is filled with books that are representative of the young people entering your library is key. Dorrill, along with Maxey, has worked hard to bolster the school’s collection. Its 95 percent Black student body wasn’t big on fantasy until she and her co-librarian, Hillary Russell, added titles by writers of color to the section. Now, she says, “We can’t keep those books on the shelves.”

She has also implemented other tried-and-true methods to entice her readers, while encouraging them to engage with stories that are not quite on their radar.

One student fell in love with a graphic novel about Hurricane Katrina and started devouring other nonfiction graphic novels. At some point, he asked the Tuscaloosa high school librarian, “Does this mean I’m a reader?” She says, “I know that young man left our school realizing that reading is enjoyable.”

Emily Wilt, the library media specialist at Chesterton High School in Indiana, agrees with Dorrill’s assessments. “Students don’t know how to pick a book they will like enough to spend time with,” she says. Most of her high school juniors haven’t read a book in its entirety since fifth or sixth grade.

After the AP English class at her school finished its work for the College Board test last year, the teacher allowed the young people to visit the library and pick a book of their own choosing to read, Wilt says. In end-of-year feedback, she says multiple students thanked her, saying, “You allowed me to like reading again.”

These librarians are doing what librarians do best—trying to reach kids however they can.

In Wilt’s view, “Rather than new initiatives, at the secondary levels, we need to get back to basics.”

Dorrill says that with sharing students the power of a story helps remind them of the joy that reading can bring.

Wayne D’Orio has covered education for 10 years and writes frequently about education and equity.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!