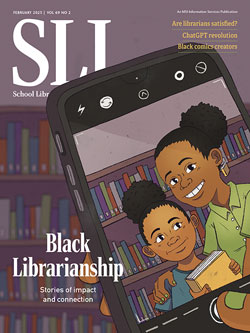

Black Librarianship: Stories of Impact and Connection

Greater representation serves young library users and the profession. But more effort is needed to bring in—and retain—Black librarians.

|

|

Illustration and SLJ February cover by Theodore Taylor III |

Realted article |

Eboni Henry works hard to make her library at Truesdell Elementary School in Washington, DC, more than a place for books. It is a welcoming space to take a break and feel supported. It is a place where so many of her students can see themselves in their librarian. And it is a place where they can feel seen and understood.

“For many of my students, a large part of their self-image is tied to their hair,” she says. “When it’s freshly braided, they feel good about themselves. But when the braids have been taken out, and they’re wearing an Afro puff, their self-esteem is low.”

To combat that drop in confidence, Henry wears the style herself many days.

“I often wear my own hair in that style and make a point to tell them how beautiful they are,” she says. “We take selfies in our puffs and call ourselves the Puff Gang. They look at me and feel like they’re ok when they see Ms. Henry’s got a puff, too.”

Representation and diversity are important, says Henry, but there is not a lot of it in her chosen field. Despite efforts to encourage more Black people to enter the profession, librarianship remains overwhelmingly white. The 2021 numbers from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics show that nearly 87 percent of librarians are white, while only 7 percent are Black. Leaders in the field identify several reasons for this disparity.

“People have more options,” says Carla Hayden, the Librarian of Congress and a former president of the American Library Association (ALA).

In 2016, Hayden, who holds a doctorate in library science from the University of Chicago, became the first woman and the first Black person to serve as Librarian of Congress. She points to the fact that librarianship remains largely a female-dominated field, and today women of all races have access to a wider variety of career paths.

“There weren’t that many options at certain times in our history, and once more fields opened up and there were more opportunities, people could go into other professions that paid better,” says Hayden.

In most states, being a school librarian requires a master’s degree, and the median salary of a librarian in the U.S. is about $61,000 a year. Former school librarian Erika Long says that need for the Master in Library and Information Science (MLIS) degree and lack of payoff makes it difficult for many to enter the field.

“I have to take on the cost of that continued education for graduate school,” she says. “For a lot of Black people, that is an issue. So how do you weigh the cost of pursuing additional certification or an additional degree, when you’re not going to receive the return on investment in the career?”

In an effort to diversify the field, ALA offers scholarships to people of color. The Spectrum Scholarship provides tuition assistance and funds for professional development. Many schools provide additional financial support to Spectrum scholars to help fully cover the costs of their education.

Shauntee Burns-Simpson took advantage of a similar program to become a librarian. Today, she is the associate director for the Center for Educators and Schools at the New York Public Library. Burns-Simpson is also the immediate past president of the Black Caucus of the American Library Association.

She praises scholarships and trainee programs like the one that paid for her to attend graduate school, but says more needs to be done in terms of retention.

“If you look at the numbers, it seems like we’re not really growing, but we’re recruiting librarians into the profession,” says Burns-Simpson. “They’re just not staying in the profession, unfortunately.”

The statistics bear that out. While Black librarians have never made up more than 10 percent of the profession, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, they were at 10 percent in 2011 and 2017 before dropping to the current level of 7 percent just a few years later.

Burnout is often mentioned as one of the reasons Black librarians leave the profession. In addition to the typical duties any librarian would have, Black librarians are often asked to head up diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts or to consistently work with the most challenging students in a school. These things combined with the relatively low pay make the job less attractive to many candidates.

“I’ve met and worked with so many amazing, smart, and talented individuals who have come into the profession with so much energy and passion for the work, and unfortunately, over time, they get burned out,” says Burns-Simpson. “If institutions aren’t supporting them, they start to feel less confident in what they’re bringing to the work.”

K.C. Boyd, librarian at Jefferson Middle School Academy in Washington, DC, and SLJ’s 2022 School Librarian of the Year, says there have been times when she didn’t feel supported by administrators at her school, and sometimes it was obvious they doubted her expertise.

“Some of our principals still have a mentality that a white librarian is what’s needed because they’re going to be the authority on the literature, and I’ve had this experience personally,” says Boyd, who adds that she has dealt with her share of microaggressions. “In 24 years, I’ve worked for some white and African American principals that second guessed my judgment [and] my schooling and oftentimes would seek a second or third opinion from an outside source instead of relying on me.”

In light of all of these challenges, what will it take to attract more Black librarians and keep them on the job? Experts in the field agree that there is no easy fix or one-size-fits-all solution. Hayden suggests that reframing the way the public looks at librarians would help. As a society living in the Information Age, the position should be celebrated.

“This is a profession that is dedicated to providing accurate information and checking sources,” says Hayden, who also wants to eliminate the stereotype of the meek librarian. “Our superpower, if you will, is empowering others.”

Getting young people to see the power of the librarian could inspire them to consider librarianship as a career.

“It would be great to see something that will go down into the elementary schools to say, you know, you, too, can be a school librarian,” says Boyd. “It’s a community-based career. You give back, and you support the people within your community. This position needs to be included, along with those other community-oriented careers, but it’s not promoted like that.”

Seventh grader Kara Ekeberg is part of the Shaker Heights (OH) Middle School junior librarians club. She has learned how to sort and repair books, helped with library fundraisers, and learned about being a librarian.

“I always thought a librarian was just sitting behind a desk, waiting for kids to come and check out books, but, really, it’s a whole lot more behind it. And, once I saw that, I was way more interested in it,” says Ekeberg, who is multiracial.

The shortage of Black librarians comes as schools are becoming more diverse. What does it mean when more schools are full of children of color, but this diversity isn’t reflected among the people who curate the collections in school libraries?

“We all know the importance of representation,” says Burns-Simpson. “We know what’s important when we talk about books or we’re talking about being in spaces and in careers, it just confirms belonging. It confirms that you can do it, too. It sends the message that the library is a place for you.”

Marva Hinton hosts the ReadMore podcast.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!