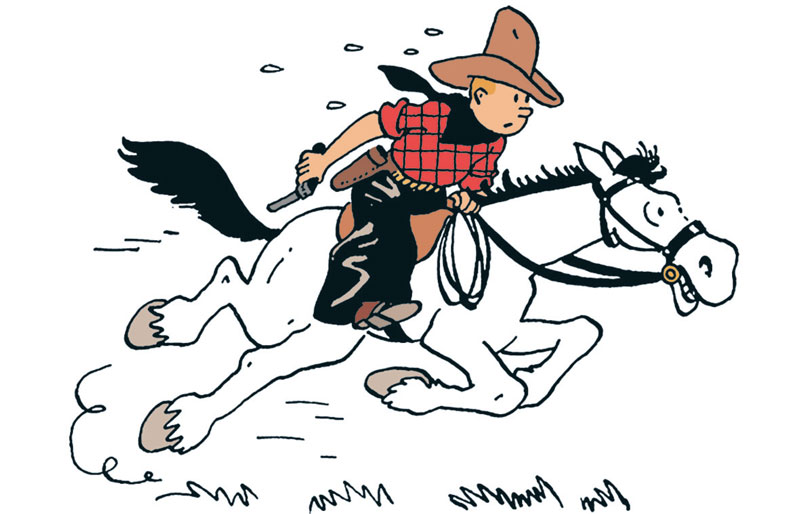

15 Franco-Belgian Comics That Go Beyond "Tintin"

It’s not surprising that with rising U.S. sales of middle grade graphic novels, publishers looked across the Atlantic for material to translate. They found, in France and Belgium, brightly colored children’s bandes dessinées.

|

© Hergé/Moulinsart - 2021 |

There was a time in America, from the 1980s through the late 2000s, when graphic novels were still a novelty and children’s comics were almost nonexistent. Meanwhile, in France and Belgium, brightly colored children’s bandes dessinées, or BDs, were available everywhere: in supermarkets, on newsstands, and even aboard French high-speed trains. So it’s not surprising that with rising U.S. sales of middle grade graphic novels, publishers looked across the Atlantic for material to translate.

Unlike manga, Franco-Belgian comics are not usually labeled as such, but they do have certain standard formats, which may or may not be preserved when they are imported. The most common format for Franco-Belgian comics is called the “album”: 48 pages, with a trim size of about 8 x 11 inches (larger than an American comic), with either a hard or sturdy paper cover. American publishers sometimes put two or more albums together to increase the page count. They also may shrink the page size to make the comic fit into a standard graphic novel format, which can cause a problem: If the lettering is too small, the comic may be hard to read. BDs are almost always in full color. And like American kids, French-speaking readers enjoy the familiar, so most of these graphic novels run in series, although the individual volumes may stand alone.

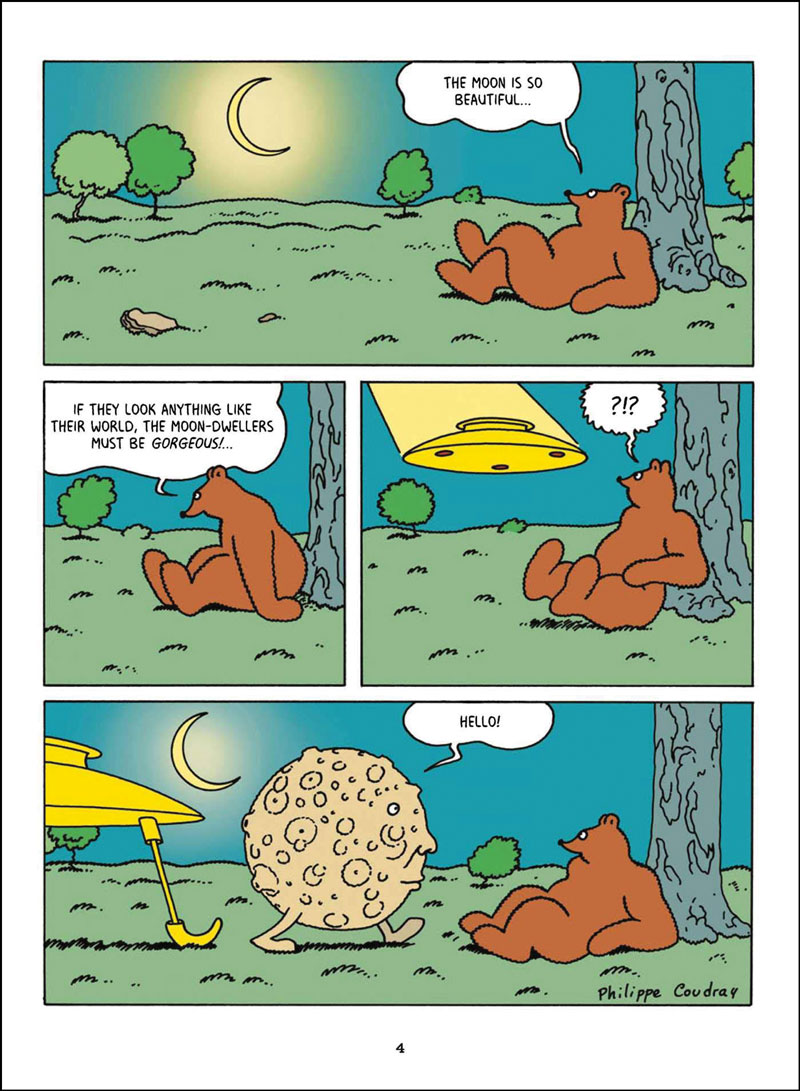

In terms of visuals, modern Franco-Belgian children’s comics have a wide variety of styles. Humor comics are often drawn in a cartoony, exaggerated style, even more so than American comics, while fantasy stories and serious dramas usually have a more realistic look, with lots of detail and watercolor-like coloring. One visual trope that new readers may find confusing is the use of borderless panels with amorphous shapes. Sometimes word balloons or text boxes are borderless as well.

|

“Bigby Bear” by Philippe Coudray |

The most popular children’s genre in English translation is slice-of-life comedies and gag comics, usually paced so that each page is a brief story, although the episodes may build up to an overarching plot. Young reader series such as “Bigby Bear” and “Billy & Buddy,” and middle grade series such as “The Sisters” and “Chloe” follow that formula, so the pacing makes them good picks for fans of “Big Nate,” “Phoebe and Her Unicorn,” or “Wallace the Brave.”

Other popular genres are middle grade drama, fantasy, and biography. These are comparable to American graphic novels in style and format. Because of the album format, the stories may be shorter, but the volumes themselves may be longer since publishers bundle two or more of the original albums into a single volume; this was done with Cici’s Journal and “Milo’s World.”

The “special sauce” these comics bring is that while they are relatable for American audiences, there’s also a whiff of the unfamiliar. Mark Waid, publisher of the French-American Humanoids, points to its series “Where Are You, Leopold?” as an example. “While their stories could take place in rural America, that they’re set in France gives them a slightly different flavor, from the way day-to-day life is portrayed to how kids (and people in general) look and dress,” he says. “That doesn’t change the stories, but if I were a kid reading these books, I’d come away a little more curious about the world and about different cultures.”

Of course, cultural differences can also pose a challenge for publishers. “We have to look for material with enough common touchstones that any cultural differences within the stories are intriguing rather than a barrier,” says Waid. “Humor’s a stumbling block sometimes; as you can imagine, with books dependent on verbal humor, not every joke translates, so there’s some rewriting that sometimes needs to be done, and capturing the gist of a joke in American English isn’t always easy.”

The most serious issue that arises with Franco-Belgian children’s comics is representation of non-white people and non-European cultures. Critics have called out stereotypes and inaccurate representation in “Tintin” and “Asterix,” and in the case of “Asterix,” the American publisher Papercutz has added an afterword by Black comics writer Alex Simmons that provides historical context for the comic and the setting. Stereotypes and inaccurate representation are more of a problem with older humor comics, and it’s best to take a look through these if possible; if not, the covers are often an indication of what’s inside. (Many BDs are available on digital library services such as Hoopla and Comics Plus, as well as ComiXology Unlimited.)

Waid says this has not been an issue so far with any Humanoids titles, either current or planned. “If and when it becomes relevant to us,” he says, “I imagine we’d approach such material very, very mindfully, knowing that it would have to be of exemplary quality, with messages for kids important and unique enough to outweigh any historical baggage that might need to be offloaded. I’m certainly not a fan of altering existing work without consulting the original author, so depending upon the age of the material, it might be out of bounds for us just based on whether or not the author’s even still active.”

On the other hand, many stories, especially newer ones, feature main characters of color or diverse supporting casts, reflecting the multicultural nature of modern Europe. These include Cici’s Journal and Marguerite Abouet’s series “Akissi,” based on the author’s childhood in the Ivory Coast. Women are still a minority of French comics creators (estimated at 27 percent in 2016), and people of color an even smaller proportion, although their numbers are increasing.

The American publishers who have included Franco-Belgian comics in their lineups include Dark Horse, First Second, HarperCollins, IDW, Lerner, Magnetic Press, Papercutz, and TOON Books. Humanoids has a children’s imprint called BiG that includes French and American comics, and Waid says they are working with the French publisher La Boîte à Bulles to begin publishing books simultaneously on both sides of the Atlantic. Cinebook produces a range of traditional genre stories, including sci-fi, adventure, and humor comics for kids and adults. Its books are always in the French format, with a sturdy soft cover, and titles include the long-running cowboy series “Lucky Luke” and the cheerful gag-a-day comic “Billy & Buddy.” Expanding the scope a bit, the digital comics service Europe Comics makes a wide range of European comics available via library services, Kindle, and other platforms. Occasionally an American publisher will pick up those comics for print, as happened recently with Chef Yasmina and the Potato Panic (First Second, 2021).

There’s no doubt that Franco-Belgian comics are here to stay. With their broad selection of humor, fantasy, and slice-of-life stories, as well as a long tradition of sequential art and an amazing array of creators, they have a lot to offer, whether readers recognize their origins or not.

Unbeatable BDsHere’s a look at some recent and notable Franco-Belgian comics for middle grade readers. This list reflects the current state of diversity in the French children’s comics industry and the choices that American publishers make as to what to bring over. Bonne lecture!

“Akissi” by Marguerite Abouet. illus. by Mathieu Sapin. Nobrow/Flying Eye, 2018-20. “The Ballad of Yaya” by Jean-Marie Omont & others. illus. by Golo Zhao. Magnetic Pr., 2019-20. “Bigby Bear” by Philippe Coudray. illus. by author. Humanoids/BiG, 2019-20. “Billy & Buddy” by Jean Roba. illus. by author. Cinebook, 2013-19. “Castle in the Stars” by Alex Alice. illus. by author. First Second, 2017-20. Catherine’s War by Julia Billet. illus. by Claire Fauvel. HarperAlley, 2020. Chef Yasmina and the Potato Panic by Wauter Mannaert. illus. by author. First Second, 2021.

“Chloe” by Greg Tessier. illus. by Amandine. Papercutz/Charmz, 2017-20. Cici’s Journal: Lost and Found by Joris Chamblain. illus. by Aurélie Neyet. First Second, July 2021. The Fly by Lewis Trondheim. illus. by author. Papercutz, July 2021. “Milo’s World” by Richard Marazano. illus. by Christophe Ferreira. Magnetic Pr., 2019-20. “The Sisters” by Christophe Cazenove. illus. by William Maury. Papercutz, 2016-21. “Where Are You, Leopold?” by Michel-Yves Schmitt. illus. by Vincent Caut. Humanoids/BiG, 2020-21. The Wolf in Underpants by Wilfrid Lupano. illus. by Mayana Itoïz & Paul Cauuet. Lerner, 2019. Young Leonardo by William Augel. illus. by author. Humanoids/BiG, Mar. 2021. |

Brigid Alverson is a writer and the editor of SLJ’s Good Comics for Kids blog (slj.com/goodcomics).

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!